The oddities of Archbishop Paglia’s 2007 commissioned mural stirred interest in other works by Ricardo Cinalli, the Argentinian artist who painted it. Why him? Of the ten artists who auditioned for the project, what recommended Cinalli above the others? Presumably all applicants were adept at the human figure, all capable of managing the demands of a large-scale wall painting. What was the distinguishing feature of the winning artist’s portfolio?

Go ahead, take a guess:

The bulk of Cinalli’s output—prior to and close to the time of the commission—exhibits a will to startle, an inner necessity to stick a thumb in the eye of Mr. and Mrs. Bourgeoisie. Walter Benjamin’s wrecking ball is still swinging. Tact and subtlety crumble first. Some in the collector/commissioning class, no matter their age and station, still cannot get enough of whatever will incite bourgeois dismay.

• • • •

Trigger Warning: You will not like what you see here. But unless you look you will miss insight into Archbishop Paglia (and, by reasonable extension, the Vatican culture that sustains and promotes him). The eye is a fast lane to discernment. On show in Cinalli’s body of work is a drive toward trespass, an attraction fed by hostility toward norms. His is an art of the void, a figurative art that screams the absence of all sense of the meaning of man.

And that void is as legitimate a subject as any other. But the spirit that drives it does not invite consideration for the decoration of a space dedicated to worship of God.

So, friends, stay awhile for a brief tour through the portfolio of an artist who struck an axial chord in the ordained priest—now a high clerical bureaucrat—charged with piloting us through life issues and matters related to marriage and the family. [Paglia is president of both the Pontifical Academy for Life and the Pontifical Pope John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and the Family.]

• • • •

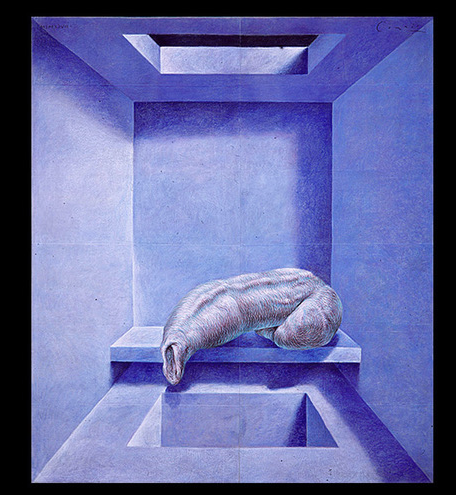

Cinalli’s affection for what Mikhail Bakhtin called “the lower bodily strata” is a defining feature of his work. Weighted toward the male nude, or parts thereof, his signature motifs are too obvious not to have featured in the deliberations of then-bishop Paglia and his co-curator, Fr. Fabio Leonardis. It is fair to assume the motifs were congenial to both men.

The point to keep in mind is that Cinalli’s sensibilities, apparent at the time of the commisson, were militantly transgressive. The grotesqueries and distortions of transgression function, as academics are fond of saying, as a “critique of the dominant ideology.” And the ideology in the dock nowadays is—more academese—heteronormativity. In other words, the idea that heterosexuality is a biological norm is an outworn credo. Time to scuttle it.

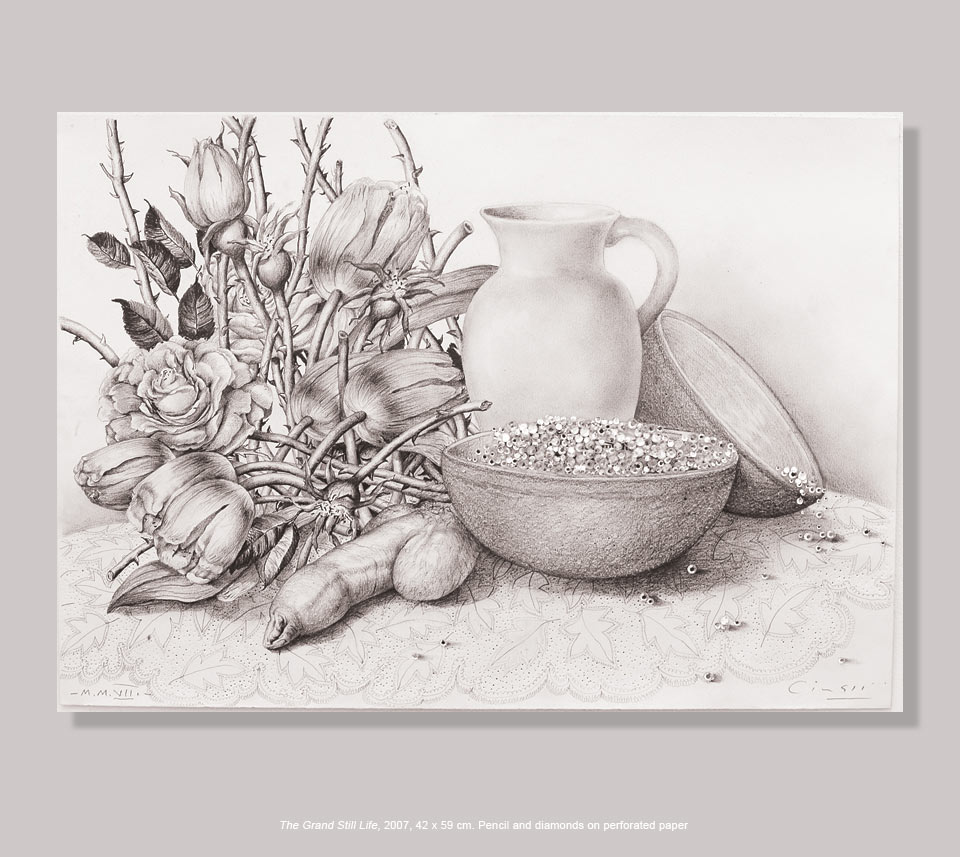

Look closely at Cinalli’s drawing (above). It is part of a stylish 2007 suite, Les Fleurs du Mal, modeled on Robert Mapplethorpe’s 1987 series of elegant, sometimes suggestive, flower photographs completed two years before he died of AIDS complications. Mapplethorpe, doyen of homoerotic pornography, was capable of visual puns. His wilting tulips suggested a double meaning while remaining real flowers. Cinalli, by contrast, is cheeseball blunt.

