Mortality was much on the mind of St. Augustine. In The City of God, he exhibits skepticism that a world thoroughly free of death-dealing plague could ever be possible. The tenor of this old quatrain has an Augustinian ring:

Doctor, Doctor,

will I die?

Yes, my child,

and so shall I.

Like the original wording of many eighteenth century nursery rhymes, the lines irritate modern ears. Twentieth century sensibilities revised it to suit a well-fed, housed, and vaccinated generation poised to dismiss dispiriting reminders of mortality. Our new, unobjectionable version sidesteps the enigma of death:

Doctor, Doctor,

will I die?

Count to five,

and stay alive.

Mood and purpose disappear along with the old rhyme scheme. No matter the tenderness of his delivery, the first doctor’s realism offends. More congenial to contemporary habits of mind is a couplet that imitates a warm-up exercise barked by a fitness coach. A simple memento mori in chant is drained of its significance in order to shield listeners from the truth that death is universal and inevitable.

By now we are at least two, if not three, generations removed from memory of the opening line of the venerable Gregorian antiphon: Media vita in morte sumus (“In the midst of life, we are in death”). Why trouble ourselves with the melancholy of our less knowledgeable forebears? Modern medicine and know-how permit us to keep postponing death longer and longer for more and more people. Nowadays, that ancient prompt, “Remember that you must die,” smacks of a nuisance call.

Or it did until the latest Chinese virus arrived. Now we all count to five, reciting incantations (“Flatten the curve.” “Stay safe.”) to keep the Pale Rider at bay. Lulled by the historic success of efforts to improve—and lengthen—our lives, we forget our evanescence. We are shocked into panic and societal free-fall by an unwelcome signal that we are ever in the mills of death. Its brute presence has been with us all along. We dread the reminder.

• • • • •

COVID-19 warns us that illness—and with it, death—is inherent to our creatureliness. If ever there were a time to reflect on our constituted nature, its meaning and destiny, this is it. Thomas Aquinas was blunt: “Of all human evils, death is the worst.” What providential purposes are served by this “most extreme of all human suffering”? Francis’ Urbi et Orbi homily locates the why of this pandemic in punishment for sin. Not personal sins, mind you; not the ones we bring to the confessional box. Rather, Francis insinuates transgressions of an ideological kind, ones that grate on the consciences of self-chosen world-improvers:

Greedy for profit, we let ourselves get caught up in things, and lured away by haste. We did not stop at your reproach to us, we were not shaken awake by wars or injustice across the world, nor did we listen to the cry of the poor or of our ailing planet. We carried on regardless, thinking we would stay healthy in a world that was sick.

The word “sick” here does not refer to physical illness. It invokes—in code—those flawed, bourgeois Western structures for which Francis’ has a panacea-in-waiting: the “Economy of Francis.“ Initially scheduled to debut this March, this conference of activists, convened by the pope, will unfurl in November:

The title of the event clearly refers to the saint of Assisi, an example par excellence of care for the least of the earth and for an integral ecology, but it also refers to Pope Francis. Ever since he wrote Evangelii Gaudium and then Laudato Sí, he has denounced the pathological state of so much of the world ‘s economy extending an invitation to put in place a new economic model.

• • • • •

Francis cracked his own code this week by dropping the suggestion that Wuhan flu is nature’s retaliation for man’s resistance to the means necessary to combat climate change. The unspecified culprit is Western man whose rate of production and consumption galls Mother Earth. (John Nolte called it “nothing short of a blood libel.”)

Burrowed within Francis’ use of Gospel passages is obsession with the utopian politics of planetary management. It carries a highly selective secular ethos. Jorge Bergoglio would bite off his own tongue before he blamed homosexuality for the spread of HIV/AIDS. But he pins the tail on Western prosperity for the spread of a virus unleashed on the world by Chinese Communist Party malfeasance.

• • • • •

Francis’ utterances tend toward an incoherent blend of popular tropes and New Testament references yoked together with ragged Leftist ties. His Urbi et Orbi address restates, in part, the saccharine lyrics of “We Are The World,” a 1985 Grammy Award winner:

There comes a time

When we heed a certain call

When the world must come together as one . . .We’re all a part of God’s great big family

And the truth, you know, love is all we need.

The papal version puts it this way:

[Embracing His cross] means finding the courage to create spaces where everyone can recognize that they are called, and to allow new forms of hospitality, fraternity and solidarity.

Create spaces. Blush, oh my soul! That this reductive banality passes as a guide to meditation on the meaning of the Cross is embarrassing. Those last three words evoke nothing of Christian understanding of the dreadful love beheld on the Cross. Instead, they stand proxy for pet issues of the globalist Left, open borders chief among them.

Hospitalité, fraternité, solidarité. Heady slogans, they sound somewhat familiar. History has been through this door before. Only the veneer of religious reference veils a view of what desolation stretches beyond that bloody old gate.

