Francis is the first pope to tour the Venice Biennale. May he be the last.

A good deal of sugar has been spun from the unexamined conceit that art—Art—is a moral pill to treat social problems. A trademark of upper-middle and upper-upper class groupthink, it was in high relief on Sunday, April 28. That day Pope Francis helicoptered to Venice for a tour of the exhibition “With My Eyes” at the Holy See Pavilion.

The word pavilion here is a moveable concept that applies to a temporary installation housed this year in the women’s prison on Venice’s Giudecca Island. Reflecting the Vatican’s internal secularization, the installation is devoid of anything that might be called a Christian aesthetic. Instead, it bows to the ever-expanding category of human rights and Francis’ touted concern for life on the periphery—as he defines it.

Begin with Maurizio Cattelan’s huge mural commissioned for the facade of the prison. It announces the caliber of mind of the Vatican’s chosen curators. Cattelan is a celebrated art world bad boy—a provocateur unafraid to soil the decencies. [He has stoked controversy over, among other things, a solid gold toilet, a $120K banana taped to a wall, and a life-sized wax effigy of Pope John Paul II felled by a meteorite.]

This year Cattelan returns to the Biennale with a three-story high photo-realist painting of the soles of his own dirty feet. The image presumes to evoke Jesus washing the feet of His disciples on Holy Thursday. Inevitably, the allusion negates the meaning of the Gospel story more than affirms it.

As John 13:12-15 records the moment, Jesus kneels at the feet of the Twelve in a private room, out of public view. He did not take a towel to the feet of random pedestrians on the Jerusalem pilgrim road. Jesus washed only the feet of his own intimate circle—fellow Jews destined to die one day for their trust in Him. He commanded them to care for one another: “If I, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you ought to wash one another’s feet.”

One another is the key phrase. Jesus’ tender instruction was directed to His own (John 10: “I know mine; and mine know Me.”) in order to sustain a body of believers in spiritual communion with each other. Since Pope Paul VI’s overhaul of the liturgy, a dissolvent sentimentality began to melt traditional understanding. Ceremonial reenactment of what Jesus conveyed to a cherished fellowship flattened into a sentimental gesture. In most parishes now, the Holy Thursday foot washing is largely a maudlin symbol of social justice concerns and ecumenical manners. [The feet should be racially mixed; there must be women; a Muslim makes a good touch.]

