Two days after his election, Leo XIV summarized the keynotes of his reign. In his first formal address to the College of Cardinals, he pledged compliance to the works and aims of Vatican II: “I would like us to renew together today our complete commitment to the path that the universal Church has now followed for decades in the wake of the Second Vatican Council.”

He emphasized adherence to the fundamental priorities “masterfully and concretely” set forth in Evangelii Gaudium, Pope Francis’s first apostolic exhortation delivered in 2013. Leo’s précis of those basics begins on a firm note: “return to the primacy of Christ in proclamation.” It dwindles from there into familiar tropes e.g., growth in synodality, and care for that easily politicized abstraction: “the least and the rejected.” His promise to engage in “courageous and trusting dialogue with the contemporary world in its various components and realities” was a high-sounding generality too vague to submit to definition or examination.

Absent from Leo’s cursory summary was any reference to the most salient—and worrisome—links between himself and Evangelii Gaudium. The first was his devotion to Pope Francis’ formal repudiation of the historic legitimacy of capital punishment. Absolute rejection of the death penalty is sewn into the fabric of Leo’s fidelity to Francis’s sentimental humanitarian mindset, token of a more encompassing ethos.

Burrowed deep into Francis’s fifty-one-thousand word exhortation are multiple declarations of that ethos. Passages in Chapter Two (“The Social Dimension of Evangelism”) and Chapter Four (“Amid the Crisis of Communal Commitment”) read like excerpts from a seminar paper in liberation theology. These reduce evil to structural causes—thereby detaching it from an individual’s actions. Individual responsibility and the concept of sin fray under the weight of politicized consensus. [More on this in a later post.]

Let us begin with capital punishment.

Concern here is not whether the death penalty is warranted in the child rape case cited below. That argument belongs elsewhere. What matters was Prevost’s assent to Francis’s sweeping opinion that “a new understanding has emerged . . . . Consequently, the Church teaches, in the light of the Gospel that the death penalty is inadmissible because it is an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person.”

In 2018, Francis re-phrased the Catechism, coming within a hair’s breadth of declaring the death penalty an intrinsic evil. He overwrote two millennia of the Church traditional teaching that legitimate public authority had the right and the duty to impose the death penalty in cases where such sentence was proportionate to the crime. In that year, enlightened thinking goes, the conscience of Church was roused from its long, dogmatic slumber.

Dignitas Infinita, published by the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith [DDF], finished the job. It administered the coup de grâce to the death penalty in 2024. Then a member of DDF, Bishop Prevost signed on to its revelation that “the death penalty… violates the inalienable dignity of every person, regardless of the circumstances.” (emphasis mine).

In short, Leo XIV endorses Francis’s dogmatic innovation. Imposition of the death penalty is no longer a matter requiring prudential judgement. Capital punishment is now deemed an elemental evil alongside abortion and euthanasia.

Neither fair trial under legitimate authority nor monstrous cruelty can justify capital punishment. Progressive minds now deem the death penalty “inadmissible because it is an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person.” Consequently, as Francis’s 2018 revision intoned, the Church “works with determination for its abolition worldwide.”

Leo XIV endorses Francis’s obligatory fraternity with the worst among us on the grounds of our shared human dignity.

Down to cases: a child rape in then-Bishop Prevost’s diocese

In April, 2022, a forty-eight-year old taxi driver abducted and raped a three year old girl in Chiclayo. [Two Peruvian papers of record stated “under three.”] After a fifteen-hour search, the child was found lying amid cardboard boxes, hands and feet tied with packing tape, unconscious, and in need of hospitalization. Peru’s health insurance program, EsSalud, reported that she had undergone “reconstructive surgery.” That said all that was needed about internal injuries wreaked by an adult male on the body of a child just past toddlerhood.

The horrific rape electrified the entire country. People took to the streets in Chiclayo, in Lima, and throughout Peru calling for “The Monster of Chiclayo” to be punished in the extreme. Many carried white balloons, a poignant symbol of innocence, purity, and solidarity with little Damaris and her family. Demonstrations were accompanied by heated calls for the death penalty—which had been outlawed in Peru in 1979.