• • • • •

This year’s Urbi et Orbi address, a one-hour TV special, left me unmoved. It was an appalling production

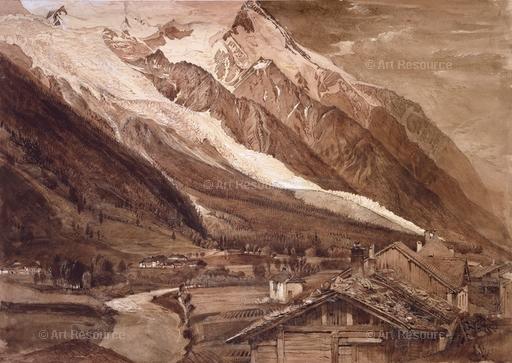

On March 27, Pope Francis stood alone in a deserted St. Peter’s Square—lit for broadcast—to pray that God will end the pandemic. He held a monstrance aloft for the cameras. The gesture mimicked processions led by priests or bishops into Alpine fields to stay advancing glaciers during the Little Ice Age. (A relentless, slow-descending incursion of ice and compacted snow, glaciers caused famine, destitution, and flooding in Alpine countries during those centuries, c.1300s to mid-1850s.)

It was brilliant showmanship.

Whatever else it might have been besides stagecraft, I hesitate to say. But for Catholics, the Blessed Sacrament housed in the monstrance is an object of adoration. In a setting dramatically empty of worshippers, the raised monstrance appeared less an act of benediction than something to which magical power attached—the Eucharist as a charm, a Catholic totem. Here was Francis performing an act of shamanic healing.

It would be careless to ignore the absence of papal theatrics against any other of nature’s catastrophes to which the world is subject. To name only three miseries stalking the globe, consider coronary artery/heart disease. The world’s preeminent slayer, it annihilates 17.9 million people a year, or 31% of all deaths world wide. Cancer is the runner-up in global extermination stakes. Diabetes extracts its due. Yet no ostentatious piety marks their death toll. While these killers are not passed from person to person—as is AIDS—their resultant pain and anguish are universally the same. Besides, as we shelter in place, odds are high that most of us are incubating one or another killer on WHO’s roster.

• • • • •

In 2018 an estimated 228 million cases of malaria occurred world wide, some 93% in Africa. No one took a monstrance “to the margins” of Nigeria, Uganda, or the Congo to halt the spread of malaria. Deutsche Welle cited the top ten most dangerous viruses in the world, all centered in the Third World and/or the tropics. Africa’s Marburg virus, like Ebola and its viral relatives, has a mortality rate of 90%. Dengue fever is a continual threat that affects between 50 and 100 million persons each year. (WHO expands the number to 100-400 million.)

No papal medicine show attends these diseases. They are useless as ammunition against Western economies.

• • • • •

The pope would have us spend more time contemplating the natural world. So, let us begin by contemplating today’s celebrity pathogen.

SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is a submicroscopic unit of the same creation lauded by Laudato Sí. Though the encyclical ignores them, viruses contributed to the rise of cellular life, over a billion years ago. Before there was a snake in Eden, there were viruses. Enigmatic factors in the very stuff of existence, they play their own role in the grandeur of creation.

God works within time and at His own pace. Built into nature are the very agents that ensure mortality, ours that and of every living creature. The Creator “of all things visible and invisible” ordained them to behave—in concert with vast cosmogonic contingencies—precisely as they do. Every bacterium and virus, every sly assault on our bodies is part of His handiwork. Genesis tells us: “And God saw every thing that he had made, and, behold, it was very good.”

Participants in the dignity of matter, pathogens and their transmitters—fleas, ticks, mosquitoes, worms—share the clay of which we are made. This selfsame clay arose within a dynamic universe, a nexus of mind-surpassing forces that shatter stars, alter climates, arouse tornadoes. The freedom of these works precedes man’s presence among them.

Behold, it was very good. Man is born into the maelstrom of this goodness—a harrowing bounty—and granted dominion over it. His vocation calls him to gather his God-given wits to tame this fearsome gift. Western man has done just that, wonderfully so. Seared by the brevity of his days, he lays hold of instruments to identify vectors of disease; to foil pandemics, to conquer each pestilence as it comes. And come they will.

Pestilence is as natural as rain.

It is mortality alone that decisively defeats man’s endowed intelligence. If only our politically driven pope had a taste for reflection on the substance of our mortality. It is “the blight man was born for,” as a Jesuit poet wrote. The sorrow of living has a home in its tyranny. To religious minds, recognition of that ultimate oppression leads away from economics, away from power games, utopian delusions, and spectacle. Directed toward the meaning of temporal existence, meditation on pandemic opens entirely to the ineffability of God, immutable and eternal.

In Francis such reflection opens, in the end, onto a perverse secular ideology. No papal prayers ascend in objection to the malevolence and systematic deceit of the Chinese Communist Party which wreaked this latest China-born infection on the globe. The Vatican declines to lead us in prayer for the conversion of China as, once upon a Cold War, it prayed for the conversion of Russia.

Addendum: In Laudato Sí, Francis wrote that the earth “now cries out to us because of the harm we have inflicted on her by our irresponsible use and abuse of the goods with which God has endowed her”. His Amazon caper spoke of “the cry of the earth” and “the cry of the Amazonia.” Attributing to the natural world emotions and a capacity to make judgements on human behavior is a tenet of radical environmentalism. It is alien to Christianity. (Melanie Phillips asks: Is the pope a pagan?)