It is August. This is the time of year to loll in a hammock, take bribes, and be fanned by eunuchs. But I have no hammock. No one is coming forward with a bribe. And all the eunuchs are clustered where they have always been—in high places, far from here and out of reach. Still, I can dream.

In reality, there is no alternative to getting on with the job. This time, though, hot weather gives me a plausible excuse to put aside a proper essay and just . . . well, blog a bit. Natter in small bites. An amuse-bouche or two. The hit-or-miss of things. Those random bits and pieces that would beckon more words if the days were cooler.

Start with one of Mary Howitt’s moral tales for children.

I take particular particular delight in running into a fellow Catholic in unexpected places. Earlier this summer, and curious about the full lyrics to that old story-poem “The Spider and The Fly,” I happened on Mary Howitt, née Botham. Born into a strict English Quaker family in 1799, she died a Roman Catholic in 1888. Nothing is certain about the date of her conversion, only that it occurred late in life.

She went over to the Church of Rome out of affection for Pope Leo XIII. Little more than that tidbit is known. Still, it easy to see the appeal of Leo’s pontificate to a sensitive, conscientious woman who had been an abolitionist in her youth and became a suffragette in later years. Howitt would have shared Leo’s concern for the condition of the working class and the dignity of the individual. Perhaps Leo’s Marian piety also appealed in a similar way.

Add, too, her having lived in Rome from 1871 until her death. Cultivated Italian urbanity and a Roman setting must have exerted a strong pull on a woman who had chafed from youth against the austerities and limited-palette preferences of the Society of Friends. Her long passeggiata from Clapton and St. John’s Wood to the Piazza Navona and the gardens of the Villa Borghese was a migration toward enchantment.

Bartleby.com, citing a biographical essay published in 1907, offers this:

She herself declared that she was devoted to the Pope, and not to the papacy, and indeed, stronger personal influences may well have been operative than we know for certain.

That same essay describes Howitt as “one of the most graceful, versatile and voluminous writers of the earlier half of the century.” Neighbor to Alfred Tennyson, she produced some 180 books and was intimate with the literary circles of her day. Together with her writer/editor husband William Howitt, she mingled with Charles Dickens, and William and Mary Wordsworth, among other luminaries. She translated the early stories of her friend Hans Christian Andersen.

Howitt’s name is largely forgotten. But still lingering in cultural memory is her splendid moral tale of a predatory spider and a vain, suggestible fly. A female, wouldn’t you know.

The first line of conversation between the sly villain and his victim is classic. The rest, delicious:

“Will you walk into my parlor?” said the spider to the fly;

“‘Tis the prettiest little parlor that ever you did spy.

The way into my parlor is up a winding stair,

And I have many pretty things to show when you are there.”

“O no, no,” said the little fly, “To ask me is in vain,

For who goes up your winding stair can ne’er come down again.

Seduction progresses for another five verses. The silver-tongued spider is a master of honeyed words:

“Sweet creature!” said the spider, “You’re witty and you’re wise!

How handsome are your gauzy wings, how brilliant are your eyes!

I have a little looking-glass upon my parlor shelf,

If you’ll step in one moment, dear, you shall behold yourself.”

“I thank you, gentle sir,” she said, “for what you’re pleased to say,

And bidding you good-morning now, I’ll call another day.”

You begin to root for the fly. Keep your distance, girl! Hold firm! But in another verse or two the silly little thing succumbs to ingratiating soft-soap. Just as the practiced spider knew she would. Poised for conquest, “he set his table ready to dine upon the fly.” Pleased for an opportunity to display her charms, the fly lets down her guard.

With buzzing wings she hung aloft, then near and nearer drew

Thinking only of her brilliant eyes, and green and purple hue;

Thinking only of her crested head — poor foolish thing!

She flits too close to her nemesis. The spider leaps. She ne’er is seen again.

And now, dear little children, who may this story read,

To idle, silly, flattering words, I pray you ne’er give heed;

Unto an evil counselor close heart, and ear, and eye,

And take a lesson from this tale of the Spider and the Fly.

