“Is theology poetry?”

C. S. Lewis asked the question in a 1944 talk to an Oxford debating society called the “Socratic Club.” Nearly two decades later it became the title of one essay published in a collection: They Asked For A Paper (1962).

Does Christian Theology owe its attraction to its power of arousing and satisfying

our imaginations? are those who believe it mistaking aesthetic enjoyment for intellectual assent, or assenting because they enjoy? . . . . if Theology is Poetry, it is not very good poetry.

Why is it not? Lewis’s essay here explains. It is the logic of a scholar of literature and language, an uncommonly literate believer who sets the Christian story against other cosmic belief systems.

What most interests me is not Lewis’s conceptual play, but his visceral response to devotional reading. He was not keen on it:

For my own part I tend to find the doctrinal books often more helpful in devotion than the devotional books, and I rather suspect that the same experience may await many others. I believe that many who find that “nothing happens” when they sit down, or kneel down, to a book of devotion, would find that the heart sings unbidden while they are working their way through a tough bit of theology with a pipe in their teeth and a pencil in their hand.

It cheered me to come upon that passage in Lewis’s introduction to On the Incarnation by St. Athanasius. I tend to avoid devotional writing. Too often the essential subject is the devotee’s own mind—an up-ended narcissism that generates what Thomas Merton termed “the idolatry of devout ideas.”

Often as not, devotional texts serve up pieties by a writer showcasing his aptitude for religious language. Much conventional devotional writing is similar to artwriting [one word]. Both are products created for a susceptible audience. Sentiments are recognizable; the soundness of them, less so.

The Way of the Disciple—an object lesson

Ignatius Press published The Way of the Disciple by Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis in 2003. It was a watershed year in the author’s life. Until then he had been a lay professor of literature and theology at the University of San Francisco, and the father of eight children. In his 2002 preface to the text, he names his children and a woman named Mireiya. Though not identified, she is presumably his wife. The book’s dedication, written in Spanish, acknowledges Our Lady under her title “la Caridad del Cobre, Patrona de Cuba” and extends to “su querida hija mejicana, Mireiya, que mora en mis entrañas” (her beloved Mexican daughter, Mireiya, who dwells in my entrails.)

Publication of the book in 2003 coincided with Erasmo’s entrance into the Trappist order. Ordained ten years later, he is now Fr. Simeon OCSO at St. Joseph’s Abbey in Spencer, MA. His C.V. cites only his professional activity. It omits mention of children or marriage. Biographical explanation of his transformation is hidden behind a cloud of unknowing.

I bought the book because it was the subject of an evening’s discussion in my parish hall.