In response to widespread outrage, Chiclayo’s mayor canceled celebrations for the city’s 187th anniversary. The regional governor, Luis Díaz, recommended the death penalty in cases involving crimes against children. He also proposed that Peru withdraw from the Inter-American Court of Human Rights which forbade capital punishment within its jurisdiction.

Robert Prevost, then-Bishop of Chiclayo, tacked the other way. He regretted the abuse, calling it lamentable, an adjective as mild in Spanish as in English. He sympathized with the family, telling them there is no way to soften the pain felt at the abuse. Nonetheless, “blood for blood is no answer.”

La Republica quoted Prevost:

“This case in unfortunate. The causes and reasons have to be examined [Se tiene que ver las causas y razónes. . . ) in order to reform society, which implies the education of children and young people so that this kind of case does not happen again.”

In this vein, he asked the justice system to act efficiently and speedily, although he stressed that he is in favor of life at all times. “In the Church we teach that the death penalty is not admissible, not even in a tragic event like this. We have to see other ways of seeing justice.”

Prevost asserted that vengeance is unworthy of a human being, and instead diminishes his personhood (su condición de persona).

In sum, Bishop Prevost followed Bergoglio in dismissing the Church’s traditional magisterial distinction between revenge (illicit) and expiation (licit). Thus, two millennia of Catholic moral teaching was moth-balled, a preliminary to eventual erasure.

Is chemical castration an acceptable option in cases of sexual assault?

Not to Prevost. He voiced skepticism about chemical castration: “Trying to control these manifestations (of crime) must be addressed in depth. This measure, as a deterrent, is not effective. Experts will have to evaluate.”

Prevost is not an expert. Hence, his peremptory dismissal was untenable. It was also incompatible with a nuanced discussion by physicians published by NIH’s National Library of Medicine. For obvious reasons, surgical castration produces “definitive results, even in pedophilic offenders.” However, chemical castration “also results in very low levels of recidivism despite the strong psychological factors that contribute to sexual offending” so long as medication continues. To insure against relapse, “comprehensive psychotherapeutic treatment” is required in tandem with anti-libido pharmaceuticals.

So then, is chemical castration treatment or punishment? What is the role of informed consent? Answers are outside the compass of episcopal opinion. What earns attention here is Prevost’s insinuation that the crime of rape is a symptom [“manifestaciones“] of something else. Impersonal social conditions, not human evil, lurk in the background of his language: “The Diocese of Chiclayo rejects sexual abuse, violence, kidnapping, and human trafficking. I believe it is important to seek the root causes of such acts and find solutions.” [emphasis mine]

To paraphrase Dr. Johnson, root causes are the last refuge of the scoundrel. Or the sentimental humanitarian. Bishop Fulton Sheen knew better: “A man who has been told that everything is a symptom never need accuse or judge himself or ask to be judged.” (Psychoanalysis and Confession, 1948)

Prevost’s language shunned all reference to the traditional principle of expiation. He conflated the retributive purpose of punishment—upheld by Aquinas—with vengeance. Under the new dispensation, the dignity of the rapist is undiminished by depravity or deliberate cruelty. It remains sacrosanct.

The dignity of the shattered victim goes unmentioned.

• • • • •

That word “dignity” has become the modern episcopal solvent of all moral distinction between forgiveness and exoneration. On what does man’s dignity rest? What does “made in the image of God” mean if it it does not refer to man’s conscience? To the reality that we are moral beings, the only species able to conceptualize good and evil? The single creature capable of distinguishing between right and wrong and caring about the difference? When a man violates the demands of God-given conscience, has he not compromised or debased his God-granted dignity? What else is conscience for? The Church understood that question for two millennia. But progressive minds presume to know better now.

When a lion sinks his teeth into a lamb, no moral principle applies. The lion is as innocent as the dead lamb. But when one human being willfully savages another for his own corrupted pleasure, moral judgment kicks in. The individual’s act cries out for restitution. And, yes, for anger.

