Harrison Butker’s commencement address at Benedictine College was a mixed pleasure. There was much in it to cheer. Nonetheless, his spotlight on Josemariá Escrivá de Balaguer, (1902-1975), founder of Opus Dei, raised a red flag. How familiar is Butker with the richness of Catholic tradition beyond the contours of a quasi-sectarian, ultra-orthodox movement hinged on a personality cult?

More on that later. But first, the pleasure.

Part homily, part pep talk, the address challenged young Catholics to recognize the moral bankruptcy of the culture they will inhabit as adults. It took aim at the rancid spectacle of Biden making the Sign of the Cross at a pro-abortion event. It was was blunt about the dereliction of bishops who behave like chancery hirelings rather than shepherds. Butker emphasized the primacy of family life, and noted the scourge of fatherlessness. His final thrust at “the cultural emasculation of men”—a feminized masculinity, all empathy and warm baths—could have earned a fist pump from Ignatius Loyola.

Reaction to the address was delicious. While talking heads, scribblers, and the pussy-hat crowd clutched their pearls, The Babylon Bee reveled in the comedy of media-driven hypocrisy. Alert to NFL players accused of domestic violence, The Bee ran with the headline: “ ‘Harrison Butker Does Not Reflect Our Values,’ Says League of Women Beaters.”

NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell in a statement defending the league of depraved convicted criminals who make millions playing a game while abusing women in their free time. “We sincerely apologize for Butker’s inexcusable support for family values. We want to reiterate our commitment to continue filling the roster of all our franchises with violent criminals who would probably be in prison if they weren’t working for us.”

Kansas City Chief’s star kicker knew his audience. He gave a talk that conservative and tradition-minded listeners wanted to hear. His celebrity insured it would be broadcast—clickbait for popularizers of cultural decay no less than for fellow Catholics.

But much slipped under the radar.

What prompted Butker to draw deferential attention to Escrivá—and, by association, to a controversial sect with a ticklish relation to the Church that engendered it? To serious critics, Escrivá was an uneasy candidate for sainthood: a vain man with an appetite for opulence and position. Camino (The Way), an anthology of his 999 maxims, offers no profundity, no evidence of heightened spiritual insight. Escrivá’s rather banal, derivative writing undersells the aura of distinction he cultivated around himself. The rush to his 1992 beatification and speedy canonization ten years later remains an unedifying case study in pressure group tactics and ecclesial politics.

So why Escrivá? The Church has accrued a rich treasury of meditation on the ministerial priesthood. Reflection—that lovely word—runs deeper than the boilerplate Butker quoted: “Priests are ordained to serve and should not yield to temptation to imitate lay people but to be priests through and through.”