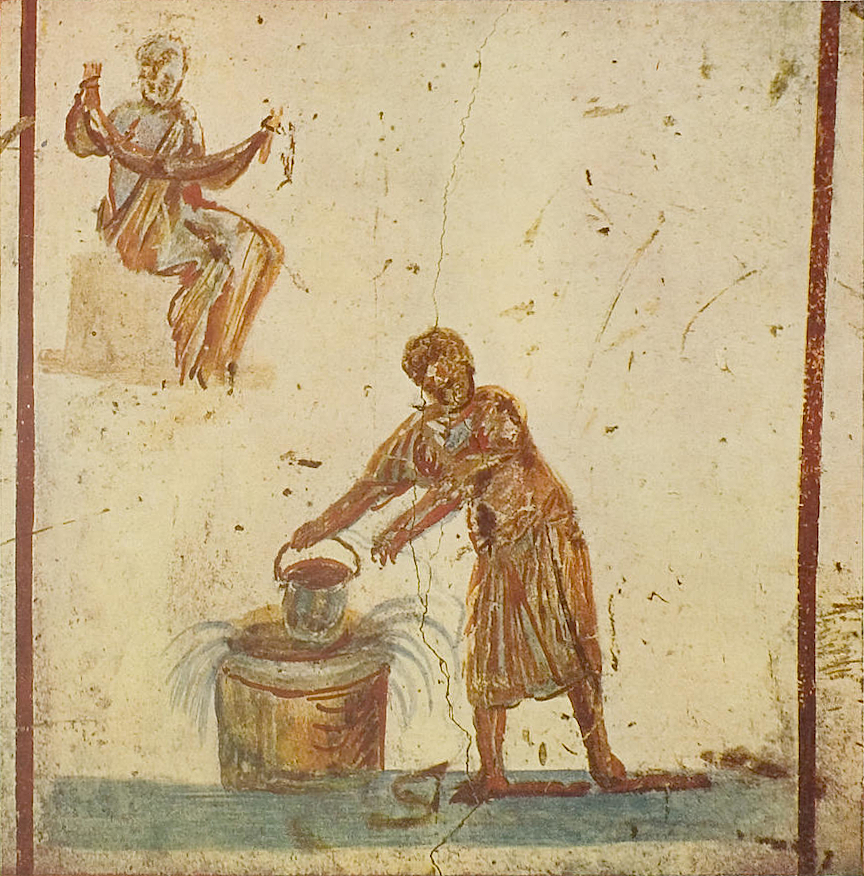

Opening the text at random, my reading began with Erasmo’s ornate meditation on Jesus’s encounter with the Samaritan woman at Jacob’s Well (John 4: 4-42). Fidelity to the motivating drive of John’s gospel—its passion to affirm the messiahship of Jesus—evaporates. In its place is an eroticized vignette of an unbibilical Jesus, more romantic lover than the anointed deliverer of God’s people. The woman at the well is a deceptive anachronism. Like a character in Sex In The City, she has been looking for love in all the wrong places.

[Yes, the Song of Solomon is erotic poetry. But the encounter between lovers is included in the Tenakh—the Hebrew canon—as a metaphor for the relationship between God and Israel, his chosen people. It sings of a corporate embrace, not an individual romance.]

Erasmo intones: “The great moral problem of the Samaritan appears to be that, in her search for love, she has had too many husbands.” Her “frantic search for love” has only created “a greater void in her soul.” The writer cautions against “our tendency to allow ourselves to be seduced by any lover other than God.”

Much is askew here. It is hard to know where to begin. For economy’s sake, start with the woman’s string of men. Erasmo plays the academic game of guessing what the number five “apparently” symbolizes. But any number would suit John’s purpose. The count is a rhetorical device that showcases Jesus’s intuitive grasp of her situation—life with a succession of men.

Given marital laws in theocratic Samaria and Judea, under what circumstances would a woman drift from one man to another? Marriage was a contract between families—in effect, a property transfer. A daughter was passed from parental authority to the jurisdiction of the husband. When a man divorced, he put the wife out of his home, hence outside the sanctuary of his dominion. There was no going back to papa. A divorced woman was a displaced person. She had no home, no income, no familial legal status. Not even her children were her own. All offspring belonged to the husband. (Even a nursling had to be returned to the former husband’s home when it was old enough to leave the breast.)

John’s narrative ignores personal sin. Absent is any call for repentance or gesture of forgiveness. John’s sole concern is right worship and recognition of Jesus as the promised Messiah, the Christ. Better, then, to understand the Samaritan woman in a radically different context—not as an exemplar of wantonness but as a casualty of divorce. Unhoused and impoverished, how would she survive? Sequential male protection, however make-shift, was better than beggary.

The crux of Jesus’s engagement with the woman is the fact that she is a Samaritan—exemplar of an apostate people in the eyes of most Judean Jews. She represents those lost sheep among whom Jesus is destined to fulfill the messianic promise. [“I was sent only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel.” (Matt 15:24)]. Erasmo’s reading of John 4 omits attention to the heart of it—Jesus’s firm assertion of the critical role of Judaism in the history of salvation. (“Salvation is from the Jews.”) And of himself as the consummation of God’s pledge to his own people.

Jews and Samaritans: both believers in the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob

Jews and Samaritans were rivals over the claim of rightful descendants of Jacob. Samaritans held themselves the true keepers of Torah. Judean Jews disagreed. John places his story at Jacob’s Well for symbolic reasons. It is here that Jesus professes a persistent teaching since the days of Abraham: “Salvation is from the Jews.” Jesus declares himself (“I am he . . . “) the realization of the long awaited redeemer. He is the “living water.” The font of salvation.

Such is the shaping reality of the incident at Jacob’s Well. Erasmo reduces it to a banal “flirtation with love.” His subjective mysticism—the Achille’s heal of devotional writers—disfigures John’s reigning purpose: to build faith in the messianic promise. Erasmo conjures up a mystical seduction that delivers the frisson of a bodice-ripper with the magniloquence of nineteenth century French and German literature:

[Jesus] “is wooing her in order to seduce her heart and persuade her to welcome him as the Bridegroom of her soul.” . . . “Jesus has peered into the depths of her soul and revealed to her her own innermost secrets, above all her deep sadness at never having found a true love.”

