Is papal art appreciation all that it seems?

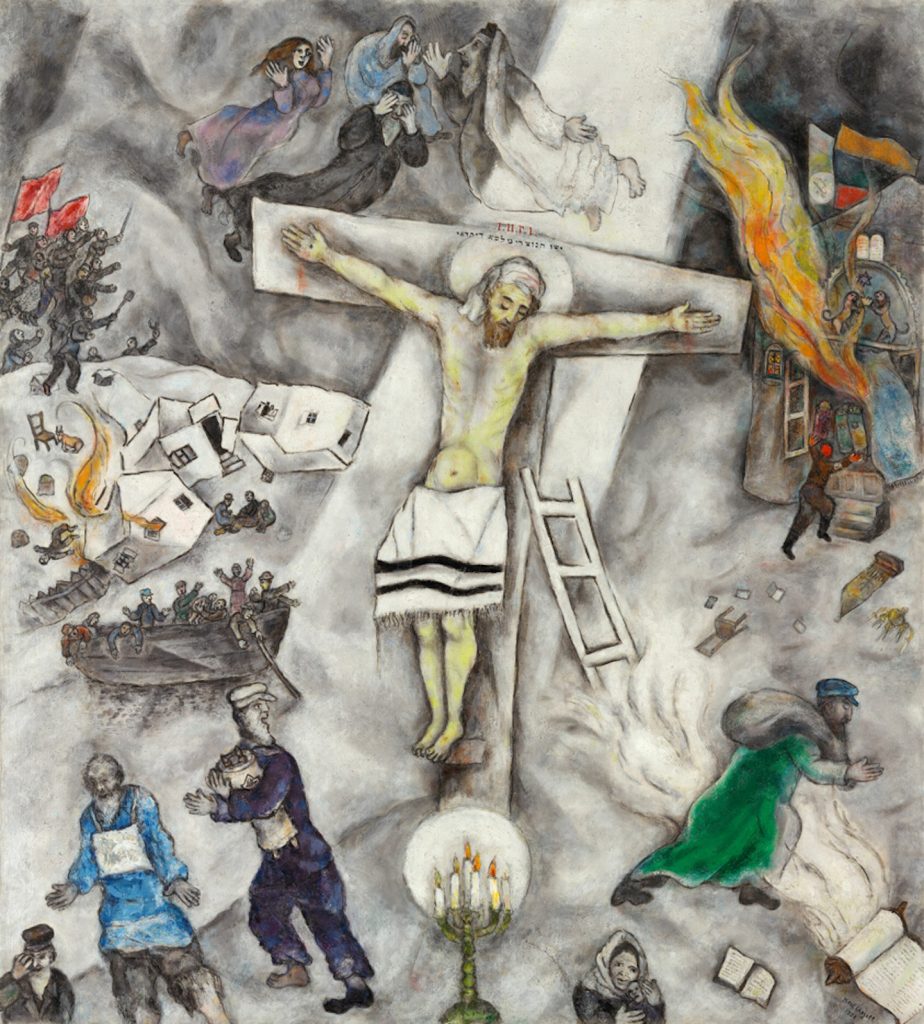

Pope Francis once cited Chagall’s “White Crucifixion” as one of his two favorite paintings. Perhaps he really meant it. Or maybe his stated preference was a cost-free instance of diplospeak. A polite ceremonial gesture to cover an entrenched imbalance in his Middle East sympathies? Either way, as an expression of sympathy for the Jewish people, papal art appreciation is easy but insubstantial.

It is no substitute for unambiguous support for Israel, a tiny Jewish state targeted for extinction from the date of its founding. To Israel’s dismay, Francis rushed to use the term “State of Palestine” in 2014, five years ahead of the UN. He hailed Mahmoud Abbas—who vowed never to recognize Israel’s legitimate claims to nationhood— as “an angel of peace.” Francis’ greater solicitude for the Palestinian cause announced itself in 2020 by refusing to recognize the Abraham Accords as a realistic step toward peace in the Middle East.

This past November, Francis affirmed his longstanding commitment to the frayed Two-State Solution, a shopworn tenet of the endless “peace process.” But how can this devoutly-to-be-wish’d consummation be realized if the Palestinian “state”—home to genocidal Hamas and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad—is committed to erasing Israel off the map? Where is the sanity of an arranged “peace” between two sovereign bodies if one of the pair is pledged to the annihilation of the hated other?

Diplomacy has a shelf life. History mocks the careless who skip the lesson. Often as not, peace has to be imposed. At some point in an ongoing conflict, one side has to win. Principled people are compelled to choose sides. This, in full grasp of the tragic potential of necessary choices. Pity the population of Israel—Arab and Jew alike—if the wrong side wins in this by-now mislabeled “peace process.” Francis has thrown papal weight behind it as the only framework of justice in the region.

The Vatican gave a thumbs-up to the 1978 Camp David Accords. It cheered the 1993 Oslo Accords. Yet it kept mum on the Abraham Accords, reached in August, 2020. Silence covered an ignoble refusal to acknowledge an historic achievement in large part because it benefited the re-election chances of Donald Trump. According to Francis’ apologists, the dog did not bark because these latest accords did not give the Palestinian state its perceived due. Papal distaste for Trump—together with open preference for the corrupt and compromised Biden—overrode an available effort toward Middle East peace.

Sanctimonious world-improvers have a gift for advancing high-minded excuses for lower-minded motives.

Chagall and the Bolsheviks

Stay another moment with White Crucifixion. Note the troop rushing in from the upper left of the canvas. They carry red flags. Are these Nazis, or the Red Army? Insignia on the flags is a blur but the colors—red and yellow—are those of the Bolshevik-led Red Guards. No hint appears of the Nazi device: a black swastika within a white circle. The flag-wavers are most often interpreted as a Nazi mob. More likely, though, the sketch alludes to the Bolsheviks, welcomed by Chagall as liberators of Russian Jews from tsarist restrictions.

In the early years of Lenin’s rise, Chagall’s sympathies were enthusiastically Red. After leaving Paris in 1914, he returned to Vitebsk, where he joined Lenin’s Council of People’s Commissars. Appointed Commissar of Arts in Vitebsk, he designed colorful banners celebrating the first anniversary of the October Revolution. They festooned the streets of Vitebsk in 1918.

A year later, he established The People’s Art School, hiring Kazimir Malevich, a charismatic theorist of non-objective art, and El Lissitzky. Aesthetic disagreements with his chosen faculty plagued the school from its launch. Discontented, Chagall moved to Moscow later in the same year. He left Russia for good in 1922, moving first to Berlin then back to Paris.

Taking into account his view of himself as an artist, he wrote: “I think the Revolution could be a great thing if it retained its respect for what is other and different.” The Revolution (1937), painted one year before White Crucifixion, depicts the same flag. Marcchagall.net explains this way:

To the left, revolutionaries are seen rushing the barricades, their red flags proudly proclaiming the victory of Communism. To the right, this image of unity, standing for political demands for equality, is counter-balanced by the free play of the human imagination. We see musicians, clowns and animals playing, the customary loving couple are lolling on the roof of a wooden hut, and in typical Chagall style, the force of gravity has been suspended so that the ubiquitous energies may develop freely. The figure of Lenin links the two zones; balanced acrobatically on one hand, he is showing the revolutionaries the true way to a world of individuality. [My emphasis.]

The year 1937 seems rather late for depicting Lenin as an edifying guide to Chagall’s belief that “The creative power of the individual is the driving force in the struggle for political liberty.”