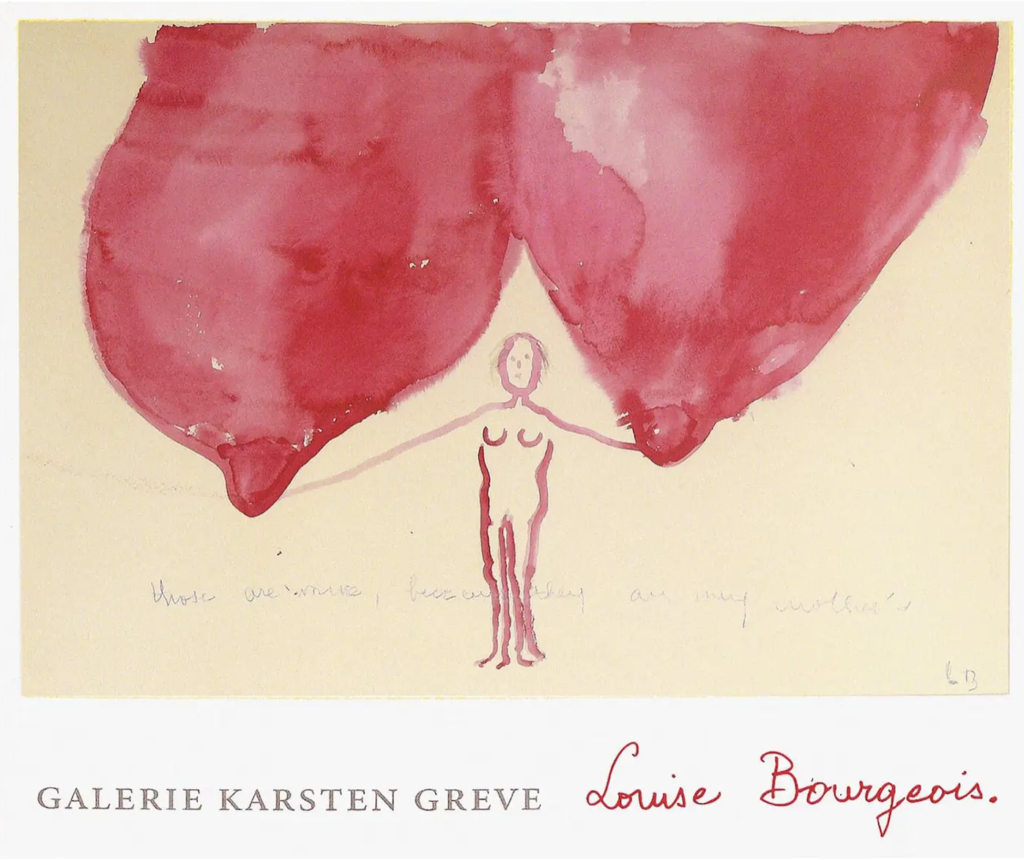

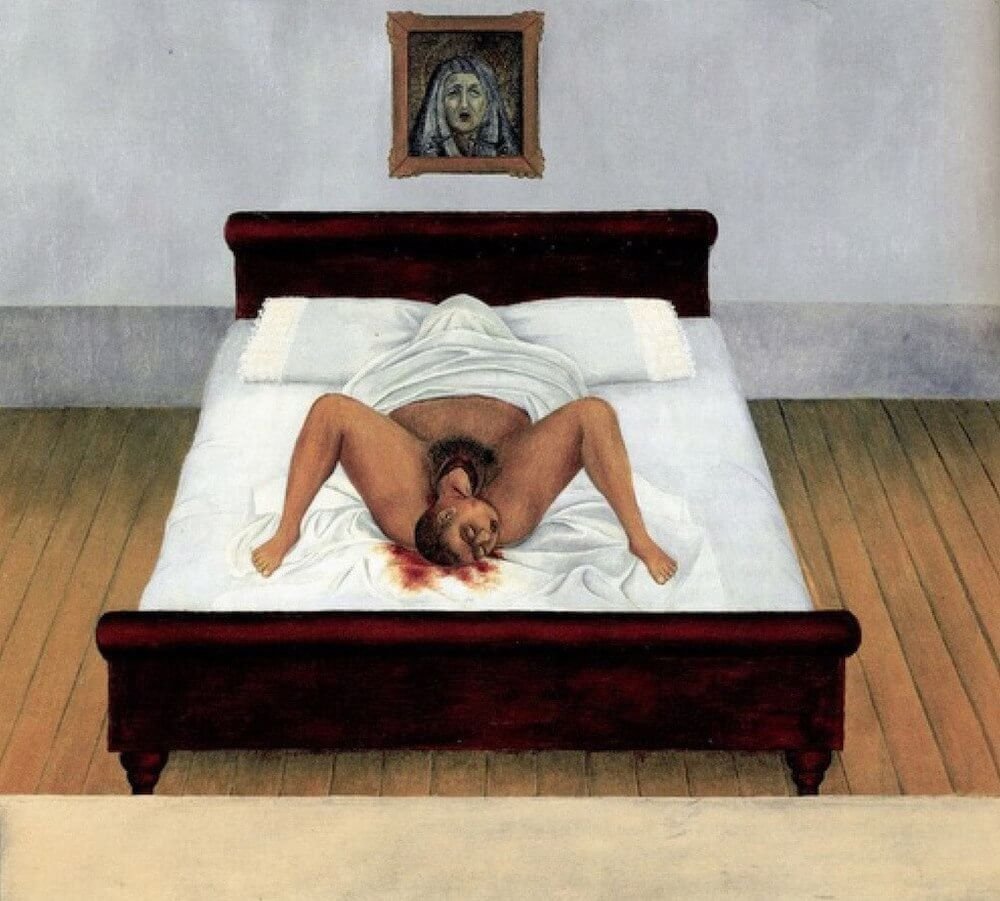

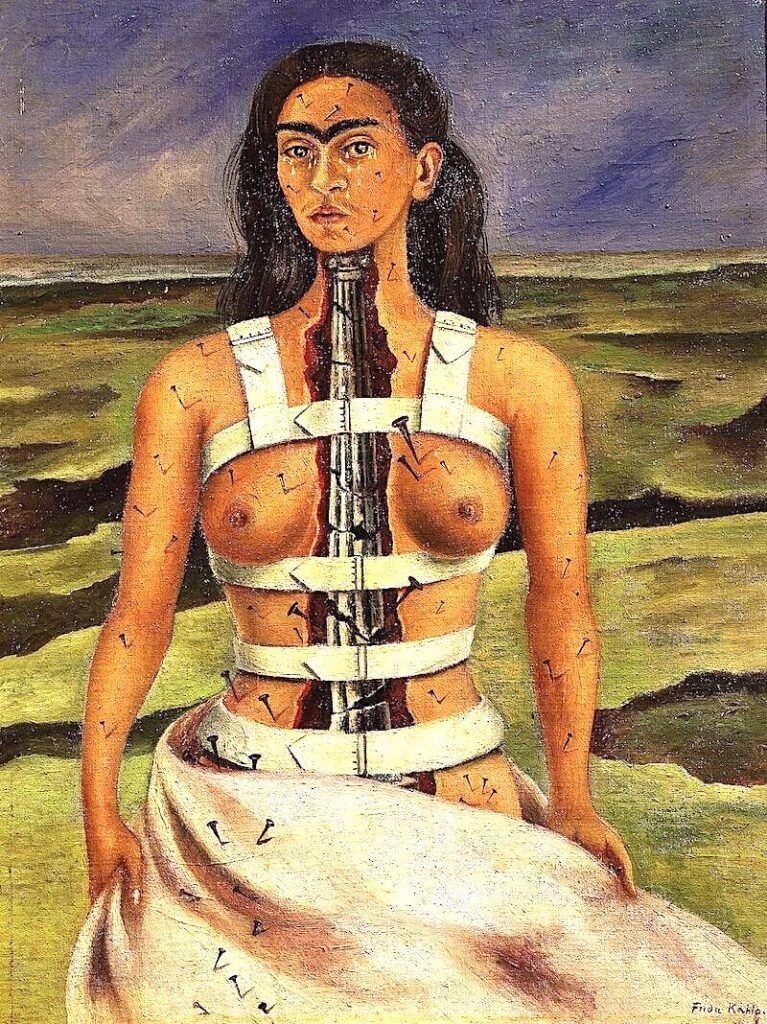

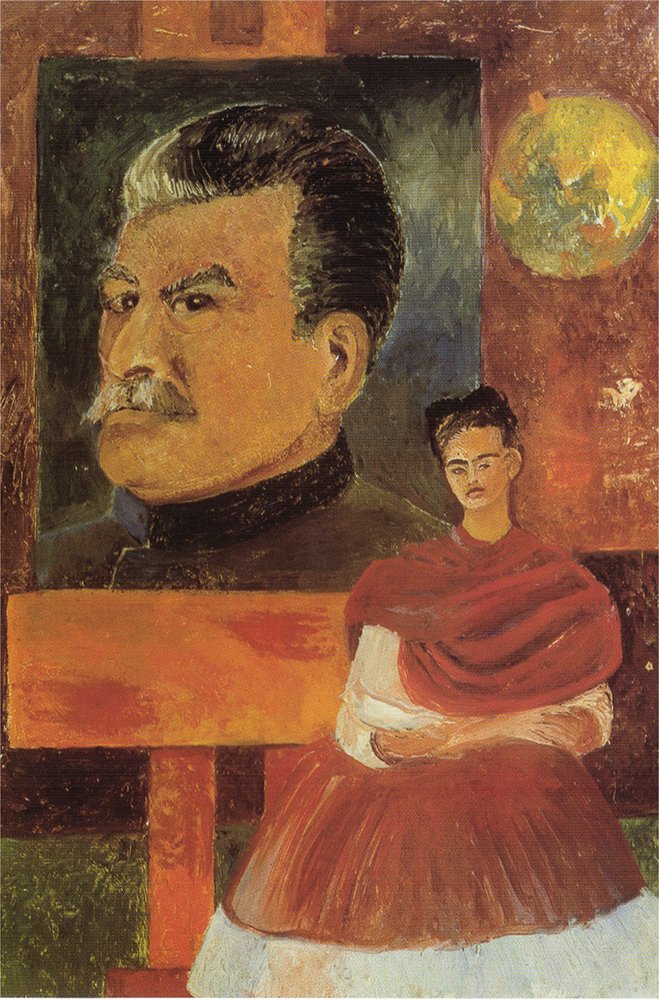

Artnet quoted from Francis’ address to the inmates. He asserted art’s power to address social ills. Since many of the prisoners participated in the event (painting, writing poems, acting in videos), he crooned “the world needs artists.” Flattering a female audience, he praised women artists like Frida Kahlo and Louise Bourgeois. “I hope with all my heart that contemporary art can open our eyes, helping us to value adequately the contribution of women, as co-protagonists of the human adventure.”

Whoever whispered those names to the papal ear had their eyes on trendy media biases, not on visual art. There is no mention of any work by Kahlo or Bourgeois appearing the exhibition. Their names were invoked to suggest papal sophistication and empathy with feminist iconography.

But since the pope brought them up, let us have a look.

Both women have been mythologized out of proportion to their production. Posthumously installed in LBGTQ legend, both obsessed over sexuality, the human body, and body parts. Each in her way moved contemporary art’s needle closer to narcissistic exhibitionism and the promotional value of a finger in the viewer’s eye.

