Born Moiche Zakharovitch Chagalov, Chagall never resolved his conflict between affinity for Yiddish culture and ambition to mark his place in the timeline of modern Western art. The tension took a toll on his instinct for painting. But let us not begin there.

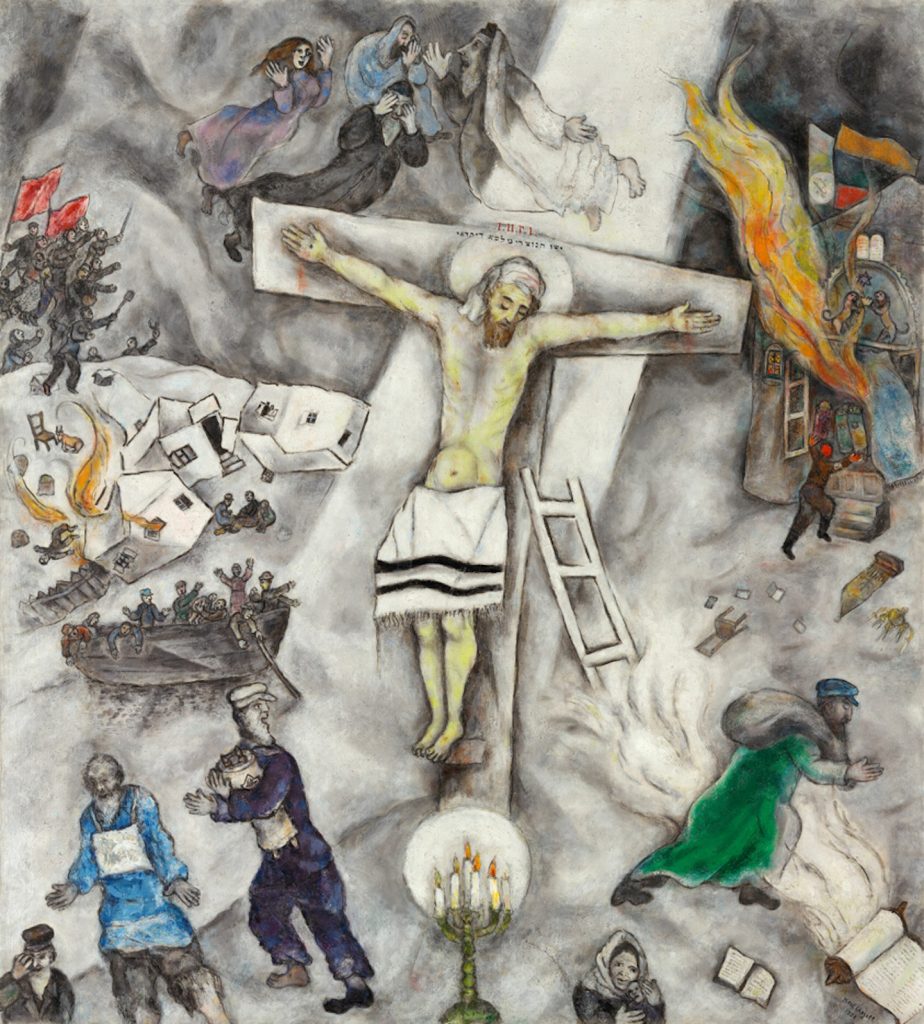

Better to start with Brad Miner’s essay “Marc Chagall’s Jesus,” for The Catholic Thing. It distills the reasons why Chagall’s work continues to resonate. And it provides context for “White Crucifixion” (1938), the best known of Chagall’s many interpretations of the crucifixion theme:

Chagall was living [for a second time] in Paris at this point, and news of the Kristallnacht pogrom and other attacks on Jews were the impetus for the creation of “White Crucifixion.”

On Kristallnacht, or the Night of Broken Glass, November 9-10, 1938, thousands of Jewish stores, homes, hospitals, and synagogues had been attacked by the Nazi paramilitary group, Sturmabteilung (SA or Storm Troopers). About 30,000 Jewish men had been arrested and sent to the camps.

