Every thoughtful Christian is invited to learn what is possible about Jesus in the context of first century Galilee and Judea. The much publicized Jesus Seminar, with its biases, stagecraft and colored-bead consensus, has skewed popular understanding of what we can grasp of the reality of Jesus of Nazareth in his own time and place. Nevertheless, respect for the tools of modern historical research keep us close to the words of Benedict XVI, spoken in November, 2012: “. . . faith is a continuous stimulus to seek, never to cease or acquiesce in the inexhaustible search for truth and reality.”

John P. Meier introduces his own study of the Jesus of history with this summons:

In view of Jesus’ impact on all of Western civilization no person of any religious persuasion can be considered truly educated today if he or she has not investigated to some degree what historical scholarship can tell us . . . The unexamined religious life—or even irreligious life—is not worth living.

Fr. Meier, writing from within a Catholic context, admits there is “no neutral Switzerland of the mind” in the world of biblical scholarship:

The rejection of a traditional faith stance does not mean neutrality; it simply means a different philosophical view that is itself a ‘faith stance” in the wide sense of the phrase. . . Whether we call it a bias, a Tendenz, a worldview, or a faith stance, everyone who writes on the historical Jesus writes from some ideological vantage point; no critic is exempt.

Meier distinguishes between the historical Jesus and the Jesus of faith. Yet they remain tethered, necessarily so if theology is not to slide into poetry. Or provide pious-sounding cover for secular agendas. When “doing theology” dwindles into a species of creative writing, Jesus evaporates into an abstraction. He becomes useful, the patron saint of whatever political or social credo prevails at the moment.

A prime example of Jesus-put-to-use is the anachronistic one who inhabits Laudato Sí. Environmentally sensitive, this Jesus does not command the winds. Like an exemplary modern, he is simply in tune with them.

Too little attention has been paid to the language of Laudato Sí. The text betrays a touching case of status anxiety.

Who was it—John Lukács?—who characterized our age as one in which moving left was the way to move up? Rather like becoming Episcopalian if you were raised Southern Baptist in the old days of WASP ascendency. It is too late to go Episcopalian. The swank thing now is to veer left by going green.

Intellectual social climbing is obvious in that section of Laudato Sí headlined “The Gaze of Jesus.” To anyone familiar with academic jargon, particularly feminist lingo, the word gaze sends up a flare. Every clued-in mortal on the planet recognizes it. Hearing it, secular elites know that they are in the company of a fellow traveler whose foot is on the straight way. Which, of course, veers in only only direction.

The gaze is a polemical term. Grievance lurks in it. Why no thought has been spent on it puzzles me. The word signals that the men who fashioned and delivered Laudato Sí yearn to be counted among the cognoscenti. That means having credibility with Those Who Know Better, all of them resident on the left. Regard for truth is not the motivating force behind the Vatican’s adoption of the Lacanian gaze. Rather, it is spurred by an urge to be recognized as European intellectuals. Vatican thinkers want to be seen having moved up in the grey cell department.

A Quick Review

Attention to the gaze, popularized by Jacques Lacan, takes its prevailing color from Michel Foucault who raised the innocent word glance to a power relationship. By a tyrannical act of surveillance, the one who gazes dominates the gazee. Every object of the gaze is oppressed by an imbalance of power between the two. Feminists take umbrage at the male gaze; acolytes of Edward Said reject the colonial and postcolonial gaze. Add the consumer gaze, the tourist gaze, and whichever others you can invent. There are gazes galore, each of them exploitative. They are degrading even to the gazer, a captive of perception.

Consider the day-tripper/tourist gaze:

Limned by an Englishman, this is a fine example of the colonial gaze:

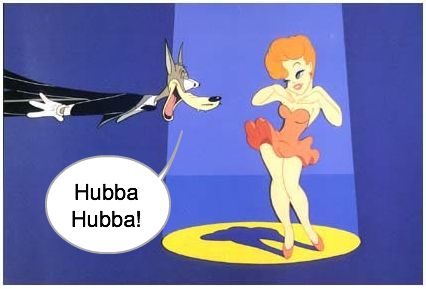

Gazes can intersect. Herewith, the male gaze and the colonial gaze combined:

Below, a variety of the consumerist gaze:

Authors of Laudato Si, self-conscious fellows, swing the pendulum the other way by positing “The Gaze of Jesus.” The hated male gaze, of which only heterosexual men are deemed guilty, has been destroyed by the egalitarian gaze of Jesus of Nazareth. Laudato Sí bends scripture to suggest Jesus’ modern sense of ecology, his sympathetic equality with nature: “He was in constant touch with nature.”

Jesus used pastoral imagery—the fig tree, the mustard seed, the lily field— because they were the stuff of common experience in the agricultural society in which he lived. But it is inappropriate to equate ancient Judean rhetorical tropes with the sensibility suggested by the modern phrase in touch with. That phrase and its animating concept have a Hallmark ring unsuitable to a solemn document. It prescinds from the circumstances of Jesus’ own era and situation, an anachronistic misplacement that serves politics, not faith.