THE REOPENING OF PAUL THIEBAUD’S uptown gallery is a welcome event. Established on the West Coast, the gallery launched a New York branch in 2005. Four years later, the gallery closed the shutters and hung up a “by appointment only” shingle. Hearts dropped among those who loved the quality of its exhibitions and the pleasure of viewing them in the intimacy of a brownstone setting. Happily, it has opened its doors again with a splendid show of recent paintings by Wayne Thiebaud, father of Paul.

At a certain point in the career of an artist as gifted and esteemed as Thiebaud, there seems little left to say. All that matters has been stated. His reputation has been made; his place in American art history securely carved. A critic’s urge to stay mum and silently genuflect is very strong, if only to avoid repeating the rightful encomiums of Thiebaud’s life time. Still, there are subtle surprises among these recent paintings, all completed in 2009-10.

The accompanying catalogue includes David Anfam’s essay titled “Plato at the Dairy Queen.” Just so. In all Thiebaud’s painting, unspoken truths are at play under the surface of unexceptional objects. Creative generosity toward the commonplace takes us on an engaging romp through the whatnots of ordinary life: two and a half cakes, a slice of peanut buttered bread, a case of candy trays. Yet something more, not quite definable, prompts Anfam to say: “The knack is to grasp that Thiebaud’s cheap, familiar and transient motifs are wedded indissolubly to a larger whole.” (I would not call them cheap. Simply overlooked.) In the still lifes, that larger something hints at an ultimate goodness at the heart of things.

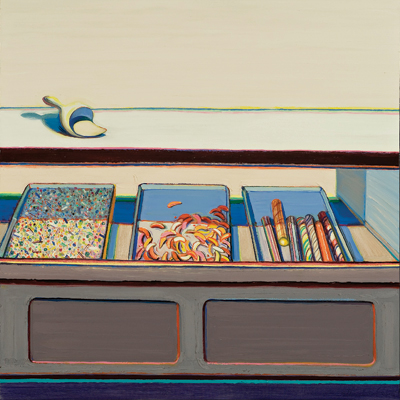

Thiebaud’s homily on the Good begins with a luminous Panama hat, its crown shaded by piping hot glazes. Who knew what glory there could be in shadow. Nearby, the disarming image of a child’s shoe bears the charm of an unspoken drama. Shoes are not the only things intended to go two by two. “Candy Trays” (2010) is classic Thiebaud. An austere, lateral composition with each detail exquisitely poised, the candy display rises to the dignity—touched with frolic—of those longitudinal arrangements that mark 17th century Spanish still life.

“Winter Ridge” (2010) takes a familiar motif—the vertiginous diagonal of a hillside—only to set great shards of ice tumbling down it. Gone is the whimsy of earlier ridge paintings with their line of cows, trees or beachgoers in giddy descent. These sharp, angled ice fragments suggest splintering glass. On second glance, the image induces a certain chill, as if Hans Christian Anderson’s distorting mirror had shattered over the Golden State. A similar sense of conflicted significance emerges from ”Mountain Roads” (2010). A winding road circles upward around an impossible piece of California terrain that mimics the tiered contours of Bruegel’s “Tower of Babel,” a 16th century response to the overbuilding and overconfidence of Antwerp, the boom town of its day.

“Intersecting Streets” (2010) depicts the same extreme plunge of earlier cityscapes. This time, though, the once-daring, even brash, sovereignty of San Fran has taken on a hint of sugarplum sweetness in coloration. Elsewhere, the Napa hills—soft as blancmange—look ready to slip into a Lollipop Sea.

Thiebaud is as always. Only California has changed.

© 2010 Maureen Mullarkey

Update: The reopening was brief. Paul Thiebaud died in California on June 19th. His obituary is posted here on the website of his San Francisco gallery. In the words of an old prayer: May God grant him refreshment, light and peace, forever.