What does it say about us that more states celebrate Black Friday (the shopping day after Thanksgiving) than Lincoln’s birthday? Or that in eighteen states, Black Friday is a paid holiday for government employees, often in lieu of Columbus Day?

You know yourself what it says. That spares me any need to struggle to keep an upbeat, optimistic tone when I admit that I miss the February 12th acknowledgment of Lincoln’s birthday. Our shiny new Presidents Day is a hollow thing that commemorates nothing. The day comes with a FOR RENT sign hanging from it. Bare and untenanted, it signals a widening vacancy in cultural memory and a loss of commitment to civic solidarity that coheres around remembrance.

This particular birthday, arriving in the midst of a series of televised burlesques calling themselves “debates,” sent me back to authentic ones between Illinois’ incumbent state senator Stephen Douglas and his challenger Abraham Lincoln. I honored the day by keeping myself company with Harold Holzer’s 2004 edition of The Lincoln-Douglas Debates: The First Complete, Unexpurgated Text. Published by Fordham University Press, the book is an effort to disentangle the actual statements made from the copy editing that appeared in highly partisan newspapers the day after each of the seven debates.

The historical archive is a medley of approved—and improved—versions of the actual statements. Holzer writes:

The truth is, what Lincoln and Douglas said at their seven debates in 1858 was not then, nor has it been since, accurately reported. And what was printed has never been seriously questioned, perhaps for the reason, as historian Reinhard Luthin put it, that the Lincoln-Douglas debates have remained “vastly more admired than read.” Or possibly because readers simply remained ignorant of how the record was assembled.

Holzer chronicles the process of assembly whereby the debates were recorded and enhanced by partisan reporters and editors in an effort to showcase their man to the best advantage. The raw power and spontaneity of the speakers were “permanently sanitized.” The whole of it is a fascinating read. Nevertheless, it is not the verbatim reconstruction of the debates that interests me so much as the structure of them. Its severity corresponded to the significance of the issues at stake. Those were debates. Each one lasted three hours, with the first hour assigned to the opening speaker. Then followed an hour and a half for his opponent’s rebuttal. A final half hour was returned to the first speaker for his rejoinder.

By contrast, today’s TV “debates,” with interest centered on personality, and nimble responses to I-gotcha moments, are little more than game shows with candidates competing for a workable image. An opportunity to examine political philosophies dwindles into a media-arbitrated performance. A question thrown to one candidate might not go to another. Slogans stand in for substance. The brass ring goes to the brassiest showboater.

The Lincoln-Douglas debates were not “just” about slavery. They touched deeper issues that continue to inform our politics. Each candidate was awake to the fundamental aspect of matters that would still reverberate when—in Lincoln’s words—”these poor tongues of Judge Stephens and myself shall be silent.” Beliefs about moral governance and a candidate’s relation to the Framers, convictions about the right uses of power and where it resides (in federalization or confederacy of equals? in centralization or subsidiarity?)—all vigorously probed in 1858—are scaled down or omitted for the entertainment of today’s audience at home on the couch.

I love Holzer’s description of the impassioned political climate surrounding the Lincoln-Douglas debates:

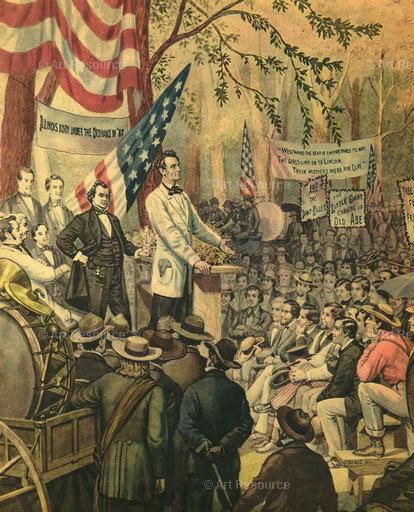

Theirs were not mere political discussions but gala pageants: public spectacles fueled by picnic tables groaning with local fare; emblazoned with gaudy banners and astringently worded broadsides; and echoing with artillery salutes and martial music. On the days the events were staged, roads to debate sites were choked with wagons and horses as whole families crowded onto the scene. Hotels overflowed with guests, and those who could not book rooms slept on sofas in lobbies. . . .

In Ottawa, scene of the first encounter, attendance swelled to more than double the permanent population. They came “by train, by canalboat, by wagon, buggy, and on horseback.” Lincoln arrived on a special train bulging with excited supporters. Douglas led a mile-long procession in a beautifully appointed head carriage, as crowds cheered him “from the sidewalks, from windows, piazzas, house-tops and every available standing point.” At the second encounter, at Freeport, an “immense assemblage” of boosters met Lincoln at the depot, feted him at a levee, and “wheeled” him to the debate site in an open wagon drawn by six white horses. When the debates themselves got under way, one correspondent observed virtual “hand-to-hand conflict for even the meagerest … standing room.”

Once the speeches began, partisans interrupted continually with outbursts of applause and cheering, occasional heckling, and frequent shouts of “Hit him again,” “That’s the Doctrine,” and “Give it to Him.” At one encounter, a heckler shouted out his opinion that Lincoln was a fool, to which he quickly retorted, to gales of laughter: “I guess there are two of us” (an exchange, predictably, expunged from the record later).

The entire series, running from August to mid-October in each of Illinois’ congressional districts, was conducted with great seriousness. However boisterous the chorus of jeers and cheers from huge audiences in open fields, no matter the heat or chill, arguments were conducted in depth with great rigor and gravity. The future of the nation was at stake. And audiences—rough-and-tumble, raucous, impolitic—delighted in following the detailed exchanges. A twenty-first century reader can only envy nineteenth century attention spans.

Both Democrats and Republicans accused each other of “keeping spirits up by pouring spirits down.” Inevitably, the scenes that erupted at the conclusion of each event often rivaled the oratory itself for intensity or humor. The rowdiness could sometimes drift over the edge of acceptability: once, between debates, enemies smeared Douglas’s carriage with what a horrified journalist could only bring himself to describe as “loathsome dirt,” referring undoubtedly to excrement. And on another occasion, Lincoln was unexpectedly borne off by exuberant supporters who failed to calculate their candidate’s extreme height, leaving Lincoln’s legs dangling unceremoniously “and his pantaloons pulled up so as to expose his underwear almost to his knees.”

It was not unusual—even after standing on their feet much of the day for the festivities, either denied sufficient food and drink or bloated with an excess of both—for such overwrought partisans to flock to nearby locations once debates ended for still more boisterous celebrations, and sometimes more speeches as well. (Lincoln himself joined an audience after the first debate to hear yet another politician deliver yet another oration.) Even after the orators (and their listeners) were finally exhausted, the townspeople would invariably be kept awake all night by noisy, torchlit parades through the streets.

The carnival spirit of throngs of listeners signaled the intensity of public engagement with the issues. Voter turn-out for that state senate seat was enormous. Lincoln lost to Stephens. For all the eloquence in his own written speeches, he was uncomfortable speaking extemporaneously. And was often not effective on the stump.

But we know how the saga ends. And we have more than an inkling of what has been lost in setting aside commemoration of the sixteenth President of the United States.