What Child is this who, laid to rest,

On Mary’s lap is sleeping?

Whom angels greet with anthems sweet,

While shepherds watch are keeping?

(William C. Dix, 1865)

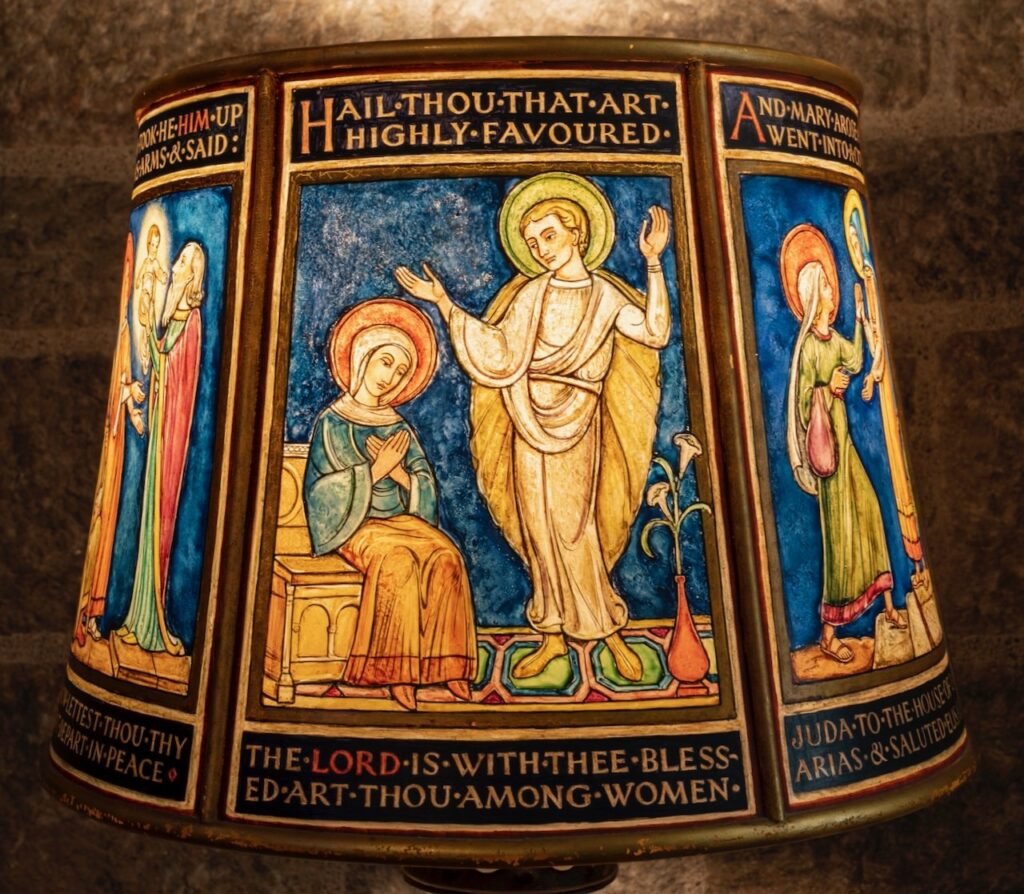

This Advent, following the October 7th massacre of Israelis, calls us to remember that the Child we wait for is a Jewish child. He was born of a Jewish mother, flower of the seed of Abraham. We know by heart that passage from John: “The Word became flesh and dwelt among us.” Yet we say the words without pausing to marvel that the Word took Jewish flesh. Not Greek or Roman, not Persian, Egyptian, nor that of any other peoples. And the blood that soaked a timber on Golgotha was Jewish blood.

In recollection, the mystery of the Incarnation deepens.

• • • • •

St. Paul drew from the Book of Genesis to remind non-Jewish converts in Galatia of the redemptive mystery passed from Abraham to the followers of Jesus: If you belong to Christ, then you are Abraham’s seed, and heirs according to the promise. (Galatians 3:29)

Note that these early Christians are named as heirs, not usurpers. They do not displace the progeny of Jacob. Rather, through faith in the death and resurrection of one Jew, the Rabbi of Nazareth, they become co-inheritors of the covenant between God and His people.