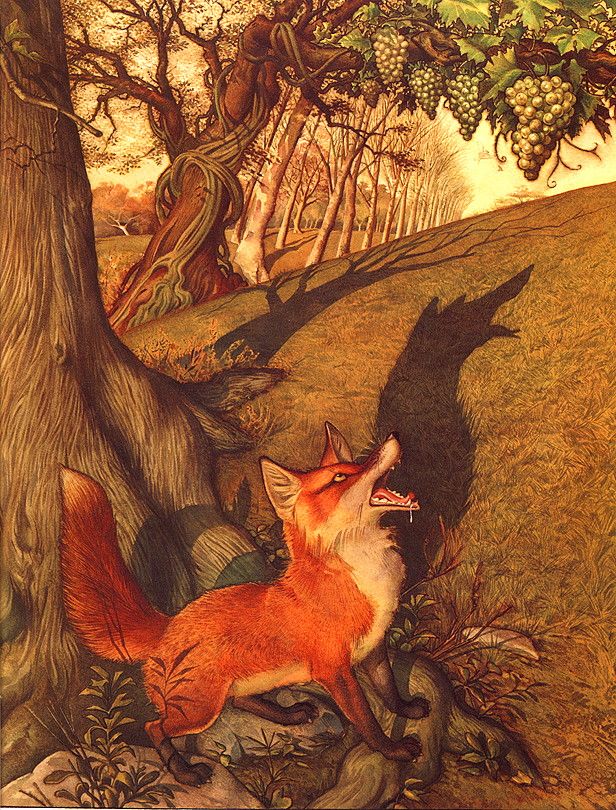

An ancient tutor to the young, the animal fable has persisted more than two and a half millennia since Aesop. Chaucer’s Wife of Bath, in the prologue to her tale, makes brief allusion to “The Lion and the Man,” a fable traditionally attributed to Aesop. Howitt’s verse fable descends from Aesop’s “The Fox and the Crow.” Horace made mention of the same tale in the first century BC; La Fontaine interpreted it for the 17th century.

In our own century, the metaphoric universe of this hortatory genre is waning, losing ground to other adult agendas. The idea that children need instruction in the virtues and the consequences that flow from lack of them seems quaint these days. Formation of character is displaced by the formation of correct attitudes toward designated issues. (No need to list them. You know them all.) Still, at the end of the day, character counts.

It counts because deceptive counselors are everywhere and always. They roam the world seeking susceptible souls. They vest themselves in all kinds of wardrobes, and beguile in a range of engaging tones. Impressive-sounding, they are a ruinous bunch. Very likely you could name a few.

And just as likely you are asking yourself: If Mary Howitt were alive today, would she be drawn—like her own pliant fly—to the current pope? Would she flutter into his parlor of illusions and facile mercies? There is no way to know. We can only wonder.

• • • •

Tony M. DiTerlizzi’s 2002 images for Howitt’s cautionary tale, rendered in black and white, earned its Caldecott Medal. Between the monochrome and the costuming, the pictures have the feel of stills from a silent movie. DiTerlizzi gave a 1920s accent to this fatal persuasion. His fly is a flapper in a cloche hat—Gatsby’s Daisy Buchanan wandering away from a party on West Egg. His spider comes tailored like Béla Lugosi’s Count Dracula. Those spats! The cape and cravat! The high wing tip collar! Bram Stoker applauds.

• • • •

Or he might have back in 2002, fifteen years ago. Since then, our common culture—that shared stock of fertile references— has been shrinking faster than Alice after she swigged from a bottle marked DRINK ME. What place have Aesopian fables, with their charm and insight into fundamental truths about human nature, in today’s culture of childhood? Without an Instagram or Facebook account, does Aesop and his tribe still exist? Kids on Snapchat do not need to carry a book.

It chills me to see children sitting next to their parents, each generation scanning its own devices. Is the modern child learning what it means to be human more from social media than from the longue durée of inherited modes of discernment? Authority driven by algorithms and popularity diminishes adulthood and childhood alike.

