We are accustomed to thinking that verbal discourse (written or spoken) and visual communication are complementary. Word and image accompany each other, so we believe, in the same struggle to get to the truth of things. But maybe not. Could they be not only distinct but antagonistic ways of understanding? Or are images mere accessories to words, meaningless without verbal explanation?

What set me wondering was a flurry of unsmiling emails that came in response to the previous post. These were ones that said nothing at all about the written content but took exception—quite breathy in some instances—to the images. The first was deemed particularly grievous. Inappropriate! Ugly! Pornographic! Cancel my subscription! Or, as happens with email: Take me off your mailing list!

Since Roman Cieslewicz’ 1982 poster for the first production of Paris by Night unsettled some of you, I will not repeat it this time. Sturdier souls can easily scroll back for it. Or click here. Please do.

I chose that image because it is a pitch-perfect rendering of the phrase “culture of death” that has entered common use since John Paul used it in Evangelium Vitae. Cieslewicz’ illustration, conceived eleven years before the encyclical, condensed a broad concept of moral theology to a glimpse.

An evocative compression, it carries a caution that draws on the substance of a medieval Dance of Death. That skull against the woman’s loins warns against the legendary vanities and preoccupations—sex and hedonism at the top of the list—associated with modern café society and, on advisement from Toulouse Lautrec, Parisian night life. Those black stocking tops! Nothing more needs saying if you grasp them in mythic rather than dull realistic terms. Not to view the image as a caveat emptor is to miss it altogether.

Alberto Martini (d. 1954), an Italian painter/printer drew on the same myth for Danza Macabre Europea, his scathing series of five anti-German postcards circulating during World War I. Below, Wilhelm II appears as a peacock standing on a skull. Note the visual analogy between the kaiser’s boots and a doxie’s black stockings:

And while you look, take note of the reference to Islam on the lower right. Wilhelm II entertained a romance with Islam that was both personal and strategic. He shared with the Ottoman Empire a lust for world domination. Six years ago historian Sean McMeeckin, on faculty at Turkey’s Bilkent University, wrote The Berlin-Bagdad Express: the Ottoman Empire and Germany’s Bid for World Power. You can read Max Hastings’ review of it in The New York Review of Books, December 9, 2010. From the review:

There is concrete evidence,” writes McMeekin, “that Turco-German-jihad action plans were ready to go when the guns of August started firing.

But I do not mean to digress. Let me stay where I started: with images. The pairing of sex and death goes way back. It dismays me to see Catholics shield their eyes from contemporary variants of an ancient theme. It indicates a refusal to trust an intuitive means of expression that can leap frog over logical thought or reasoned explanation and yet arrive at the same point.

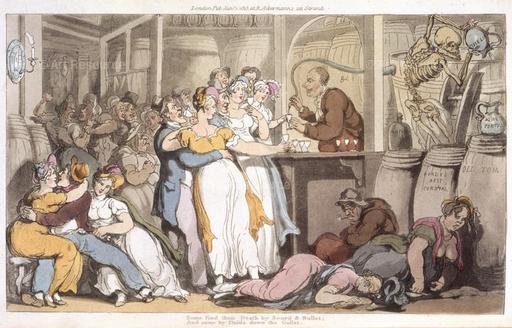

Here is Thomas Rowlandson’s raucous treatment of the bawdiness and other sins of the flesh (and there are others) that accompany nights out at the pub. This, before the Brits caught on to cabaret nights:

Death has had its empty eye socket on young women for a long time in Western iconography:

And, when it came to the sexes, played no favorites. Here, Death leads a comely young man in his last dance:

The seductive quality of Cieslewicz’ theatre poster is common to the theme. The culture of death would have no appeal, entice nobody, if it did not seduce. Deadly in the end, the serenade is captivating:

We have grown familiar with older depictions of the allegory. We are comfortable with the dancing skeletons, the sad strands of hair, and spilling entrails. These are the motifs popularized by the fifteenth century woodcuts of Michael Wolgemut, teacher of Albrecht Dürer:

But the Great Dance continues. It appears and reappears in unexpected ways. The costumes change, so do the pulse and cadences of accompaniment. But the movement from life to death follows a multitude of patterns. It is as much with us today as in Wolgemut’s time. His piper still plays.