By transplanting the site of his crucifixions to the shtetl in Vitebsk, his birthplace in present-day Belarus, Chagall signals their interpretation. The corpus draped in a tallit is not the individual Christ of Christianity. It is European Jewry. As he wrote: “For me, Christ has always symbolized the true type of the Jewish martyr. That is how I understood him in 1908 when I used this figure for the first time… It was under the influence of the pogroms,”

Miner quotes a 1991 essay by Ziva Amishai-Maisels for Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies. A Brooklyn-born art historian on faculty at Hebrew University, Jerusalem, she wrote that Chagall “emphasized Jesus’s importance to both Christians and Jews, for the Jewish Jesus with his covered head and his fringed garment is also a Christian.”

Contra the art historian. . .

It is odd wording from a scholar. Jesus was not a Christian. Neither was St. Paul, Jesus’ first expositor. Both were observant Jews. Christianity, as such, did not yet exist. Chagall’s interest in a murdered rabbi from Nazareth had nothing to do with Jesus in the concrete. Nor with Christianity. Interest was strictly emblematic and pictorial. Chagall’s crucified figure was never the Jesus of Christian belief. Rather, it was a personification of the Jewish people’s long history of travail. In André Breton’s phrase, it was “an embodied metaphor.” Sustained by popular sympathies, the metaphor frequently triumphed over the visual work.

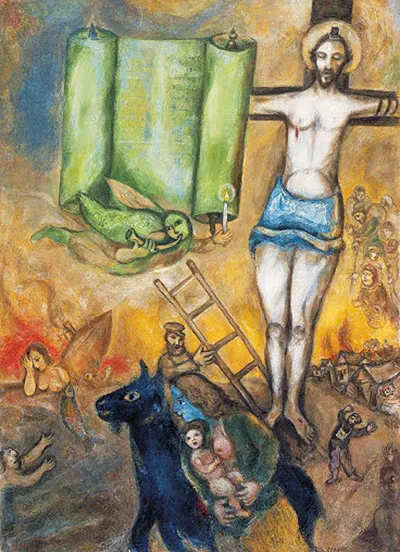

From his youth in the shtetl of Vitabsk, Chagall viewed the Crucifixion as “a symbol of Jewish suffering.” His artistic relation as a Jew to a Western, hence Christian, canon held Chagall’s imagination throughout his career. His first Crucifixion was created in 1908, two years after the czarist pogroms of 1903-06. The rise of Nazism in the Thirties lent his later handling of the motif an inescapable soci0-political resonance. That chord shaped public acclaim for work that sometimes failed its own theme.

