COMING IN OVER THE TRANSOM LAST NIGHT, and again this morning, were various expressions of pious regret at the death, yesterday, of Louise Bourgeois. “Yet another great loss in the arts” intoned one e-mail. “She will be missed,” said another.

Not as an artist. And not by me.

Louise Bourgeois has passed into mystery. To that, we rightly bow our heads. “It is meet and just to pray for the dead” was the motto posted in my grade school classroom during November, the month of the Poor Souls. I was touched by the words then and still am. But beyond that, I am not among the mourners for Bourgeois. I did not know her and dare not add to her obituary. The New York Times has a brief summary here. London’s Guardian has an extensive one here. And The Huffington Post comments here.

What matters to me—and remains fair game for discussion—is her art. The debased character of so much of the work, the falsity of its promotion, and its unfortunate influence on younger artists, especially women, is nothing to celebrate.

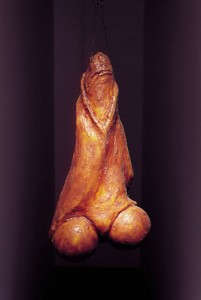

The aggressive vulgarity of her later sculpture and drawing, with its patina of confessional pathos, suited the times and the feminist art movement. Her notoriety owes itself to the success of the movement’s dismissal of hard-won mastery as “mere skill.” It snubbed the canon of Western art as evidence of male dominion over the criteria for legitimacy and achievement and touted such unsmiling things as Bourgeois’ latex phallus, Fillette:

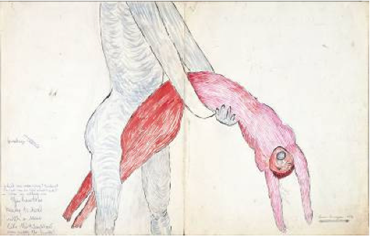

Bourgeois’ imagery was in sync with the feminist art movement’s luxurious cant and mélange of no-styles that took root in the kampfzeit rhetoric of the Sixties. No more nice girls. No more counterrevolutionary submission to male definitions of culture. The phenomenon of Bourgeois as a feminist icon depended on self-serving assent to Linda Nochlin’s toxic notion that no appropriate “language of form” existed for women. So, it was time to get bawdy, to stop catering to the depraved tastes of the bourgeoisie and throw out the spiritual weapons of a dying class. Women’s art was Another Cuntree in which patriarchal standards need not be enforced.

Drawing suffered more than anything:

Then there was Maman, that trademark spider, with all the emotional depth and resonance of a Halloween prop. A fun sculpture for a school yard, it contributed to Bourgeois’ inclusion in the U.S. Women’s Hall of Fame, along side Emma Lazarus:

Relentless depictions of body parts—breasts, male and female genitalia—were aimed at the coercive power of norms, whether aesthetic or sexual. Mutually reinforcing, feminist art theory and a camp aesthetic egged each other on in sorties against transmitted understanding of artistic achievement. Together, they gave us what academia might call the poetics of transgression. Both were—still are—vulgar initiatives that traded on the susceptibilities of their audience.

The single interesting point in Bourgeois’ bio is that she was married to art historian Robert Goldwater. He participated in the famous, informal gathering of art scholars organized by Meyer Schapiro around 1935 that included Lewis Mumford, Alfred Barr, Erwin Panofsky, James Johnson Sweeny, and art dealer Jerome Klein. Goldwater, a scholar of African art and the first director of the Museum of Primitive art, wrote on the relation between primitive and modern art. His work cut a path for that of his wife. It provided her incapacity for refinement (or rejection of it) cover under the pretext of something primordial. It was a romantic canard that fit nicely with Womanart’s sententious and stagey narcissism.

It is meet and just to pray for the dead. But that has no bearing on art.

© 2010 Maureen Mullarkey