The Society of Jesus explains the recent launch of a West Coast province under the headline: “The Dawning Of Jesuits West.” The caption is too suggestive to have been inadvertent. So let us take the Jesuits at their word and run with the allusion.

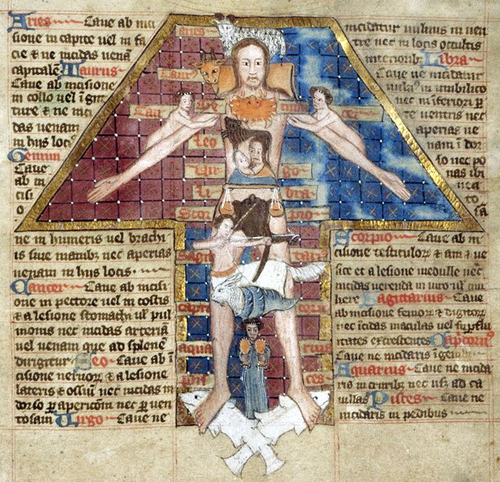

This glistening new province hints at itself as the final coming of the Age of Aquarius. That grand epoch of astrological hope is really on its way this time ‘round. Peace will guide the planets and love will steer the stars. Jesus, avatar of Western civ, earns a perfunctory shout out. But reserve applause, please, for these sons of the higher discernment who let the sunshine in by singing from the Social Action Handbook.

Their lyrics go like this:

We are hope-filled Catholicism. . . .

We are globalists and ecologists.

We speak up for the voiceless.

We defend immigrant rights.

We welcome immigrants and refugees.

We know the gravity of climate change.

We serve all religions, ethnicities, and genders.

We encourage pluralistic values, multiple values.

We are a multicultural family.

We invite the stranger in.Refrain:

We are contemplation in action.

We are a force for good.

We are Jesuits West.

On it goes, messianic pretension in a minor key. Such is the burden of this self-admiring video from Loyola Productions advertising Jesuits West which burst upon ten Western states “and beyond” on July 1. The venture re-unites the California and Oregon provinces that split in 1932.

That old quip—the Sixties, like poverty, will be with us always—proved prophetic. The defining spirit of the Sixties has spread like an intestinal parasite, feeding off its hosts and weakening their immune systems. Judging by their marketing promo, the Jesuits have succumbed to undying New Age bugs: paper-crane peace, universal harmony, and we-are-the-world enlightenment. The video makes plain that the agents of Aquarius Rising are the doubly-ordained preachers of today’s multicultural, open-borders catechism. Everyone on camera is fluorescent with amour propre.

Sanctimony suffocates. The schicht reminded me of my lifelong distaste for Walt Whitman’s cosmic conceits. The old bard gave Loyola Productions its anthem:

I celebrate myself, and sing myself.

And what I assume you shall assume.

Just so. Here are west coast Jesuits, and their lay associates, eulogizing themselves for their enlightened advocacy of every progressive trope embraced by Hollywood, the media, and academia. Their collective egotism admits no moral responsibility for the tinderbox of political and social repercussions of action by such bodies as the Loyola Immigrant Justice Clinic. Or the Association of Jesuit Colleges and Universities that lobbies on behalf of “undocumented students” and “every faith tradition.” (That last, a cloaked euphemism for Islam.)

The Interesting Poor and the Boring Poor

Ray Allender, S.J., pastor of San Francisco’s first sanctuary church, offers a self-congratulatory apologia for frustrating immigration rules. Over the entry doors of St. Agnes hangs a grand sign: WELCOME IMMIGRANTS & REFUGEES. Fr. Allender explains that “in life so many issues are gray” but not the issue of illegal aliens the undocumented. To him that was easily “a black-and-white issue.” No complicating considerations. Not a one. Rule of law does not inhibit the thinking of men who draw moral income from opposition to what they perceive as bourgeois ordinances. Fr. Allender simply “had to be there” for the self-imported masses who jumped the lawful queue. Whether their numbers and predispositions undermine the common good—something that implies a shared cultural heritage—is not his concern.