Kahlo was a minor talent inflated into a major one by identity politics (including Mexican nationalism) and artworld access provided by marriage to Diego Rivera, the great Mexican muralist. She is the darling of women who once cried over Sylvia Plath and grew up to carry @MeToo tote bags. Her painting was a relentless obsession with herself as sign and symbol of eternal female suffering—Frida, Woman of Sorrows. Her prominence owes as much to the maudlin chauvinism of her work as on the names she slept with.

Bisexual, she kept up multiple affairs with both men and women (sculptor Isamu Noguchi; Georgia O’Keefe; jazz singer Josephine Baker; actress Gloria del Rio, et alia) before, during, and after her marriage to Rivera. Her most celebrated affair was with Trotsky to whom she dedicated a 1937 self-portrait: “To Leon Trotsky, with love . . . .” Both she and Rivera were committed Stalinists. “I want my painting to be useful to the Communist movement . . . .” she wrote.

Louise Bourgeois came to prominence as the fag hag of the alliance between gays and feminists against standards of artistic competence. Aspirations to the creation of beauty are nothing more than patriarchal colonizations of the creative spirit. Bourgeois’ celebrity owes entirely to her contribution to an anti-art reign of terror against Western canons of achievement. Or, as the feminist art movement saw it, against the fallacy of patriarchal genius. Bourgeois’ work liquidates centuries of Western achievement in figurative art.