• • • • •

Mother Emmanuel was the religious name of Joan McIver, OSU. She was my theology professor in junior and senior years in an Ursuline college. She could not have chosen a name more revelatory of the character and depth of her Catholic sensibility. A biblical scholar in her own right, Mother had studied at New York’s Yeshiva University. She brought to her classroom deep knowledge of Jewish history together with reverence for Jewish philosophy, and ethics.

All students in the last semester of senior year were required to take her course “Contemporary Moral Problems.” It engaged ethical and doctrinal issues as they emerged in settings both ecclesial (e.g. pastoral and disciplinary knots) and secular (e.g. just war theory; topics under the umbrella of social justice). On the last day of class, she delivered a closing statement:

All the concerns we’ve examined this year will be worked out in God’s good time. But remember: for you as Christians, the single most critical religious issue is this—What is your relation to Judaism?

At twenty, her question electrified me. This Adventtide it resonates more than ever.

• • • • •

Even now, in the wake of October 7, Catholic media remains gripped by palace intrigue in Rome. The fixation is a red herring that takes our eyes off the end game. The machinations and ambitions of Vatican honchos, pretenders and company men—and their abuse of holy men like Cardinal Burke and Bishop Strickland—are galling. But not of ultimate consequence. The Church has always had its all-too-human schemers. Of far greater import for the future of the Church is the Israel-Hamas war. In the fate of Israel lies the fate of the Church.

Christianity has been rendered close to extinction in the Middle East, its birthplace. A resurgent Islam is on the move, abetted by Islamo-fascists and anti-Western progressives in government, in academia, and among bien pensant globalists in the Vatican. We have no guarantee that the star and crescent will never fly over St. Peter’s. The basilica’s status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site—in sum, a museum—offers no insurance against Islamic advance. In 2020, Turkey dismissed UNESCO’s secular embrace of Hagia Sophia. Once the consummate symbol of Eastern Orthodox Christianity, it is now officially the Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque.

Shelley’s “Ozymandias” comes to mind. Though the stones of the Byzantine cathedral still stand, the Christian culture that laid them is a “colossal wreck” on ground that stretches far away.

The Quran identifies St. Peter as one of Jesus’ steadfast helpers in doing the work of Allah. If a sickly, compromised West sacrifices Israel to short-term geopolitical interests, it is only a matter of time before the Vatican basilica will become known as Shamoun as-Safa Grand Mosque. (In Arabic, Peter is called both Shamoun as-Safa and Shamoun ibn Hammoun.) It might take centuries or it might come in decades. But it will happen.

• • • • •

O come, O come, Emmanuel,

And ransom captive Israel;

That mourns in lonely exile here,

Until the Son of God appear.

Rejoice! Rejoice! Emmanuel

Shall come to thee, O Israel.

This beloved hymn dates back, in various renditions, some 1,200 years. It adds a Christological gloss to a passage from Isaiah: And the ransomed of the LORD shall return and come to Zion with singing; everlasting joy shall be upon their heads; they shall obtain gladness and joy, and sorrow and sighing shall flee away. (35:10)

We rarely sing, or hear sung, the last stanza. Its references—to Israel’s twelve tribes and the giving of the law to Moses on Sinai—are utterly Jewish. Its Pauline character announces itself in that phrase “shall come.” For Christians, the LORD has already come, and will return. Jews still wait for Him to show up:

O come, O come, thou Lord of Might

Who to Thy tribes, on Sinai’s height,

In ancient times didst give the law,

In cloud, and majesty, and awe.

Rejoice! Rejoice! Emmanuel

Shall come to thee, O Israel.

For Jews and Christians alike, the burden of waiting weighs the same. Equally heavy are the demands of a soul-scalding trust in that exultant expectation even in the face of evil.

• • • • •

Pinchas Lapide, an Orthodox Jew and luminous New Testament scholar, cited this prayer scrawled by an nameless Jew on a wall of the Warsaw ghetto as it was under siege:

I believe, I believe, I believe with a perfect faith in the coming of the Messiah; in the coming of the Messiah I believe. And even though he tarry I nevertheless believe. Even though he tarry, yet I believe in him. I believe. I believe. I believe.

How much of the Christian West retains the same Job-like certainty this Adventtide?