• • • • •

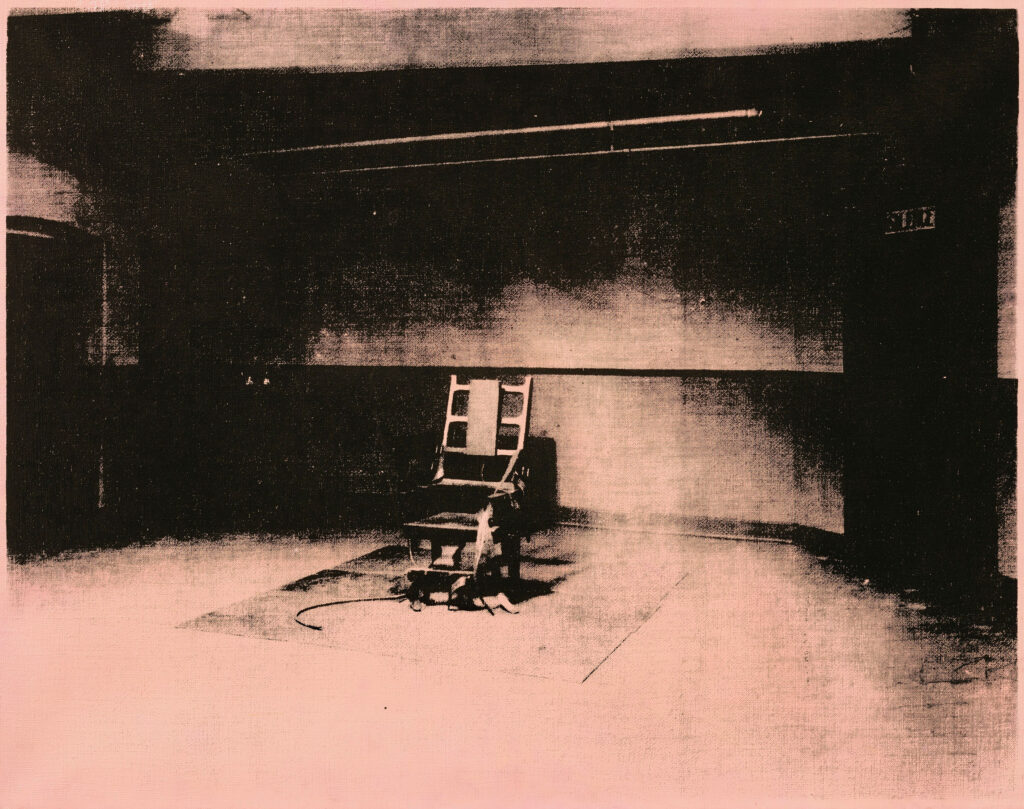

By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed, is a sound, compelling defense of capital punishment from the perspective of traditional Catholic teaching. Co-authored by Edward Feser and Joseph Bessette, it puts paid to platitudes and the tyranny of emotion over argument. From the text:

The desire for just punishment reflects not our worst instincts but some of our best. It orients human behavior to the natural moral law and in so doing provides the foundation for retributive punishment, which . . . is essential for promoting the common good. . . . Men should be angry at injustice and should desire, as the bishops say, to “restore the order of justice.”

In his extended treatment of the passion of anger, Aquinas is quite clear on this. He approvingly quotes John Chrysostom: “Without anger, teaching will be useless, judgments unstable, crimes unchecked”; and “He who is not angry, whereas he has cause to be, sins. For unreasonable patience is the hotbed of many vices . . . . “

Feser and Bessette remind us of the teaching of Pope Pius XII whose teaching on crime and punishment relied on systematic arguments and rational analysis rooted in scripture, not merely diktats from the papal office. Addressing an international convocation of histopathologists meeting in Rome in 1952, Pius stated:

Even when it is a question of the execution of the man condemned to death, the State does not dispose of the individual’s right to live. It is reserved rather to the public authority to deprive the criminal of the benefit of life when, already, by his crime, he has deprived himself of the right to live.

• • • • •

Pius XII reigned in an era bound by a more substantive understanding of evil, an era that called it by its right name, and was deadly serious about it. But by now the word inadmissible is lodged in the papal auto-pen, blotting out fundamental distinction between guiltless victims and willful miscreants. The machete-wielding jihadist, the torturer, strangler, mass murderer, arsonist, and terrorist are now as much objects of concern for the pro-life cause as the unborn.

This is an instance of what Cardinal Gerhard Müller once called a “parody” of the Seamless Garment. Somewhere Joseph Bernardin is smiling.