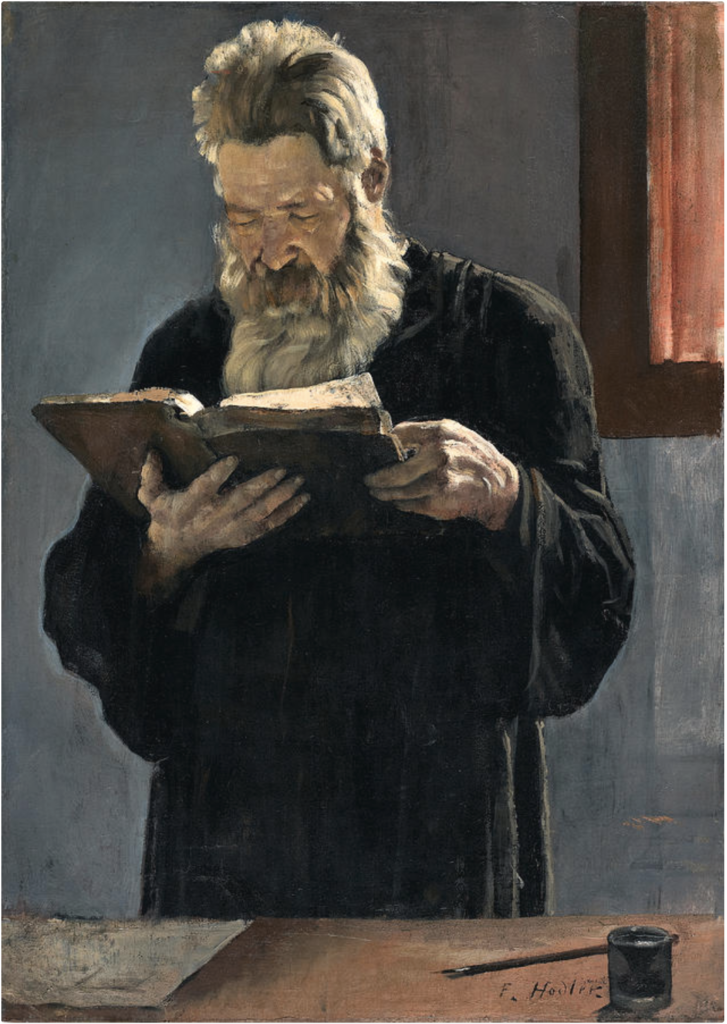

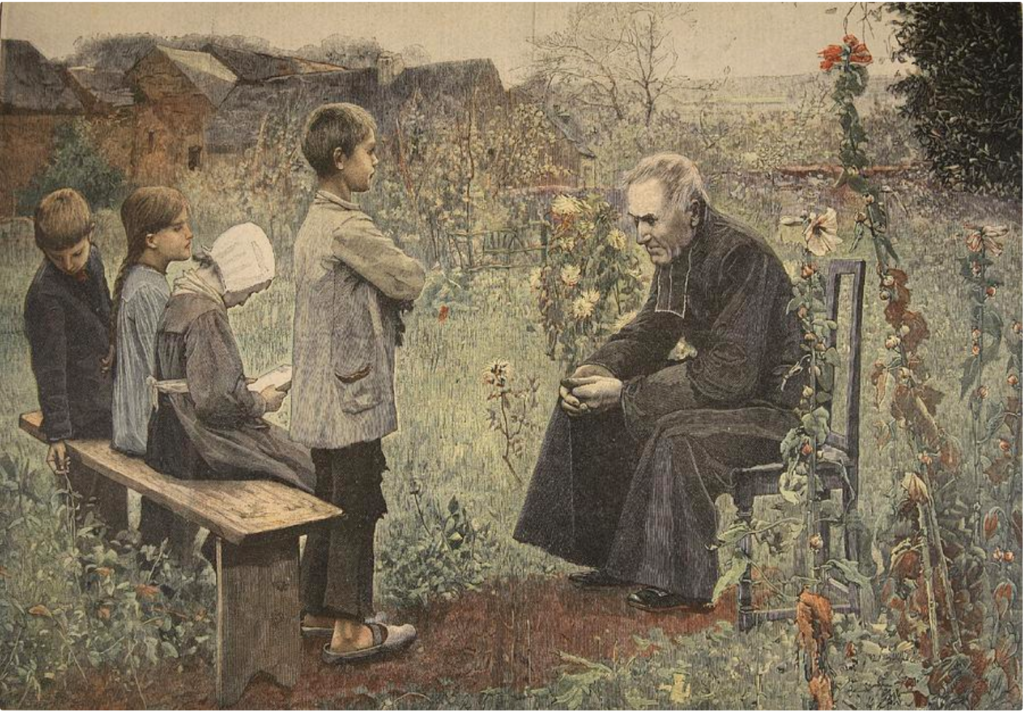

St. John Vianney (d. 1859), famed Curé of Ars and patron saint of parish priests, is a worthier source for the same subject: “Do not try to please everybody. Try to please God, the angels, and the saints. They are your public.” St. Philip Neri (d. 1595), advised similarly: “Let him [the priest] aim for joy rather than respectability.”

Butker bypassed two encyclicals on the priesthood, and ignored multiple passages in the Catechism on the nature and role of ordained ministry. Was he aware of them? He might have quoted easily from Pius XI’s Ad Catholic Sacerdotii (1935): “. . . . his office is not for human things, and things that pass away, however lofty and valuable these may seem; but for things divine and enduring.” He could have cited Paul VI’s Presbyterium ordinis (1965). It is generous toward the humanity of men who live out their call to a life of perfection within the constraints of social life:

Priests, who are taken from among men and ordained for men in the things that belong to God in order to offer gifts and sacrifices for sins, nevertheless live on earth with other men as brothers. . . . But they cannot be of service to men if they remain strangers to the life and conditions of men.

