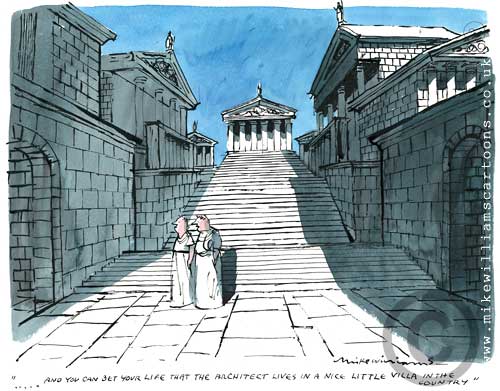

DISMAY OVER THE DISFIGUREMENT of an artist’s training by pretenses to metaphysical depth and invented meanings—call it skywriting—sent me to the library. What for? Not exactly sure. Anything to clear the palette, really. A good mystery would have done the job. But I had to pass down the architecture aisle to get to pulp fiction. John Silber’s Architecture of the Absurd caught my eye. So did its delicious subtitle: How “Genius” Disfigured a Practical Art.

It is a contentious book that earned Silber the title of Architecture Crank in 2007, the year it went to press. The son of an architect, Silber grew up immersed in the study, and physical construction, of buildings. Unlike garden variety architecture critics, he knows more than the history of architecture. He learned, at his father’s knee, the practical expectations and requirements needed by a responsible architect. He can read—and calculate—plans and specifications and can relate elevations and cross sections to floor plans. Silber has a handle on the humdrum details of such things as pouring concrete and setting plumbing. His involvement in both the design and construction of many campus buildings during his quarter-century tenure as President of Boston University earned him an honorary membership in the American Institute of Architects in 2002.

So, if he dismisses “elaborate, high-flown aesthetic justifications of design features as gratuitous bloviation,” he has a reasonable claim on our attention.

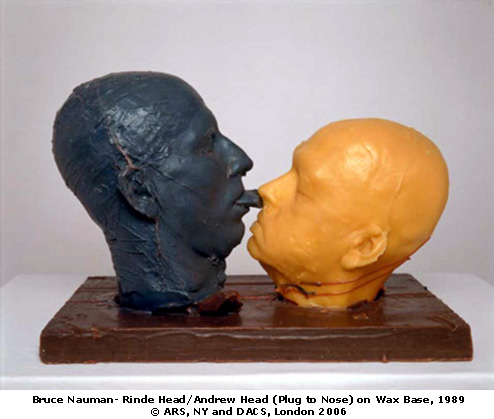

He had a particular claim on mine that day. Just before picking up his book, I had browsed an interview Robert Storr gave to The Art Newspaper, in October, 2009. The headline lifted the heart: “Most Theory Has Little Bearing on Art.” But so much for a copy editor’s catchy title. Storr served up the customary lux et veritas: “If you want to talk about Jasper Johns, if you want to talk about Bruce Nauman, you should read Wittgenstein.”

Marvelous comment, that. Notice the word “talk.” Talking and seeing are not the same. The first is a parlor game that grants the brass ring to the speaker who sounds like someone with a true theoretical mind. It is a game the blind can play. By making the statement, Storr offers himself, by means of insinuation, as a sterling example of the brainy art world conceptualist. Nothing suits a dean of Yale Art School like a flourish of Teutonic speculation.

It is just this sort of bogus philosophic exposition that Silber has small patience with. And his impatience, though a tad scattershot at times, is refreshing. He is not intimidated by reputations, testimonials or price tags. Daniel Libeskind, Philip Johnson, Frank Gehry and Harvard-credentialed Josep Lluis Sert each come in for a drubbing. Libeskind’s proposed new wing of the Victoria and Albert Museum, to cite just one, is described as a “barrage of intimidation, grounded in the false conflation of architecture and fine art.”

Intimidation is the key word here. It applies not only to architecture and the products of starchitects, but to the assumptions, operations and fabrications of the larger art world as well. It reaches to a general public cowed by the subject of art. Lastly, it extends to critics who are themselves fearful of seeming insufficiently cerebral, or—most damning of all—anti-intellectual. All parties collude in what is, at base, a public relations hustle: the contrived superstition that the general public has no more business commenting on art than on string theory.

Keep in mind that lowbrows can be very smart people. It simply does not serve the art world clerisy to admit that misplaced intellection is anti-intellectual.

Silber’s acknowledgment of that displacement makes this slim book worth reading. In fewer than 100 pages of photos and text, it underscores the arrogance and philistine bent—a disguised anti-intellectualism—of much contemporary avant-garde ambition.

© 2010 Maureen Mullarkey