They get into your blood after awhile, all our sugared Christmas images—candied madonnas, honeyed bambini, angels that look like Vienna choir boys. One more cottage-in-the-Shire, with glitter on the snow-covered roof and a lantern in the window, and I will need an insulin injection.

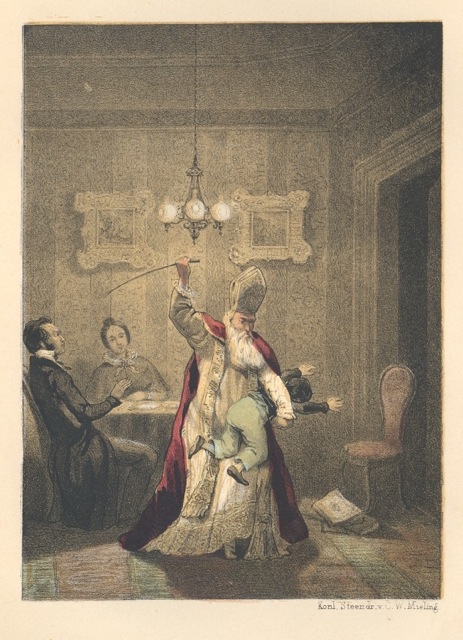

This 19th C. lithograph below came just in time. It dates from the days, long-forgotten now, that smart-mouthed cubs—little incorrigibles—could find a lump of coal in their stockings. That was before self-esteem was sacralized and any offense against it risked being reported to social services and deemed actionable. I emailed it around to friends, not expecting anyone to raise the specter of child protection laws.

But one friend writes wondering why the image should appeal to me. I detect a note of nervousness. Does my relish in it reveal a hidden strain of severity—cruelty, even?—that she had not previously noticed? She is not amused.

Oh, dear! My friend has never been around children much. Perhaps that explains it. Even so, I had not thought that the humor of it would need any explanation. Certainly not by anyone who keeps up on the news. In the wake of recent tantrums by spoiled college students at elite schools across the nation, St. Nicholas tanning a backside—a deserving one, I trust—warms the heart.

Today’s fledgling brown shirts, rehearsing for tyranny tomorrow, might have benefited in their tender years from chastisement by a judgmental St. Nick. Before their self-absorption had hardened into the despotic urges of social justice warriors, a spell of disapproval—which the saint’s raised cane represents—might have come as a saving grace.

But enough of the present. Stay with the past awhile longer. Old Christmas cards are captivating. Within the charm of the artwork breathes an intuition of Christmas as a shared symbol of the power of relationships, especially family ties. It is the ethos of family that is celebrated—a subtle but significant difference from displaying one’s own family in the manner of our contemporary Christmas snapshot card. Washington Irving, in The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, stated it this way:

. . . our thoughts are more concentrated, our friendly sympathies more aroused. We feel more sensibly the charm of each other’s society, and are brought more closely together by dependence on each other for enjoyment. Heart calleth unto heart, and we draw our pleasures from the deep wells of living kindness which lie in the quiet recesses of our bosoms.

Religious images are few. The Holy Family rarely, if ever, appears in them. Instead, they are infused with sense of the holiness—the venerable wholeness—of family itself.

Modernity’s Christmas card industry began at the initiative of Sir Henry Cole (1808-1884). Born in Bath, Cole was both a civil servant, an enterprising inventor, as well as founder and first director of the Victoria & Albert Museum. In 1843 he commissioned John Calcott Horsely to design a card that would be printed and sold specifically for Christmas. The card was produced for the British market in two versions: a colored one for sixpence, and an uncolored one for five. Both illustrate a family celebrating together at table. Herewith, for sixpence:

No, Virginia, the American greeting card industry did not begin with Hallmark. It was Louis Prang (1824-1909), a master printer and publisher, who brought the commercial Christmas card to the United States. Born in Breslau, Silesia, he immigrated as a political refugee in 1850, settled in Boston, and went on to develop chromo-lithography, the basis of the modern printing industry.

In 1874, Prang printed a selection of Christmas cards for export to England. The print run was a great success; the following year he produced for the home market as well. Popular enthusiasm for his cards earned him the title “Father of the American Christmas Card.” (Women noted in their diaries how many “Prangs” they had received on a given year.)

L. Prang & Co’s publishing ventures were broader and more sophisticated by today’s standards than his Christmas cards. But the cards served a particular locus of sensitivity. Before the status of sentimentality went into decline, Prang provided an American audience with mass market evocations of gentle sentiment. Necessary to heart and hearth, these were in vogue as tender spurs to a social conscience as well.

This was an audience that read Dickens and was familiar with the sentimental traditions that shaped him. It adhered to a trust in moral sentiment, closely aligned with, but not identical to, the affections. Emotion, after all, is bound to the substance of life. And, so, to art as well— including the art of mass produced greetings.

Art historian Nicola Brown, in a study of Victorian painting and the “problem” of sentimentality, puts things well:

To look properly, I argue, is also to feel.

And simply to circle back around to where this tour started, one of the emotions it is proper to feel is displeasure.