Such generosity went missing from the talk. Butker applied the lash to priests who exhibit common human foibles, e.g., photographing themselves with their dogs. He carped at priests he deemed “too familiar” with parishioners. By this he meant nothing more culpable than ordinary affability. Yet, the Catechism offers a lesson in charity on such matters: “The presence of Christ in the minister is not to be understood as if the latter were preserved from all human weaknesses. . . .” (#1550)

In short, a priest’s fond photos of himself and his dog are nothing against his sanctity. (Pope Benedict VI was no less holy, no less God-centered, because of his exaggerated fondness for cats, and photos of them.)

Butker disdained priests whose happiness—in his view—owes too much to the “adulation they receive from parishioners.” How, precisely, does a layman calibrate degrees of priestly happiness? More to the point, Butker’s derision is out of sync with Escrivá’s own cultivation of hero worship. In addition to pretentious changes to the family name, petition for the aristocratic title Marques of Peralta and other honors, there was Escrivá’s promotion of himself as “The Father”—as he preferred to be known by his spiritual children:

Who are you to pass judgement on the decisions of a superior? Don’t you see that he is better fitted to judge than you? He has more experience; he has more capable, impartial and trustworthy advisors; and above all, he has more grace.” (Camino)

Let ourselves be led like little children . . . violently rejecting the tendency to manage ourselves. (Cronica, a men’s journal circulated within Opus Dei.)

“The Father” knows best.

Again, why Escrivá? The acknowledgment cast a crooked light on Butker’s repeated exhortation to graduates to “stay in one’s lane.” In other words, laymen—women in particular—must know their place. Theirs is not to reason why, not question their hierarchical superiors. (“. . . unless you are a theology major.”) Escrivá’s Maxim #61 reminds followers that “laymen can only be disciples.”

Notwithstanding the authoritarian tenor of Escrivá’s vision for rank and file Catholics, The Father urged his male followers “Be firm! Be strong! Be a man!” And “Tender, soft. flabby . . . that’s not the way I want you.” Doubtless, such admonition resonated differently in Spain in the 1930s—the era of General Franco, el caudillo—than it does today. Nevertheless, it dovetails with Opus Dei’s strict distinction between the roles of men and women, a distinction Butker made a bit too much of.

Marriage and parenthood are vocations embraced jointly by men and woman. Men, too, are called to the contingent demands of homemaking. It takes mutual, sustained commitment between husband and wife to create and maintain a family—a home. Yet Butker assigned homemaker to women alone. In that narrow context, the word is proxy for housewife, a noun that, in common usage, defines a woman’s status solely in relation to a man. [Which is why a single mother supported at home by state assistance is called neither housewife nor homemaker. And why a woman does not have to be one of the the feminist Furies to wince at the comment.]

• • • • •

Escrivá’s Maxim #946: “Women needn’t be scholars; it’s enough for them to be prudent.”

• • • • •

Most women already know where their hearts lie: in their marriages, and their children’s well-being. But too few have an option to leave the work force and stay home. It was Butker’s prowess on the playing field—his career—that provided him the public platform to deplore the signs of our times and proselytize on behalf of the traditional Latin Mass.

Earning a near-five million dollars (in salary and product endorsements) this year, he can well support a stay-at-home wife. How many men can say the same? Most of them have jobs, a different category of work than what we call careers.

Butker could not have given the same speech to graduates of the local community college. In 2021, medium household income in Atchison, Kansas, was $48,880. How many working Catholics, in Atchison or elsewhere, can afford Benedictine even in a stable economy let alone one headed for recession? A private college, it charges $35,350 for tuition plus a $8,350 residence fee sans board. Meal plans range from $3,000 to $5,850. (Freshman are required to take the priciest plan.) Unless students come from relative affluence, both sexes graduate with a burden of debt.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, among married-couple families with children under 18, in 67.0 percent of these families both parents were employed in 2023. Following economic news, we read that families are increasingly tapping into their 401(k)s to cover the cost of living.

Butker congratulated himself for having delivered “hard truths.” In reality, he left out some quite significant ones. Our kicker is an enthusiast, chosen as a commencement speaker for his celebrity, not breadth of learning. But enthusiasm needs to be tempered—informed; regardful of nuance—before it is put on show as a media event by publicity-conscious college administrators.