Missing from the promo’s parade of pieties is any recognition of the nation’s existing poor. White poor are noticeably absent. However needy and marginalized they might be in real life, whites are not among the Interesting Marginalized, a conceptual class. Only those who serve preferred ideological purposes—among them, the mantra of diversity—are docketed for attention.

There are, for instance, Appalachian towns without power or running water in regions with some 40% of the population living below the poverty line. California has its own cities, like Fresno and San Bernadino, with high poverty rates among citizens both white and black. Meanwhile, Latin American illegals enjoy a protected status regardless of conditions in their home country.

One haunting Johannine passage reverberates here: “I know mine and mine know me.” I cannot help wondering: Have Jesuits chosen against their own?

Third World enthusiasts—what else to call these people?—are not vexed by the impact of their paternalism on the economic vulnerability of low-skilled and uneducated native-born Americans. Rural Maine or the Mississippi Delta are not as newsworthy as the U.S.-Mexican border where Jesuits radiate a “humane presence” with their Kino Border Initiative.

Compassion as Self-Regard

In a culture susceptible to images, newsworthiness is a seductive illusion. Jesuits and their partners appear in the grip of it. By the end of this video, you wonder why no one on camera signaled interest in the means of reducing or eliminating poverty. Accent is on managing it. Come cataclysm, our managerial elite—Jesuits among other NGOs—will be there to manipulate and administer it.

A sophisticated publicity project, the video marries the Human Potential Movement (another Sixties product) to the Social Gospel:

We give the thirsty something to drink. We help people connect with silence to help them become more fully themselves, more fully alive.

Reigning clichés of the religious left meld with those of the academic left to prepare young adults “to go into the world to make a difference.” What, specifically, is the nature of that difference? Which avenues of study best equip young people to fathom the world they presume to address? Hard to tell. What matters are “more scholarships, and more social justice,” the latter determined by bien pensant credos.

Newly christened as undocumented immigrants, illegals put flesh on that solemn abstraction, The Oppressed. By virtue of their symbolic role, illegals are the designated recipients of material and political largesse offered in disregard of the fragility of civic culture and the limits of national resources. Jesuits West embraces a model of accommodation that requires the country to welcome anyone who wants to come (168 million, according to a 2009 Gallup poll) without requiring anything in return. It is a one-way street, a sacrificial model—”pure oblation” in Pascal Bruckner’s words—that confuses heroic individual martyrdom with societal suicide.

To a considerable degree, what the Noble Savage represented to bohemian litterateurs of the Romantic era, illegal aliens represent to the religious left in our own day. Liberated from original sin by their assigned victim status, they stand in blameless witness against the flawed ideals of an affluent consumer society. Like Diogenes in his rags on the streets of Athens, they are a living j’accuse to what self-appointed paladins consider a guilty civilization. The more of them—the sacralized Stranger— the nation admits, the closer a stained society inches toward redemption. Or so the libretto reads.

Secular Education Packaged in a Religious Idiom

In what sounds like a plea to keep Pell Grants coming, Paul Hogan, principal of Portland’s Jesuit High, announces: “All students should have access to a Jesuit education.” This is the language of entitlement in disguise, a sidling way of stating that all students have a right to a Jesuit education.

Yet Loyola Productions leaves viewers wondering precisely what a Jesuit education achieves beyond a taste for political activism of a leftist kind. The video proclaims the corporal works of mercy, to which all Christians are called. But pursuit of them here is handicapped by a partisan stance that funnels pity toward politicized ends, ones that remain debatable among conscientious Catholics.

After assimilating religion to politics, what is left of faith? Catholic education is drained of meaning if affirmation of the divine is mortgaged to advocacy for one political strategy over another.

• • • •

I remember the words of Jean Cardinal Daniélou: “A man without adoration is a mutilated man.” Doubtless, adoration and education in those things not of this world have not been forgotten by Jesuits. But they have been put in their place, quietly sidelined in favor of the propaganda of social justice—an idol of the age worshiped on any contemporary secular campus.