• • • •

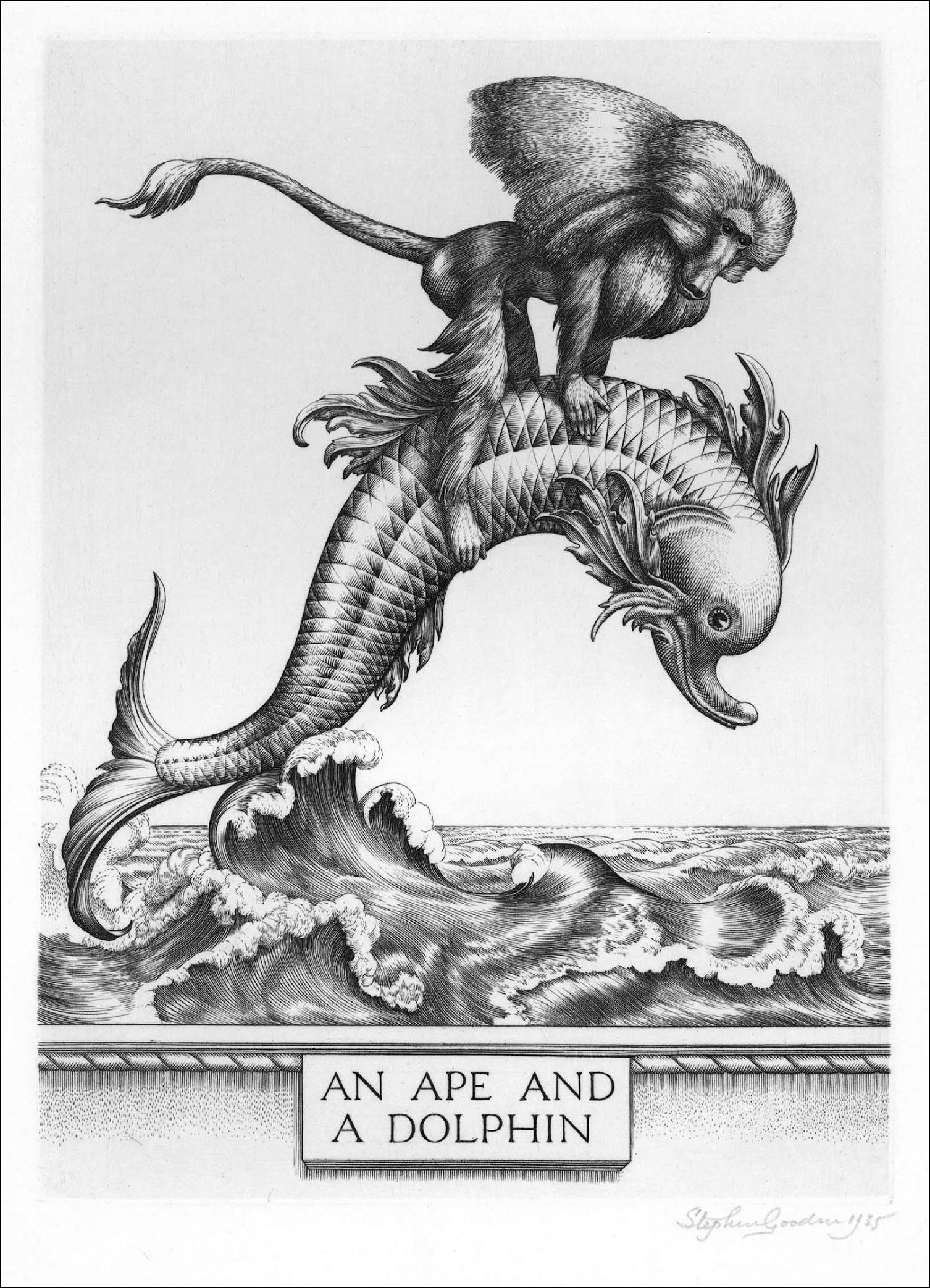

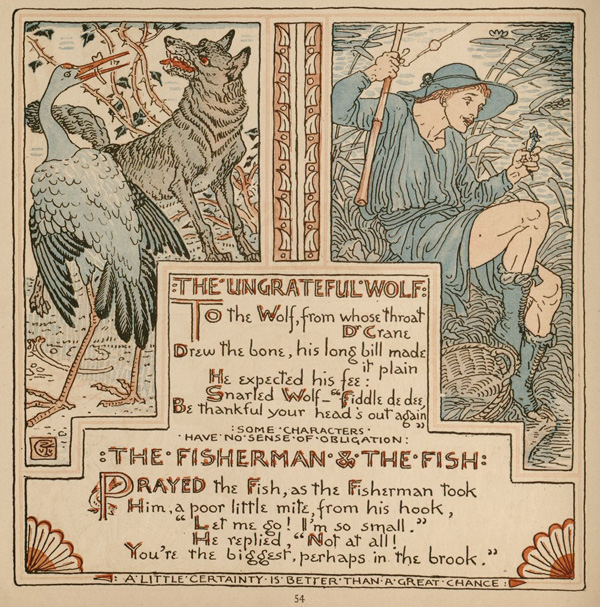

The art prompted by these old moral tales is more than illustration. Like depictions of classical mythology, the images use an expressive language of visible form that incarnates something of the age that produced them. Something, too, of the inner life of the artist who made them.

Below, a sampler of favorite Aesopian savories: