“Doctor, Doctor, will I die?”

“Yes, my child, and so shall I.”

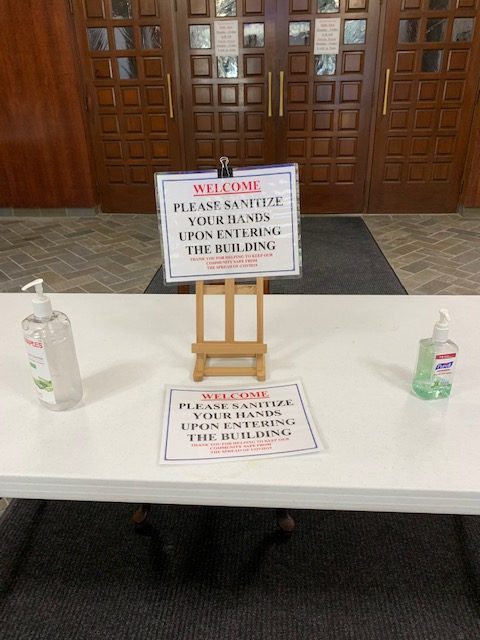

Hand sanitizer has entered the liturgy as both a stay against mortality and a sacramental displacing holy water. Coronavirus is not cholera but it might as well be. That is the unavoidable impression given by churches with dry fonts but multiple dispensers of sanitizer.

Every acute respiratory illness is serious. By no means is this latest Chinese virus to be taken lightly. But there is no point in my adding to the media drum beat. What matters here is the response to the virus by Church officialdom. There is something unseemly—not to say unmanly—in the common response of too many parishes to this particular strain of coronavirus.

What kind of men lend themselves so dutifully, submissively, and without complaint to a cruel media-manipulated panic that is lethal to a very small fraction of the population? It is not possible to respect a priest whose final word from the altar is “Stay safe.” I winced when I heard it.

Sin is okay, but a slight rise in temperature is verboten

My own local church, a handy gauge to others, requires a temperature check at the door. No one is allowed into the pews on Sunday until a church lady has come at them with a no-touch infrared thermometer. First you must scrub your hands with the sanitizer on a long table blocking entrance to the nave. Then you stand, as if before a firing squad, and wait for the remote sensor to be aimed at your forehead. (I asked the good lady if the digital display could give a reading of the degree of my lapse from sanctity. She looked offended.)

Holy water is gone but hand sanitizer flows by the gallon. In all candor, a bottle of Purell has set on a little shelf in our sanctuary for a good many years. Its presence dates back, roughly, to the CDC’s report The Global HIV/AIDS Pandemic, 2006. But at least there was some discretion to its placement stage left. This time, in the age of COVID, it has moved to center stage.

When church doors were unlocked in July, a bottle of hand sanitizer showed up right on the altar. To be sure, Purell is still on its side shelf. Sunday’s eucharistic ministers can still purge themselves of pathogens before distributing communion. Now, though, the priest keeps a medicinal-looking dispenser of his own on the Lord’s table top.

Hand sanitizer has been elevated to a sacred prop, an item of deference as commonplace as candles. The rubbing of hands together—out, out damned germ!—is the latest in demi-liturgical gestures. No one balks at this peculiar fetish. Quite the opposite. To satisfy popular craving for 70% ethyl alcohol, four—four—hand-sanitizing stations have been erected down the center aisle. Each one sports the same infantilizing symbol that illustrates how to clean our hands. Just in case we had forgotten.

As we walk up the aisle toward the altar, we glide from one floor sign to the next. Designed for people with the mental capacity of a toddler, the spaced rondels chirp: We are practicing social distancing. Yes, yes. The mind’s ear follows with a string of age-appropriate phrases: We are brushing our teeth. We are tying our shoes. We are picking up our toys.

In burlesque of purification

“I will wash my hands among the innocent, and will walk ’round Thy altar, O God.” Those lovely words of the ancient Lavabo have faded from the no-longer-new Mass. A perfunctory relic of the tradition, though still here, is half-erased. My parish Novus Ordo gets it out of the way quickly, offhandedly. The ritual is finished before there is time to remember the sweet tribute: “Lord, I love the beauty of Thy house, and the place where Thy glory dwells.” No time for the heart’s plea: “Destroy not my soul with the impious, O God, nor my life with men of blood.”

Not so today’s hygienic substitute. Come the moment to descend the altar steps and distribute communion, our priest pulls his mask up from under his chin, reaches for the redemptive sanitizer and makes a show of massaging it into his hands. He does a thorough job of it, as good as a demo on YouTube.

It is fair to wonder if liturgists of the 1960s had not projected their own hubris onto the rest of us by presuming that modernity was ill-suited to the humble supplication of the old Asperges. Implicit in its phrasing is recognition of one’s unworthiness and need of absolution. Standing at the foot of altar before High Mass in the old rite, the priest sprinkled the assembly with holy water while intoning an antiphon on behalf of us all:

Thou shalt sprinkle me with hyssop, O Lord, and I shall be cleansed; Thou shalt wash me, and I shall be made whiter than snow.

Which will it be: hyssop or ethyl alcohol?

Ritual hand washings are prevalent in Jewish law and custom. With our own venerable protocols held captive to something called relevance, a symbolic bond to our origins goes missing. Ritual cleansing is an act of prayer, an ablution that begs God to bestow on us the supreme gift: purity of soul. Carried into the early Church from Judaism, ceremonial purifications are an enduring link between modern Christians and the covenant into which Jesus was born. And within which he worshiped.

We hold close the words of St. Paul to the Romans: ” . . . remember it is not you who support the root, but the root that supports you.” If the root is neglected, allowed to wither, who are we? If we permit a craze for material cleansing to upstage the abiding significance of liturgical cleansing, what are we? What have we become?

Ask a priest who croons “Stay safe” and see what he says.