Perhaps Francis had no idea of the cult of ugliness that Bourgeois represents. And possibly he was equally unacquainted with her activism on behalf of gay marriage and LBGTQ “rights.” But it is impossible to believe that the Vatican artminds in the Dicastery for Culture and Education, advisors on the project, were in the dark.

As Artnet reports, Francis told the roughly 80 women inmates “that they hold a special place in his heart.” The remark conveys an illusion of pastoral concern at variance with reality. He knows not a single one of them. He knows nothing of the reasons for their detention, not the gravity of individual offenses nor the length of anyone’s sentence. Pilfering or child abuse? Prostitution or assault? No matter. To the fashionable contemporary mind, all women are victims of some System or other.

The women were enjoined to rebuild their lives. Yet the distinctive role of religious faith in spiritual rebirth, which the Church exists to declare, went unmentioned. Absent any expression of the transcendent source of moral seriousness, the Holy See Pavilion showcases the good intentions of secular humanism. By default, it magnifies art—Art—as modernity’s redeemer. This is the mechanical position of a culture that venerates Art in what Jacques Barzun referred to as “the vacuum of belief.” Without intending to, the Holy See accommodates the dominant enthusiasms of a secular culture’s substitute Church.

Leaving the prison, the pope moved on to an open-air Mass in St. Mark’s Square. There he warned attendees of the future effect on Venice of climate change and over-tourism.