SO WHO IS TUCKER NICHOLS? Whose kid is he?

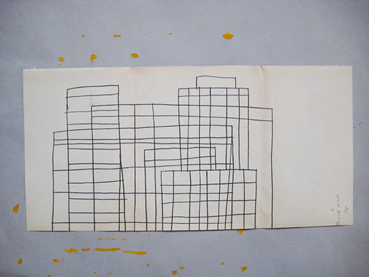

That was my first thought when I saw the name on an oversized, electric red envelope in the mailbox. At quick glance, it looked hand-addressed—immature block lettering dotted with a blot or two. It was the kind of Magic-Markering ten-year-olds send to each other by way of party invitations. Then I turned it over and saw a gallery’s return address. The envelope unfolded into a poster announcing Nichols’ third exhibition at Ziehersmith. (How ever could I have missed the first two?) The image was a hastily drawn grid, of sorts, that looked identical to this:

The one discernible difference, apart from paper color, is that Splash has blotches on the background. My invitation drops them onto the grid. The stunning ingenuity of this sent me to the artist’s CV to find out what institutions had nicked this exquisite chip off the cutting edge. It was—but surely you guessed—Yale. Well, Yale for an MA (1998) in East Asian Studies and Chinese painting, and Brown for a BA (1993) in art history, with concentration on China.

That explains it. Nichols’ markings are his up-to-date variation on freehand Chinese brush painting. Shui-mo with Magic Marker. Honestly, there is not much to say. A picture really is worth a thousand pensées in the art press. Herewith, a modern sample of the historic shui-mo, the sort of drawing Nichols studied—interrogated, is today’s word for it—in the library carrels at Yale:

And here is a sample from Nichols’ own hand, left to follow its bliss:

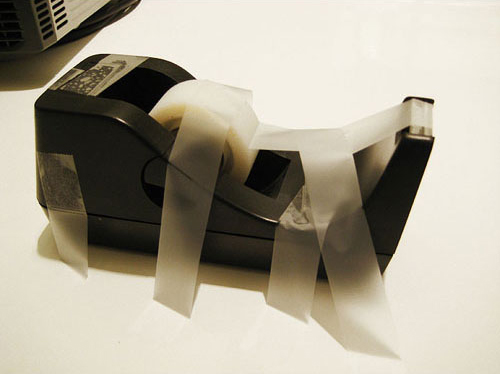

Nichols does more than just draw. He makes things, too:

This is what a culture fabricates when it disdains its manufacturing base and loses the traditions that go with manufacture—bodies of expertise, pride in craft—and the will to sustain them. All it can do is cannibalize itself and call the spectacle of devouring art.

What, you ask, does manufacturing have to do with contemporary art? Much more than we permit ourselves to think. A people has to make something. So, willy nilly, postindustrial culture trains its children to make an industry out of marketing aimless ephemera—postindustrial folk art gilded with expensive credentials from once-elite institutions. Academically sanctioned cottage industry fills the vacuum left when armories and factories disappear. In short, we adapt to the loss of authentic productivity by making landfill. It comes disinfected by the rhetoric of art appreciation, but is landfill nonetheless. And the waste is endorsed by equally credentialed promoters and middle men who do not recognize themselves as parasites on an exhausted civilization.

There is something prophetic in the difference between Nichols’ slack, self-indulgent hand and the disciplined Chinese one.

© 2010 Maureen Mullarkey