Notices of Archbishop Paglia’s homoerotic mural began appearing in my e-box on Friday, with still more on Saturday. I regret not having paid closer attention before shrugging in dismissal. Diverted by art history and the aesthetics of the thing, I missed the crux of the story.

Truth to tell, the screaming headline put me off: Shocker: Francis-appointed Vatican archbishop featured in massive homoerotic painting he commissioned. Maybe it was the word shocker. So often does that precede something that ought be no surprise to anyone, let alone a shock, that I did not read past the opening paragraph on LifeSiteNews:

The archbishop now at the helm of the Pontifical Academy for Life paid a homosexual artist to paint a blasphemous homoerotic mural in his cathedral church in 2007. The mural includes an image of the archbishop himself.

A too-quick glance at the mural left me thinking that the most shocking thing here was the lumpen figuration and the then-bishop’s abysmal lack of aesthetic discrimination. So—I said to myself—patrons have traditionally appeared in works they commissioned. Paglia was simply following suit.

And the artist was homosexual? What matters—still talking to myself—is whether the art is good or bad, not the artist’s life. The presumed homosexual interests of Donatello, Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Benvenuto Cellini are well known. Yet the chatter has never been a strike against their work. Besides, Italian painting of sacred themes has long been a refined stop for connoisseurs of high quality male erotica. Not for nothing did E.M. Forster call Italy “the beautiful country where they say ‘yes’.” All those toothsome St. Sebastians come straight to mind:

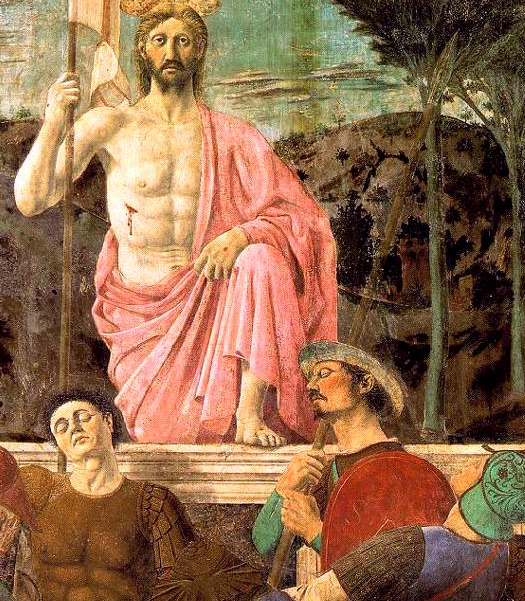

Western verisimilitude easily tips sacred subjects toward the profane. Say what you will about the era’s blameless preoccupation with the perfection of the human form, it is not anachronistic to see homoerotic elements in Renaissance and Baroque paintings commissioned by clients with distinct appreciation of male anatomy. Rubens’ Risen Christ affirms the Orthodox claim that sacred art waned in the West under the advance of realism. Since the eve of the Renaissance, goes the charge, the West has produced only secular art, albeit with a sacred subject:

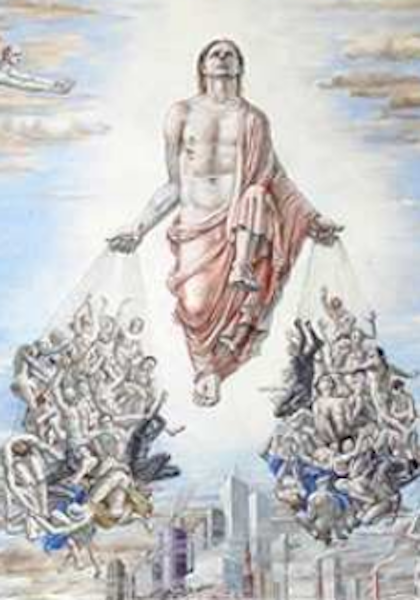

Too impatient to read Matthew Hoffman’s complete article, I saw only the pedestrian quality of Paglia’s mural—a leaden, unimaginative pastiche of its predecessors. It is a Fire Island resurrection scene that confuses several time-honored motifs and compositional conventions. Those many historic descents into limbo and falls of the damned render a clutch of naked sinners—some luminous, some drained by suffering—huddled together in dramatic coils, waiting out their purgatory or cascading into hell. Pre-modern pictorial narratives of salvation and damnation came from hands as lovely to contemporary secular eyes as to faithful ones. Even scenes of hell were endowed with a terrible, cautionary beauty.