Erasmo’s interpretive overdrive allegorizes Old Testament bridal imagery beyond its weight bearing capacity. Among Jews, the eroticism of the Song of Songs is understood as an allegory of the bond between God and Israel— his chosen people. For Christians, it makes manifest the love between Christ and his Church. In Judaism and Christianity alike, it is a corporate relationship, not an individual one. Those soaring poetic passages were included in the Tenakh, and later adopted by Christians, to convey the inexpressible, inmost tie between the Creator and the crown of his creation.

Erasmo’s effusion continues: “Jesus has cleansed her soul with his gaze.”

The state of the woman’s soul was not germane to John’s purpose. And of what has she been cleansed? Her life situation has not changed. She is not enjoined to go and sin no more. Nonetheless, there is no stopping a writer enamored of his own emotionalism:

The two have been refreshed by their dialogue of love—he by making himself known and inviting her to intimacy with him, she by opening up little by little to the divine seduction and surrendering at last with all the jubilation and immense relief of an enslaved soul that exits to freedom. . . . She makes herself into a pure instrument of God’s love, now she seems consumed with one desire: to love Jesus and to bring others to him.

Mutual refreshment? Dialogue of love? Seduction? The wording suggests post-coital calm. Interaction between Jesus and the woman shrinks to intimations of psycho-sexual fulfillment. Each one goes away restored—”refreshed”—as if Jesus were as needy of love as was the woman. The passage is scented with the ostentatious interiority of an aspirant to the bestseller list of the Catholic Book Club.

That word seductive is off key. Jesus’s approach might better be described as socratic. As in John’s story of Nicodemus—a pendant piece to the meeting at Jacob’s well—Jesus leads conversation from the literal to the metaphoric. Because she shares the messianic expectation of Jews and Samaritans alike, the woman trusts that the Messiah is coming: “When he comes, he will proclaim all things to us.”

Jesus responds, “I am he, the one who is speaking to you. ”

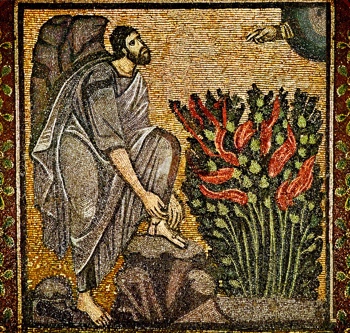

A momentous claim! A prophetic moment! John’s audience would have heard an echo of the great “I Am” from Exodus. When God speaks to Moses from the burning bush, God reveals himself as “I Am Who Am.” When God speaks with the tongue of Jesus, we hear “I Am he—the one who is speaking to you.”

No slouch, the woman catches on. How can she not be stunned? Exhilarated and disquieted at the same time? Thrown into wonder? If this man is, in truth, the expected Messiach, has the messianic age begun? Are we in the end times? It is no surprise that she drops her jug and runs to town. Please, please, come listen to him! So much is at stake! Everything depends on this!

From the Burning Bush to Jacob’s Well

John’s signature refrain, threading throughout the Fourth Gospel, advances God’s revelation to Moses on Mount Sinai. “I am the bread of life.” I am the living water.” “I am the resurrection and the life.” “I am the good shepherd.” “Before Abraham was, I am.”

“But these are written,” John tells us, “that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God; and that believing you may have life in his name” (John 20:31)

I Am Who Am

• • • • •

Jesus was no multiculturalist. The episode at Jacob’s Well culminates in an unapologetic affirmation of the essential role of Judaism in salvation history. Any serious discussion of John 4 has to confront Paul’s words regarding Jews in his letter to the Romans: “For the gifts and the call of God are irrevocable.”

Jacob’s Well anticipates the Good Shepherd discourse: “And I have other sheep that are not of this fold. I must bring them also, and they will listen to my voice. So, there will be one flock, one shepherd’ (John 10:16).

At the heart of John’s gospel is God’s reach for His own. For the lost sheep. Sugared talk of the Samaritan woman’s search for love is an easily digestible detour, readily marketable in a sentimentalized culture.