Earlier in the primary circus, Roger Kimball observed that Donald Trump’s vulgarity was the only authentic thing about him. It was a good line. And the perfect prologue to last week’s gleeful report that the Donald’s stockpile of historic paintings is as genuine as the color of his hair: “Trump’s Vast Art Collection Isn’t What It Seems.” Richard Johnson, writing in Page Six, snickers:

The French Impressionist paintings that decorate his homes are likely—don’t call them fakes—reproductions.

So! His paintings are worth no more than their glittery gilt frames! There you have it. All brass and bluster, Trump is a philistine to boot! Quite true. But in this instance, also quite beside the point.

Johnson’s sneer, too, is not what it seems. His use of the conditional is telling. Is it likely that a New York Post gossip columnist has a steady eye for the Real Thing? Even Bernard Berenson’s eye was off when it suited. And if timing matters, what Johnson calls “probably a skillfully painted copy” of Renoir’s La Loge in Melania’s office might well be genuine. The original sold at Sotheby’s for close to $10 million to an unidentified buyer in 2008. By then, Donald and Melania had been married three years. A Renoir would have been a lovely present for the current Trumpess.

And if Melania’s trophy is a facsimile, that still does not mean the Trumps do not own the original. Buyers of mega-buck art frequently do with artworks exactly what they do with jewelry—commission copies for display while they store the originals in vaults. Take the example of Nelson Rockefeller. That splendid large Miró in the living room of the family mansion in Kykuit is a copy. The real one is in an undisclosed warehouse.

Substituting an expert copy for the original is not uncommon for a host of reasons. Antiquities, for example, can be sheltered from pollution or erosion by replicas. The Michelangelo David that day-trippers admire in Florence’s Piazza della Signora is a replica. The original is inside the Accademia, safe from weather and vandals. So with the famous horses of St. Mark’s Basilica, Venice. The ancient originals were brought inside in the 1980s to protect them from corrosion. Outside are fiberglass doubles.

Problems raised by the difference between an original and an expert simulation are more metaphysical than aesthetic. A copy, particularly a fine one, offends against our modern cult of originality. It severs that mystical tie between the art and its maker. It sullies the devotional activity of art gazing. Among secular custodians of culture, the original object inspires a piety akin to religious veneration of sacred relics.

Jacques Barzun phrased it nicely: “Art is the gateway to the realm of the spirit for all those over whom the old religions have lost their hold.” It is a safe bet that Trumpsters are blasé about the redemptive claims of art.

Transfer of reverence from religious faith onto Art is a shift that growing numbers of people lack the privilege of making. There are substantial reasons to dread a Trump presidency. Immunity to the reliquary role of an original work of art is not one of them.

This last December in Vanity Fair, Mark Bowden sniffed at Trump’s indifference to art’s transcendental graces in favor of its merchandise value. Instead of slaking a thirst for the absolute, his paintings hang—surprise, surprise!—as profane status symbols:

He showed off the gilded interior of his plane—calling me over to inspect a Renoir on its walls, beckoning me to lean in closely to see . . . what? The luminosity of the brush strokes? The masterly use of color? No. The signature. “Worth $10 million,” he told me.

Oh, come on, Mark! It is no secret that high-level art dealing is very much a trade in signatures. Much of what passes as esthetic value hinges on the reputation of the signature, not necessarily on what meets the eye. A throwaway schmear on a paper napkin by a prestigious name is worth many multiples more than something substantial and lovely by an artist unknown on the resale circuit. The social role of art never has been purely aesthetic—not when Roman aristocrats collected Greek pieces, not in the Renaissance, and not now.

Bowden’s tut-tut in Vanity Fair flatters readers’ intellectual snobberies. It gives urban pretenders something to smirk about and amuses the cultural elites who contribute to the sense of dispossession that fuels fever for Trump. But a disenfranchised, disdained electorate has little taste or opportunity for art’s invitation to recollection in tranquility. A brash casino mogul after successive betrayals by the Better Sort? Why the hell not? The moral and civic vulgarity of our political class is more consequential, more dangerous, than Trump’s offenses against polite taste. His defenders see no reason to bypass a man who understands that painting—whatever else it might be—remains a portable species of real estate.

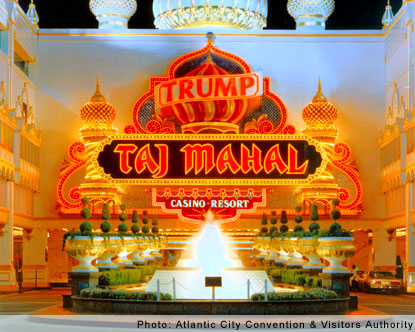

If Trump understands anything, it is real estate. Plus, he knows brands (Impressionism is a stable one) and how to build them. As evident in the TRUMP logo flaunted on the façade of every building he has ever piled on innocent properties, the man is exquisitely brand conscious. And in a culture of consumption, the label is all. Under its conditions, the impression made by a commodity—including a candidate-commodity—takes precedence over the reality of the commodity itself. Trump is the beau ideal of consumer culture.

Every election is a marketing campaign. While Trump’s candidacy can hardly be dismissed as an exercise in branding, it is plainly fueled by brand recognition. Edward Bernays, granddad of the public relations industry, would applaud. In 1928 he remarked that politics was “the first big industry in America” and recommended the application of modern marketing techniques to campaigns. Since then, the packaging and sale of candidates to voter-consumers has become so intrinsic to the electoral process that we barely recognize it for what it is. (Obama’s styrofoam Greek columns worked.)

![Donald Trump holds a ceremonial umbrella given to him during an announcement in downtown Vancouver, B.C. Wednesday, June 19, 2013. The Trumps were on Canada's west coast to announce the building of Trump International Hotel and Tower Vancouver. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jonathan Hayward ORG XMIT: JOHV105 ORG XMIT: POS1306191749352012 [PNG Merlin Archive]](https://studiomatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/11827537.jpg)

Thirty five years ago Abigail McCarthy lamented the influence of pollsters, boosters, image makers, focus groups—the entire social-science brood of persuaders—on elections. What she wrote then in Commonweal holds even stronger today: “Voting under such circumstances is not making a choice. It is buying a product.” All the consulting strategies driving consumer visions of the perfect vacuum cleaner work for candidates as well.

Product design sells. But the packaging on the Trump goods ripped open the instant he excused his gaffe on abortion by blurting: “Isn’t that what you people want to hear?” Pair that question—a confession, really—with poignant popular appeals to Trump’s supposed know-how: “He is a businessman. He knows how to get things done.”

Between them, the pathos of Trump’s candidacy comes close to unbearable.

Note: This essay appeared first in The Federalist under the title “Trump: The Art of the Brand.”