With liturgical regularity, Christmastide brings the magic of The Nutcracker. This is the perfect season for it. By December, the year’s worth of adult disdain for all things enchanted has reached a crescendo. “No, Virginia, you’ve been had,” galumph uncomprehending gradgrinds who dismiss fantasy as lying. Childhood’s sensitivity to wonder is put to the test this time of year. Children are made to suffer obtuse grown-ups who refuse to believe that toys come alive, that mice have queens, or have forgotten that nightmares, too, have their bewitchments.

We owe The Nutcracker to Ernest Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann, celebrated among the German Romantics of his day. As much a changeling in careers as in name, he was born Ernst Theodor Wilhelm Hoffmann in Königsberg, Prussia, in 1776. Sometime in his thirty-seventh year, he changed his middle name in honor of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Though he continued to use Wilhelm on official documents, he wrote and composed under the name E. T. A. Hoffmann.

Hoffmann had a variegated career as a stage manager, musician, music critic, librettist, artist, and, early on, a law officer in the Prussian army. He wrote and staged a ballet of his own, Arlequin, in 1816, the year in which he wrote what would later become the basis of The Nutcracker. To the extent that we remember him today at all, we are most familiar with his name as the writer of short stories. He was the fictionalized protagonist of Jacques Offenbach’s opera The Tales of Hoffmann, based on three Hoffmann fables.

Awake to the singular and inexplicable, Hoffmann disliked that breed of rationalists incapable of recognizing even the demonic. He intended The Nutcracker and the Mouse King as an unsettling novella for adults, not children. His seven-headed Mouse King is easily recognizable as a märchen variant of the Beast of the Apocalypse so famously depicted by Dürer. (The Nutcracker ballet, first performed in St. Petersburg, in 1892, to Tschaikovsky’s music, is based on Alexander Dumas père’s later and lighter adaptation of the tale.)

Hoffman created the story in opposition to what he saw as the Enlightenment’s assault on the imagination. He championed intimations of the extramundane, those veiled realms of the empirically unverifiable. A poet in words, music, and line, he defended the authenticity of realities existing outside the scientific world view.

This passage from Hoffmann’s “The Perfect Stage Manager” is a sly guide to his aesthetic objectives:

If perhaps you have not already noticed it yourselves, I will herewith reveal to you that the poets and musicians are in an extremely dangerous league against the audience. For their aim is nothing less than to drive the spectator out of the real world where he is so well off . . . when they have completely separated him from everything that he previously knew and liked, to torment him with all possible emotions and passions extremely prejudicial to his health.

As preface to his astute review of the score of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, Hoffmann wrote that music “reveals an unknown kingdom to mankind: a world that has nothing in common with the outward, material world that surrounds it, and in which we leave behind all predetermined conceptual feelings in order to give ourselves up to the inexpressible.” Doing so, we enter the dark.

Shortly before Christmas this year, The New York Times permitted itself a guest appearance by Eric Kaplan, author of Does Santa Exist? A heavy thinker, Kaplan explains what it would take to induce belief in Santa: “Maybe I could take psilocybin and have a group of my friends chant, ‘Santa exists!

Santa exists!’ while I am tripping my brains out.” He arrives at a boilerplate insight exquisitely fit for threadbare times: “Each belief is the beginning of a voyage of self-discovery.”

Poor Kaplan. The dolt has it backwards. Any Sugar Plum Fairy could tell him that self discovery has nothing to do with it. Not with belief, and certainly not with art. Hoffmann understood that true artistry originates in those ineffable modes of self transcendence that accompany genuine struggle to create. To believe.

