In an earlier post I registered dismay at the sight of the annual Christmas wreath hanging from the foot of the crucifix in my local parish church. A careful reader familiar with the lore of holly wrote to ask: Would I still object to the placement of the wreath if it were made of holly?

Yes, I would. And perhaps the reader would, too, if he had seen it. There is no way to know. Personal sensibility comes into play. Individual taste. To me, the history and symbolism of holly is one thing; the sight of a bewreathed crucifix is quite something else. It makes me wince—or laugh—to see them conjoined. Whatever else it might signify, holly asserts itself as an attribute of the Lord of Misrule:

Most friendship is feigning, most loving mere folly; Then heigh ho! the holly! This life’s most jolly.

However much a crucifix commemorates Christian trust in redemption, the cross remains a site of execution. I am not able to make the leap toward decorating an emblem of torture. The carol tradition is a bit . . . well, thorny on the matter.

In some northern European countries, the holly tree is called “Christ’s thorn” because the thorny leaves and blood-red berries are considered emblematic of Christ’s suffering. Many traditional English carols bind Christmas to the Cross:

Now the holly bears a berry, as blood is it red,

Then trust we our Saviour, who rose from the dead.

Consider a stanza of The Holly and the Ivy, sung to the melody of an old French carol. Gall is an immediately recognizable reference to the crucifixion:

The holly bears a bark

As bitter as any gall;

And Mary bore sweet Jesus Christ

For to redeem us all.

Still, emphasis remains most often on the festive uses of holly:

[We] bequeath this holly and this ivy wreath / To do him honour, who’s our King, / And Lord of all this revelling.

An older carol, its Latin roots showing, binds the holly to celebration:

Christ was born on Christmas day; / Wreath the holly, twine the bay. / Christus natus hodie.

Charles Alexander Johns (d. 1874) was both an Anglican minister and a devoted naturalist. His The Forest Trees of Britain (2 vols.), first published in 1847 and still available in print, endures as a classic text. Famous for the botanical accuracy and beauty of Johns’ drawings, it intertwines horticultural information with legends and traditions associated with Britain’s arborculture. The lyrical, the scientific, the folkloric and the devotional blend with an ease that makes the book a delight for modern readers while, at the same time, indispensable to naturalists.

Johns honors holly as an “incomparable tree” and the most important of the English evergreens:

Whether we wander in the woods when all is bare and stark save the trunks of trees, which are clothed with the borrowed verdure of the Ivy, and save the dark but cheerful array of armed leaves presented by the Holly; or whether, in the bright leafy days of summer, we detect it far off in the depth of the forest, reflecting light from its polished mail, as brilliantly as if every leaf were a mirror—at any season we should be sorry to miss it from our woodlands.

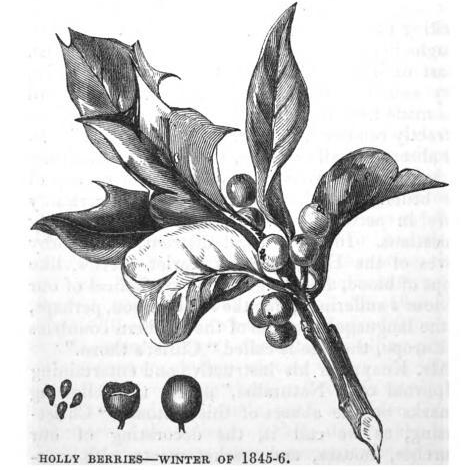

But welcome as the Holly is at all seasons, it belongs more particularly to winter, for then the bright, joyous appearance of it crimson berries, which from our earliest years have been associated in our minds with the festivities of Christmas, render the tree doubly conspicuous. What may be said of the Hawthorn is true also of the Holly; both these trees are emblematical of the season in which they are most beautiful, for it is quite as common to hear the Holly called “Christmas,” as the Hawthorn “May.” Indeed, its ordinary name appears to point to the use to which, from a very early period it was applied, namely, the decoration of sacred places at the Holy season of Christmas. For Dr. Turner [William Turner, M.D., an eminent 16th century naturalist], our earliest writer on plants, calls it “Holy” and “Holy-tree,” and the same mode of spelling is observed in a MS. ballad of yet older date in the British Museum.

Rev. Johns continues with mention of the Roman custom of sending boughs, together with gifts, to friends during the festival days of Saturnalia:

This method of shewing goodwill being at least harmless, it has been conjectured that the early Christians adopted it in order to conciliate their Pagan neighbors. In confirmation of this opinion, Bourne [Vincent Bourne (d. 1747), classical scholar and Neo-Latin poet] cites a subsequent edict of the Church of Bracara, forbidding Christians to decorate their houses at Christmas with green boughs at the same time with the Pagans; the Saturnalia commencing about a week before Christmas.

The Druids, too, decorated their quarters with evergreens in wintertime “that the silvan spirits might repair to them, and remain unnipped with frost and cold winds, until a milder season had renewed the foliage of their darling abodes.” But Johns’ most interesting conjecture of the origins of decorating with holly links the practice to the fall feast of Sukkot on the Jewish calendar:

May we not infer that the early Christians adopted the custom of decking their churches and dwellings with green boughs to shew the connexion between the Jewish Feast of Tabernacles, and the festival at which they commemorated the fact that “the Word was made flesh and dwelt”—or, as it may be more correctly rendered, “tabernacled among us?” . . . This conjecture appears to be quite as consistent with reason as any of the others which have been made, and certainly more in accordance with the piety of the early Christians.

“Tabernacled among us.” The loveliness of the phrase—the resonance of it—endears itself to me. And, I hope, to you. We who have been grafted on to the olive tree need to hold close what reminders we have of how deep our roots go.