Studio Matters began as a companion to my columns for the culture desk of The New York Sun in its brief reincarnation as a print edition. I often miss my weblog’s original mandate.

At the time, The Sun ran the best arts coverage in New York City. A small troupe of us covered visual arts for the culture desk under the heading “Gallery Going.”

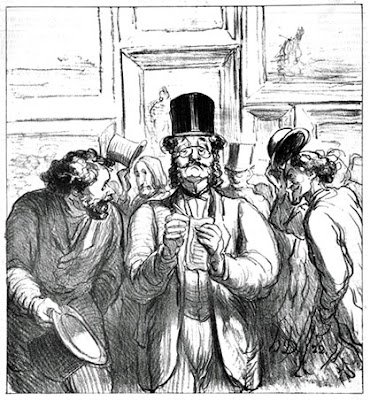

Journalistic art criticism has been with us since the Mercure de France published the first criticism of a Paris Salon in 1738. By now, criticism has become an indispensable tool of the art market. (Before the modern age, artists did not work on spec. The patron who commissioned a work of art became its buyer.) Contemporary arts commentary is tethered inescapably to the promotional needs of both artists themselves and impresarios of the trade—dealers, institutions, and their collector-donors.

Constraints notwithstanding, “Gallery Going” did its best to provide readers a context for judging the aesthetic and cultural worth of the artwork in the dock. Values external to the work of art itself—i.e., market value; the status of a gallery; advertising revenue—were askance of the column’s intended function. And the culture desk aimed for intelligible language free of lyrical effusions and philosophical pretensions.

In other words, the column aimed at criticism—something sturdier than artwriting. An ear for cant and an eye for gall and wormwood went with the job.

That ambition distinguished The Sun from the art-and-entertainment sensibility of more established publications. A curator at the Metropolitan Museum put it succinctly to fellow critic Lance Esplund: “We buy The New York Times. But we read The Sun.”

Enter First Things. The editor was scouting for refined arts coverage with a Christian perspective— wherever, and however, it might apply. A woman writer would be just the thing. So Studio Matters was invited onto First Thing’s internet platform as an independent in-house weblet. It served as a cultivated reader’s postprandial: a good-quality digestif after the high cuisine of the journal’s main meal.

There was no pay for the labor. A free hand with subject matter and opinion, was all. With art—Art—teetering on the verge of a transcendental, reflection on the subject need suffer no relation to the sullying effects of cash. Such was an editorial assumption that, in its way, confirmed the view of my mother-in-law: writing about art was not real work. (“When will Maureen get a job?”)

Nevertheless, I took the offer.

The move onto First Things’ server brought with it a different audience from readers of “Gallery Going.” Little by inexorable little, audience druthers shifted content from art talk to Church talk and—necessarily—papal doings.

Studio Matters was de-platformed nearly eight years ago. Yet I still engage that shift in topics and emphasis. It concerns me even more now than ever. Nonetheless, what visual art is and has become, how it is felt, thought about, marketed, and imitated is a serious matter. All the more serious for art-at-large having swollen into a surrogate for religious experience and—among the Left especially—a moralizing nag. Besides, art history told straight, without the filter of a canned survey, is engrossing and revealing.

Lively-minded people who take delight in looking—the simple act of it—are different from the priesthood of ordained Art appreciators. The latter are a sanctioned caste who promote one or another theology of artistic sensibilities. A prominent evangelist of the modern artist as an alter deus, John Dillenberger wrote:

They [Jackson Pollock and Barnett Newman] strive to be primordial. Yet they do not portray how reality is perceived; that is, they are neither this worldly nor other worldly. Their transcendence is in their very presence. They are tragic, grand, sublime—that is, ourselves when freed of many of the overlays of history. They are, analogously, meant to be like God’s pure creation.

Dillenberger followed the lead of fellow theologian Paul Tillich. Dubbed “the unbelieving theologian” by his grandson, Tillich spent much time in the Hamptons socializing with a self-conscious avant garde who believed their own mythologizing. A certain kind of social conditioning was at work in those many cocktail parties on Long Island’s wealthy South Fork. Among art-conscious aspirants to social station and intellectual prestige, aesthetic sensation was—and remains—what Edward Norman identified as “the acceptable face of materialism presented as if it was radiated by higher values.”

In sum, all this is a preface to saying that Studio Matters will make good on its name a bit more frequently. I trust you will not object.

Related Notes:

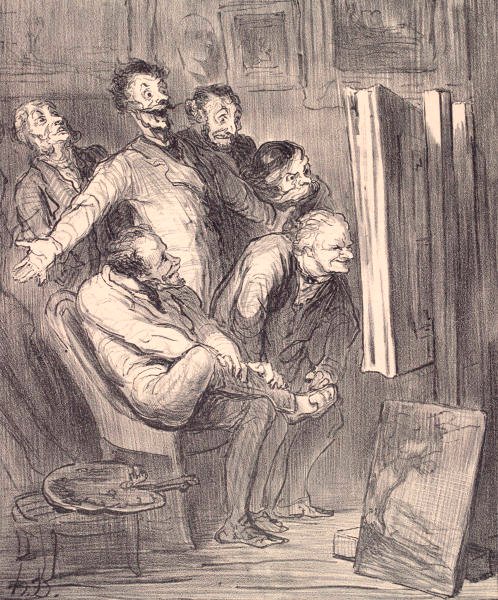

Toward the late-1800s, Edgar Degas complained that there were—even then!—too many artists. More recently a Catholic editor, himself a religious studies maven, admitted that the same was true of theologians. In its way, the admission acknowledged that authentic culture, including religious culture, is a homelier pursuit than today’s relentless output from artists and theology departments would have us think.

Teeming quantities of art works, off the conveyor at an astonishing speed, signal what Louis Bouyer interpreted as signs of the twilight of culture:

The clearest symptom of this deep cultural degeneration is to be found in an abundant artist activity, frantically but vainly seeking a distinctive creativity which is reaching exhaustion in a torrentially productive outpouring, whose ever-increasing rate of production cannot hide a fundamental inner sterility. Here too, the machine has invaded, so to speak, the spirit’s corporeity, which in this . . . flow is now losing what is left of its soul.

Fr. Bouyer fired off that volley some forty years ago. Today we might say the same about the contemporary flood of theological products: e.g., a theology of baseball; proposals for a new theology of the body; a theology of style; theologies of creativity and imagination; a theology of home, et alia. Add modernity’s accelerated pressure on the machinery of branded papal products: exhortations, proclamations, taped interviews, broadcast speeches, and solemn encyclicals anxious to keep pace with climate change and elite opinion.

Laudato Si’ is Francis’ theology of integral ecology. As Fr. Bouyer might ask: Are these projections of ourselves—of our politics and lifestyles—simulating a relationship with and a dependence on God?

• • • • •

Pope Honorius III (1216-1227) was among the most eminent administrators in Church history. In the eleven years of a vigorous, productive, and consequential pontificate, Honorius is best known for a single legal document: Solet Annuere, a bull establishing the rules for the Friars Minor of St. Francis.

• • • • •

The spiritual life is profoundly simpler—consequently more difficult—than a flood of theologized designs. The ancient psalmist grasped the heart of things: “Be still, and know that I Am God.” That, and the luminous words of Gerard Manley Hopkins: “To the Father / through the features of men’s faces,” are bedrock.