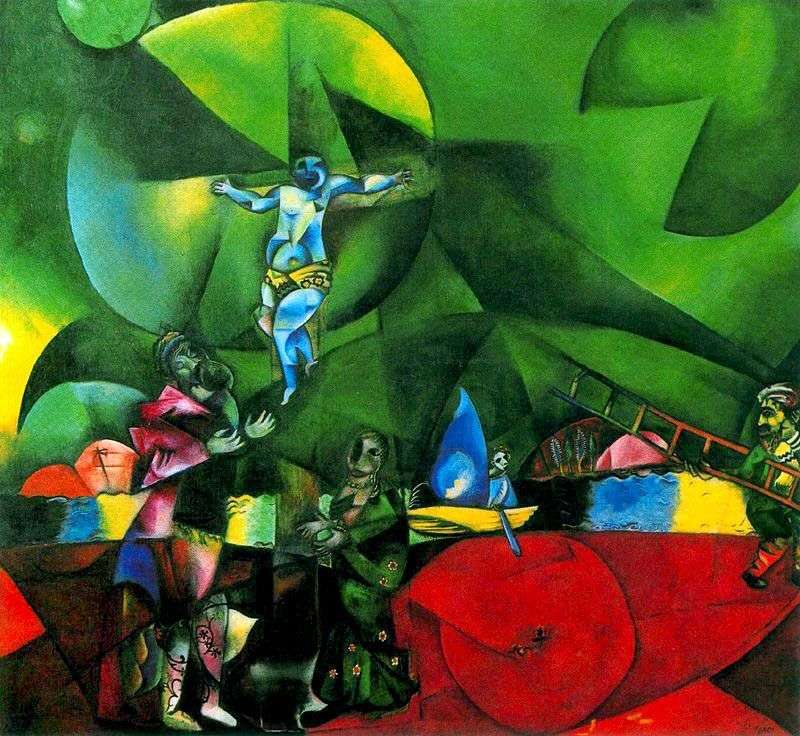

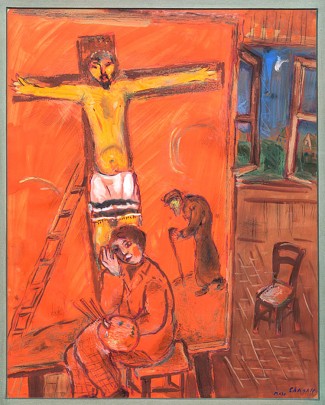

To illustrate, consider the following two paintings. The first, “Golgotha” (1912) uses the Crucifixion as a ready-made device for an experiment in Cubist composition, a stylistic revolution of the era. The next, “Apocalypse in Lilac, Capriccio” (1945) is a small, hasty gouache made during his years of sanctuary in New York State. Here the Crucifixion dwindles to a sketchy, formulaic expressionist exercise. Expressionism was another of the stylistic rebellions against traditional depiction that captured Chagall’s attention. [ The term capriccio traditionally applies to architectural fantasies, e.g. ruins or other archeological inventions, in a fictional landscape painting.]

Chagall adopted the cross, Christianity’s uttermost symbol, as a venture in iconography. Pictorial enterprise—graphic and coloristic daring—animated the avant-garde circle of early Modernist painters he joined when he arrived in Paris in 1910. It was the first of several sojourns in France. Frenchifying his name, he took as his own a quintessential motif of Western art. The Post-Impressionists—most notably Gauguin—had done just that decades earlier. Joined to sociopolitical impulses, Chagall’s appropriation of the Crucifixion motif was a means to lay claim to the monumental Western canon. It provided entry to an artist seeking to establish himself within that canon while simultaneously maintaining a parallel distance from it.

Chagall was not necessarily a practicing Jew. Neither was he, as Miner rightly notes, a crypto-Christian. Raised in a devout family, his Hasidic roots stamped his identity and pictorial imagination. Though he painted some one hundred crucifixions—several commissioned—Jesus was never his subject. Jews were. They were historic scapegoats for a world that did not want to hear the Shema: “Hear, O Israel, the LORD our God is one.” As far back as the pharaohs, that declaration of allegiance to the kingship of the one true God was disruptive in a world enshrined to multiple gods and their established agents.

The Jesus of culture vs. the Jesus of faith

Chagall’s work resonates on a cultural plane separate from politics and detached from religious conviction. There is no clearer statement of that plane than what appears in Samuel Sandmel’s We Jews And Jesus (1965):

The figure of Jesus is part of Western culture, and I hold myself in all truth to be a legatee of and a participant in Western Culture. In this sense, the figure of Jesus comes into my ken inevitably, just as he comes into the ken of all Western Jews. . . . I see no valid reason for Jews to insulate themselves from the Jesus of Western culture, any more than they should, or would, from Plato.

Rabbi Sandmel, an authority on early Christianity, was sympathetic to the tension between the Jesus of Western art and the Jesus of Christian belief. He wrote:

I am saying that because Jesus occupies a position in Western culture, and since Jews in the West are part of Western culture, Jews will inevitably encounter his figure. Jews need not shy away from such cultural encounter.

. . . I am eternally grateful to live in a land and in an age in which I am not constrained, through having felt the hostility of Christians, to cut myself off from that place in Western culture which Jesus occupies. Near Jerusalem there is a Byzantine church to which Israelis go in great numbers to hear organ recitals of Bach. They do no cut themselves off from the great music of Western Civilization.

It was in the Byzantine churches of Vitebsk, a city close to the Russian border, that Moiche Zakharovitch Chagalov discovered icons—what Pavel Florensky called “the structure of dreams”— and images of the Crucifixion.

[To be continued]