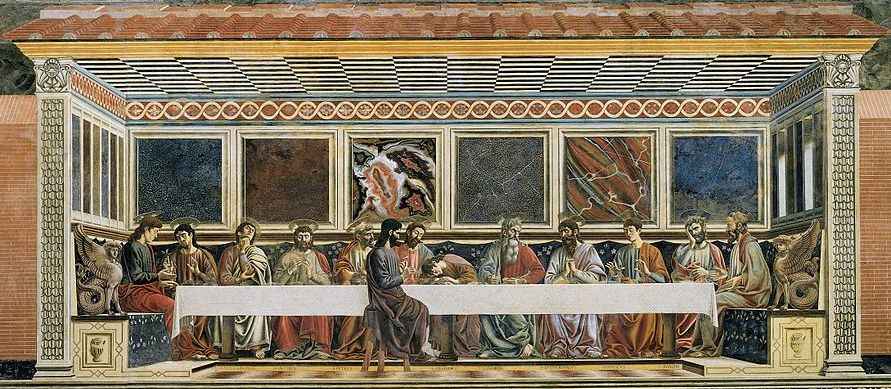

On Holy Thursday, Catholic imagination turns to thoughts of a painting. You know the one: Da Vinci’s Last Supper. Painted over a door in the refectory of a Milanese monastery in 1498, the mural is the sum of theological reflection on Jesus’ last Passover meal. Our own mental image of the event—who was there? what did it look like?—is fixed on Da Vinci’s interpretation. But an interpretation is all that it is. Yet we grant to pictorial orchestration the veracity of revelation.

I am thoroughly agnostic on the question of whether women were present at this seder. My attachment to a male priesthood, my deference to it, has nothing at all to do with the presence or absence of wives at what we call the Last Supper. Admittedly, my bond is cultural, largely aesthetic. (A woman in a Roman collar strikes me as a woman in drag, a signal of second-string manhood.) Even sociological. Theology I leave to others. Trained, systematic reasoning for an all-male priesthood is beyond my compass. Accordingly, I do not question it, have no argument with it, and carry no brief for the ordination of women.

What I do have difficulty with is the defensiveness, sometimes reaching manic levels, of the need to abolish wives—children, too—from that ancient Passover. Surely the ground for an all-male priesthood does not require purging Jewish custom from a Jewish ritual celebrated by Jews among themselves at that particular moment in history. Neither would admitting the possibility—or probability—of wifely presence necessarily support argument for female priests.

Because women were not named does not mean they were not there. In the rigidly patriarchal culture of the times, what matter their names? They were not free agents. Their very survival was contingent on connection to the patriarchal household. Divorce, permissible for paltry reasons, left them unhoused and without material support. Their children were the legal property of their husbands. (A nursing mother returned the child to his father’s household at a certain interval after a divorce.) Women were not admissible witnesses under Jewish law. As appendages to the households of the Twelve, wives’ names were irrelevant.

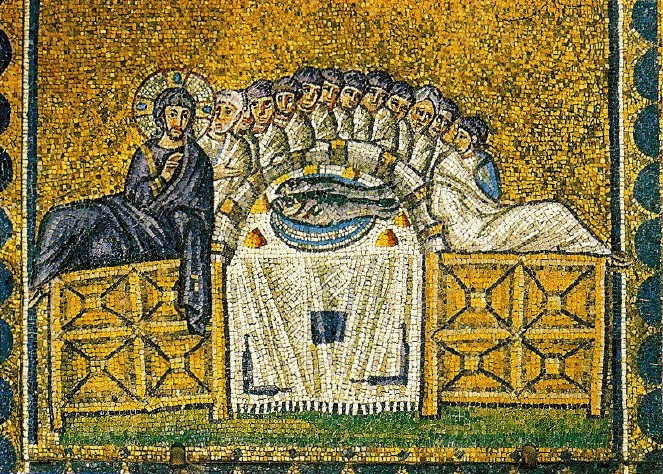

The primitive seder was not a female-free zone. Yet there is not a woman in sight in any known depiction of the last seder of Jesus’ life. Women have disappeared along with the lamb shank in the Ravenna mosaic. (How likely is it that Jesus would omit his mother from the familial meal on that of all nights?)

That vacancy reminds me—forgive a workaday analogy—of reunion dinners at the Harvard Business School. It was right and proper for wives to accompany their husbands. (Most grads at the time were men.) Deans and administrators addressed each gathering. Various CEOs, CFO’s, and successful entrepreneurs rose to give secular—treif—versions of do-this-in-memory-of-me. Toasts were raised. Politesse all around. Nevertheless, I knew quite well—as did every other wife—that the true and only addressees were the graduates themselves. Spousal attendance had no bearing on the nature or intention of the talks.

We hold dear St.Paul’s great dictum in Galatians:

There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free man, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus.

Paul does not discount creaturely inequality. Rather, he proclaims equality only in the matter of salvation. Whatever the accidents of birth, each one of us enjoys the same status before the Lord. But parity in moral status is not at all the same thing as equality in function. The supposed absence of women at the Last Supper has been taken as doctrinally central to a male priesthood. But is it? Is it not enough that Jesus of Nazareth was male? He did not walk the earth as an androgyne. His charisma and freedom of movement derived from his authority—physiological no less than cultural—as a man.

It is fitting that those who act ritually in his stead should also be men. The congruent beauty of that would hardly be diminished by a Last Supper that depicted Peter’s wife passing the maror.