The ball keeps rolling. It is unclear to a woman why severed male genitals come under the heading of homoerotic. Eros is long gone from them. Cinalli’s penis-as-still-life looks wonderfully like something on offer in a butcher’s display case.

Nevertheless, that meat-seller analogy has some suitability viewed from a different angle. In his preface to Transgression, Michel Foucault welcomed “modern forms of sexuality” as “a solid and natural animality.” He applauded behaviors severed from generosity, fidelity, or humane significance. A bathhouse ethos, it killed Foucault of AIDS at fifty seven. (Fr. Fabio—he of the heart tattoo on the cathedral mural—also died in his fifties.) And as we know, certain animals are destined for the table. What Phillip Larkin termed “young meat” remains on a sufficient number of them to require the existence of a Vatican Commission for the Protection of Minors.

• • • •

Transgression comes to us as carnival; its animating spirit inhabits transvestism. During the liturgical year, Carnival flames out while Lady Lent prevails. That ritual progression holds today no less than in the days of Peter Breughel the Elder’s Battle Between Carnival and Lent. Cinalli, however, reverses Lent’s victory. His wigless transvestite [below] has been converted—convertido—away from piety and contrition to a liturgy of sexual fetishism. This gender bender has disposed of the redemptive universe signified by the crown of thorns and the Virgin tattooed down his arm. His right hand points to the left which joins thumb and forefingers as if in mockery of a priestly gesture:

In The Competition, the brute physicality of a cross-dressing male—the vanquishing figure in this arena—calls to mind the will to dominance that fuels the juggernaut called a gay rights movement (in reality, a demand for privilege):

• • • •

All figurative artists work in the shadow of art history, building on or borrowing from it where needed. Cinalli adopts classical models to illustrate a personal mythology of a male-only universe in which women, if they appear at all, are simply props.

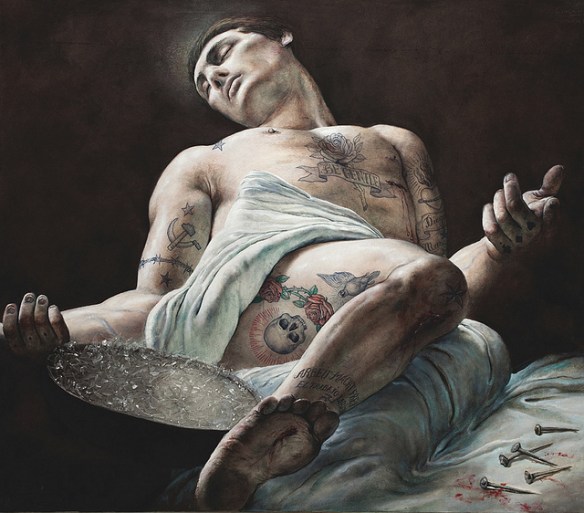

Shattered (below) is a fastidiously rendered inversion of traditional lamentation scenes. Andrea Mantegna’s haunting Dead Christ initiated the extreme foreshortening that was taken up as a challenge in perspective to subsequent artists. Mantegna’s Christ lies on the stone of unction, an image of sacrificial suffering. Borgianni’s later etching does the same. Both artists placed technique in service to the pity of the scene.

Pity disappears in Cinalli’s desacralized paraphrase. Gone is any opportunity for theological reflection. Only the sociological remains, implicit in those tattoos: the hammer and sickle, the death’s head. Is Cinalli’s figure really dead? That raised arm prompts the question: Is the figure merely in a stupor, sleeping off an induced transport of nihilistic self-immolation?

When it comes to formal and thematic sources to be mimicked, Cinalli is a magpie. Consistency lies mainly in the urge to enfeeble or outfox his antecedents. In 2007, Damian Hirst, a British artist-entrepreneur and showman, cast a human skull in platinum and covered it with diamonds. Titled “For the Love of God,” the thing sold for $100M to an investment group.

Two years later, Cinalli—who has lived and worked in London since 1973—imitated the stunt with a diamond encrusted rubber dildo. The downgrade in material from a real scull to a piece of rubber loses the frisson of Hirst’s gambit. The smart-alecky title, For the Love of Le God, is a bald statement of Cinalli’s enthusiasms.

Remember, we are strolling through these images to learn something about Paglia and his circle. Cinalli is a means to that end. If you like, you can view more of his portfolio here. What matters is the window onto an archbishop that the art opens wide. However oblique the view, what is seen is real.

What did the then-bishop have in mind by choosing an artist whose only relation—as artist—to the sacred is the cannibalizing or capsizing of the Church’s heritage of sacred themes?

In sum, if Cinalli’s body of work can be said to honor anything, it is maleness—not manhood, not the dignity of man, just a near-dehumanized maleness. Paglia awarded the brass ring to an artist sensitive to the sacred only for the purpose of negating it. Everything in Cinalli’s portfolio speaks against him as someone to be entrusted with a cathedral wall.

Neither aesthetic judgment nor pastoral prudence played a role in this commission. On the face of it, it resembles an exercise in gay nepotism. Or something close.