A sabbatical provides time to heed Polonius’ advice to Laertes: “Give every man thine ear, but few thy voice.”

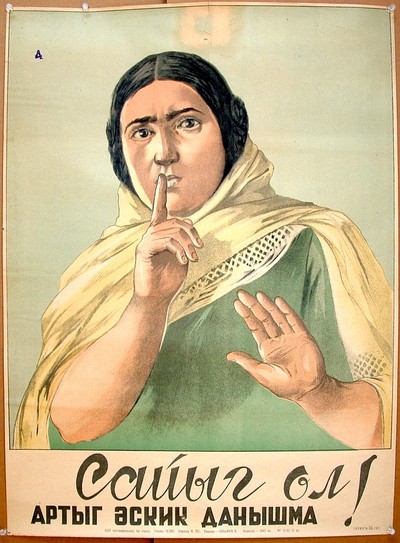

The instruction was probably a shop-worn platitude even in Shakespeare’s day. Still, it is sound advice. We should each keep it written somewhere in full view—taped to the cover of an iPad, perhaps, or the back of a smartphone. You can insert it into a cookbook, use it to mark your place in a missal, or pencil it on the lintel over a kitchen door.

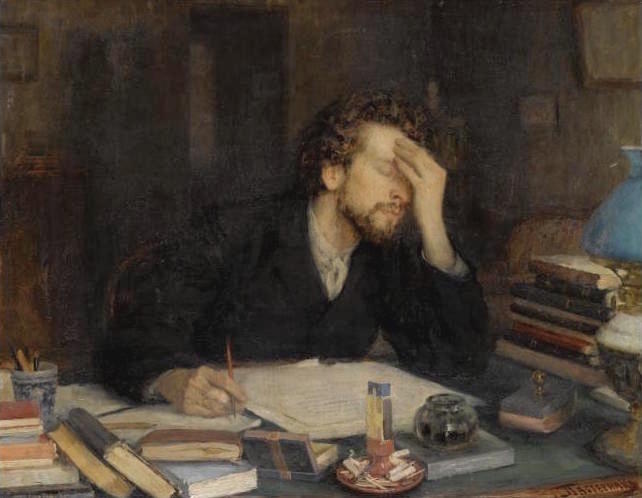

Writers should have it tattooed on the back of their hands.

Manhattan’s Park Avenue United Methodist Church delights in edifying passersby with a pithy saying. Some while ago it showcased Polonius’s counsel on the external bulletin board bolted to its façade. It startled me on my way up 86th Street toward the Metropolitan Museum. Those white block letters rampant on a black ground, and behind glass, seemed intended for me as surely as that bottle labeled “DRINK ME” was meant for Alice.

I took Polonius’ words to heart at the time, and have kept them close ever since. They remain a call to modesty, a stay against imagining that one’s own voice deserves a place in the hurly-burly or rises above the din.

We occupy a sound box. Daily life resonates with incessant news and opinions on relentless questions. Did Roy Moore do it? Will we ever be rid of Hillary? Are transgendered females better than real ones? Is an answer to the dubia in the end zone? How many feminists (jihadists? Russian hackers? NFL showboaters?) does it take to change a light bulb? So much web-surfing, tweeting, texting, emailing, Facebooking, and Instagramming. It is easy to mistake the buzz and clamor of it all for the fabric of ultimate reality.

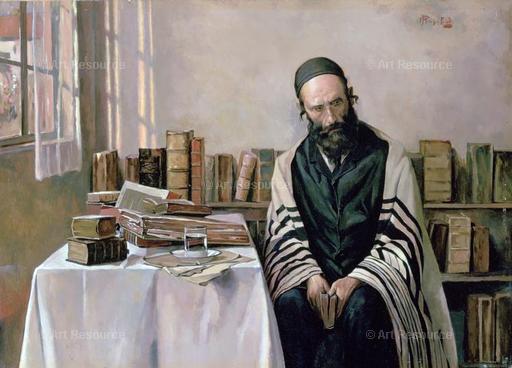

Soren Kierkegaard, theologian and shaper of modern minds, knew better. He never crossed the Tiber, though many who came under his influence did just that. It is hard to imagine Marshall McLuhan, a convert from Methodism, reflecting on religion and media without having been primed and seasoned by Kierkegaard’s The Present Age.

A foreglimpse of current media saturation, his book appeared in 1846, a full century and a half ahead of today’s communications onslaught: the cable news and online publications, an infinity of blogs, a relentless flow of commentary and counter-commentary. He wrote in advance of a wired world, before pod casts, instant messaging, chat rooms, and running screen shots of Twitter feeds. Yet The Present Age, so attuned to the penetrating thrust of media, bears upon our own time. In it, Kierkegaard identified “talkativeness” as a symptom of societal decline.

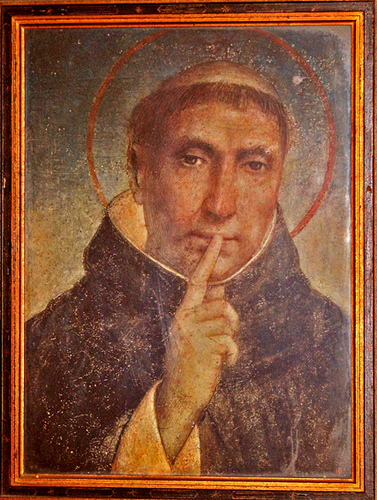

What is talkativeness? It is the result of doing away with the vital distinction between talking and keeping silent. Only some one who knows how to remain essentially silent can really talk–and act essentially. Silence is the essence of inwardness, of the inner life.

Kierkegaard’s definition embraces more than table talk or casual chatter. It runs the length of the media clothesline on which we hang our hearts, our aspirations, our biases, and judgments in public.

Talkativeness epitomizes the media world we inhabit. We have to work to thresh truth from canned narratives, the permanent from the passing. Surely words mattered more when, to write them, they had to be inscribed in moist clay and left carefully to dry in the sun.

A sabbatical is time to bake under a different sun. Time to honor accumulated obligations. Time to read. If Samuel Johnson was right—that it takes a whole library to make one book—then it can take a full shelf to make an essay earn its keep. Eliot’s words in Ash Wednesday, welcomed as prayer, plead for time: “Teach us to care and not to care. Teach us to sit still.” East Coker echoes the reflection: “I said to my soul, be still, and let the dark come upon you / which shall be the darkness of God.”

The psalmist said it first: “Be still, and know that I am God.”

• • • • •

It is hard to sit still for long. There comes a time to bestir. An impatient reader scolds me: “A still mouse gathers no cheese.” It was not cheese I was after. But I know what he means.

A.D. Sertillanges, O.P. said much the same in The Intellectual Life. Written a century ago, his text is a treasury of reflections on the spirit and methods of an intellectual vocation. It is a guidebook to what he called “the state of grace of the intellectual worker.”

He meant persons whose lives were devoted to letters: writers, scholars, disciples of the written word. Yet every thoughtful person—every sensitive reader—is an intellectual worker in some manner. No need to be certified or carry papers. And a writer is only a writer when she is writing. A sabbatical let me stop the clock on intervals for hanging out the line. Nevertheless, the ruses of sloth are endless, as Fr. Sertillanges noted. It is time, now, to get back to the page.

Perhaps we will get there together.