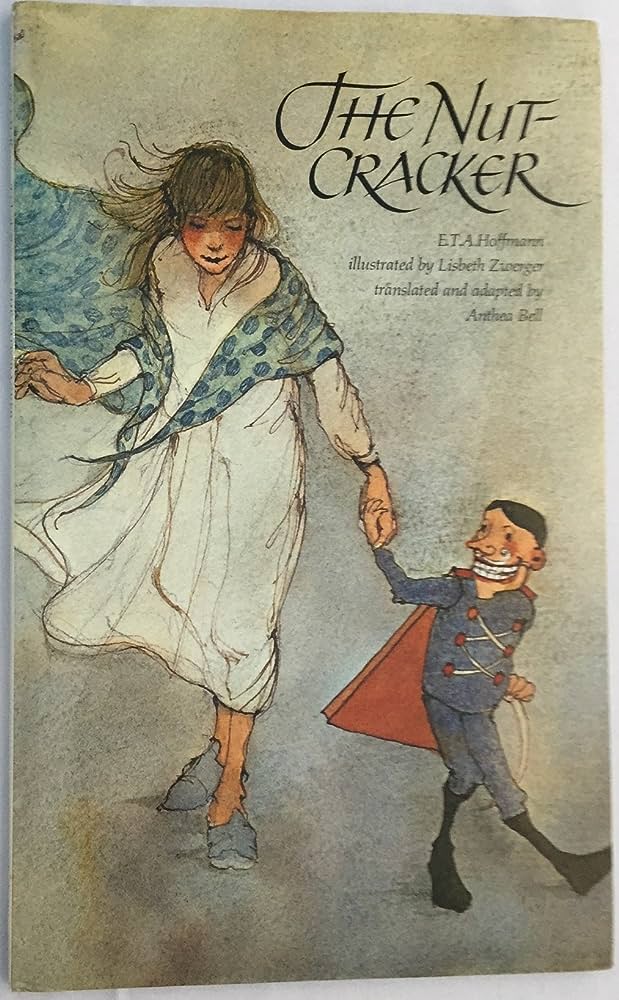

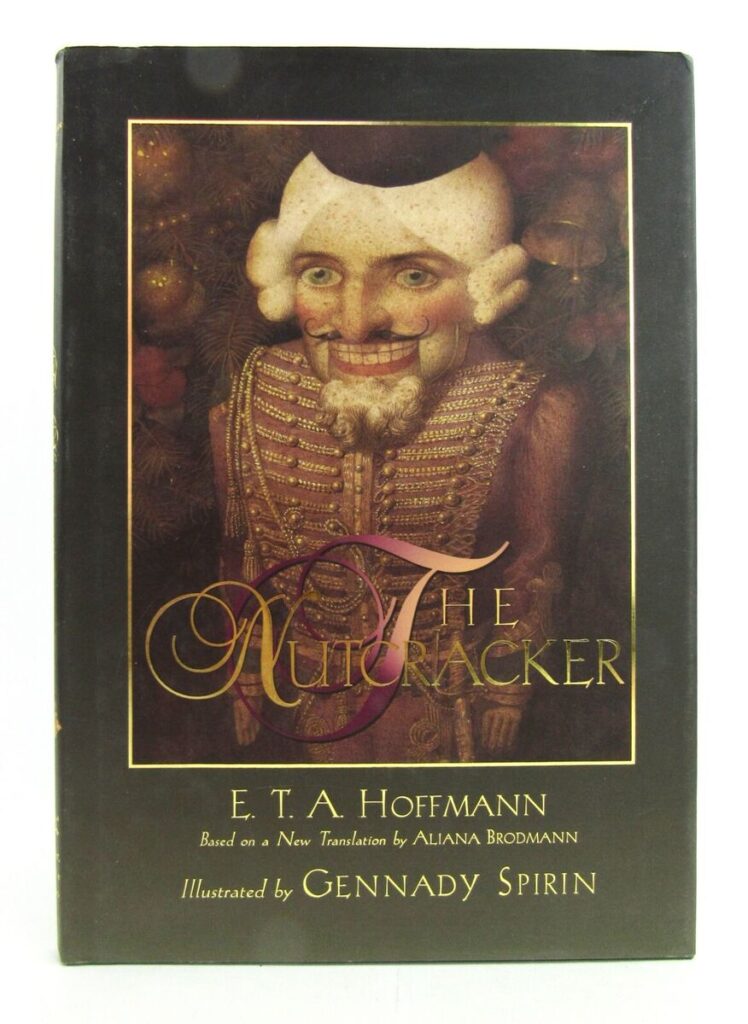

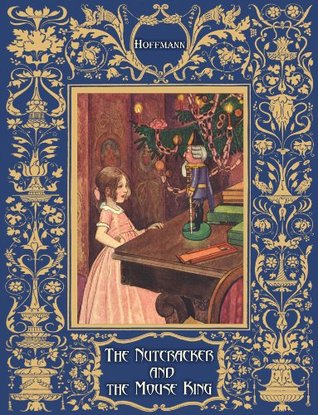

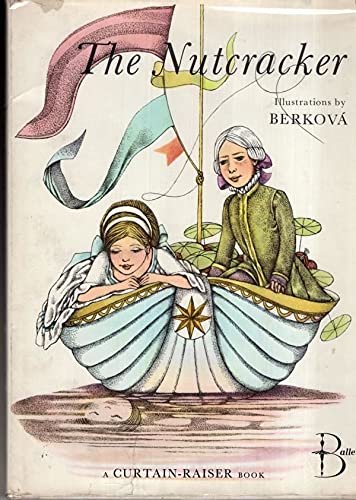

Before the season ends, try to spend some time with E.T.A. Hoffmann and The Nutcracker. Althea Bell’s translation is lovely, still available as a used book. Any edition with illustrations by Gennady Spirin, Dagmar Berkova, or—a favorite—Artus Scheiner will get you through the humbug of the coming year. The edition with Maurice Sendak’s lively illustrations is everywhere but not nearly as captivating as others for lovers of book arts.