But Paglia’s out-and-proud commission is decidedly ugly, as clumsy in execution as it is crude in conception. Most risible—sinful, in a painter’s view—is the mural’s witless appropriation of the central figure from Piero della Francesca’s sublime Resurrection of Christ. Aldous Huxley knew what he was seeing when he named this fresco “the greatest picture in the world”:

Compare the Piero with what the Argentinian artist, known back home for his male nudes, offered the bat-blind bishop:

The artist saw no reason to lower Christ’s left foot, neither to make the stance plausible nor eliminate comparison with the Piero. Instead, the foot hangs in the air, as if Christ were about to kick a soccer ball or stomp on one. What was the man thinking? Well, we know he was thinking about a local male hairdresser because, admittedly, he modeled Christ’s face on the fellow to keep the image from becoming “too masculine.”

Sunday morning, I took time to do what I should have done earlier. I read through the full article, looked more closely, and saw what I had missed in haste. This time, I was shocked. Though perhaps astounded is the better word.

Paglia’s narcissism—the urge to flaunt his liberation from the moral considerations he is pledged to honor—is stunning. It is a finger in the eye of congregants who trust in a priest’s fidelity to his vows. To place it in a public house of worship is treachery. It is also a declaration of Paglia’s own trust in his immunity from reprimand.

Let a priest, bound to celibacy, keep his sexuality to himself. Apart from all else, that is elementary manners. It is uncivilized to trumpet what any primitive tribesman understands: that there exists an inviolable boundary between what can be seen and what should be kept hidden. By forcing congregants to peep through a keyhole at his sexual inclinations—and suggested behavior—he mocks the moral sensitivities he is pledged to protect.

Abandoning reticence, Paglia disdains his own flock. He is taunting them. There is malice in that.

Ultimately, the core of the issue here is not about a mural at all. Not substantially. Nor is it even about Archbishop Paglia. It is about a degraded Vatican culture which props up a man like Paglia, awarding him authority when he should be handed sackcloth and ashes and packed off to a hermitage.

The true scandal here is the basis—which goes unmentioned—of Paglia’s confidence that he could broadcast his sexuality on a cathedral wall without fear of censure. On what protections did his certainty rely? Who are the enablers of this cocksure display of male bonding? From how high up the ecclesial ladder does Paglia’s insurance come? And why is the damned thing still there?

Paglia’s leanings have been on the wall for an entire decade. During that time, he has glided easily through the Vatican bureaucracy. Five years after the mural’s unveiling, Paglia was promoted to archbishop and appointed president of the Pontifical Council for the Family. It was on Paglia’s watch that the Council published a sex-ed program that, according to Hoffman:

. . . includes lascivious and pornographic images so disturbing that one psychologist suggested that the archbishop be evaluated by a review board in accordance with norms . . . which are meant to protect children from child abuse.

Last August, Pope Francis shifted him from the Pontifical Council to presidency of both the Pontifical Academy for Life and the Pontifical Pope John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and the Family. What business does this indiscreet, sex-happy man—put plainly, a creep—have to do with marriage and the family? What do his continued appointments, coming as they have in the wake of his billboard-sized disclosure, say about his boss?

Jack Kerouac called Tangier “a hive of queens.” Might we say the same thing about the Vatican’s internal patronage system? Paglia’s mural is best understood as a brash testament to a poisoned stream that runs through the Vatican nomenklatura.

Call it the Homintern. That word dates back to the 1930s and the belief that a clique of homosexuals had elite influence in the arts, theater—in all creative fields. It is a play on Comintern, short for the Communist International. It functioned in its day much like today’s term gay mafia but with one difference. It aligned homosexuals with Communists as wreckers of tradition and national boundaries, not only in the arts but in politics, institutions (including spydom), and manners as well.

This seems a good time to revive a term that comes to us from years W.H. Auden famously dubbed a “low, dishonest decade.” The ’30s spawned the ’60s, a ruinous decade which now sits at high table among key players behind the Vatican wall.