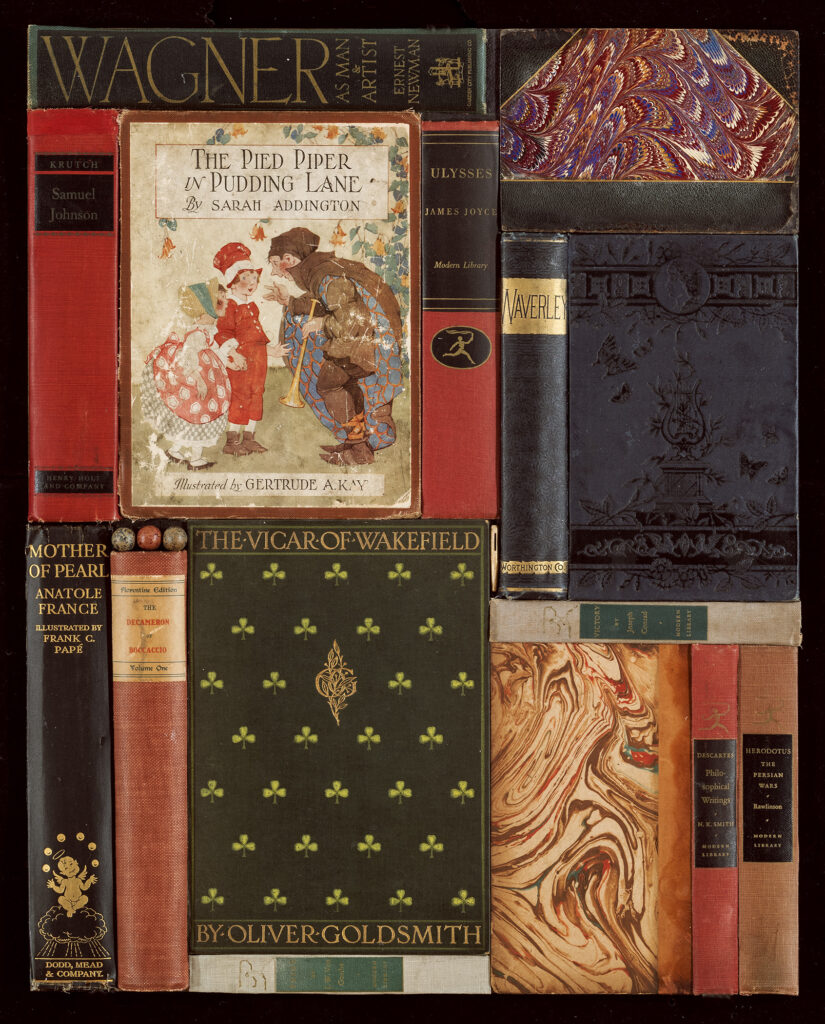

Holidays are for reading. Everything slows on a three-day weekend. It gives us time to read those titles that call to us as we rush past them on an ordinary day. That’s the old reading technology, the kind I love to surround myself with. Then come the blog posts waiting at the bottom of a string of bookmarks in one browser or another. In some respects, the greatest urgency attaches to these. They exist in the ether and might not be there when I want them.

Listen to Martyn Lyons, an Australian historian. His A History of Reading and Writing (2010), subtitled In the Western World, devotes a chapter to readers and writers in the digital age:

The internet is a mixed blessing. It has no memory and a huge amount of material disappears without being archived. The computer scientist Jeff Rothenberg joked, “Digital documents last forever—or five years, whichever comes first.” In fact, 70% of all webpages have a life of less than four months. Hardware and software rapidly become obsolete, so that data recorded on a 5 1/4-inch disk (the ones which really were floppy), may now be definitively irretrievable.

Preserving the past in a digital era is far less assured than we like to think:

Historians, incidentally, have to date been reluctant to accept responsibility for digital archiving: this looks like someone else’s problem, and it will certainly involve other people’s money. The Internet produces a surplus of ephemeral trivia dominated by “presentism”—the need to be new and up-to-date. Although its reach is instant and global, it threatens to entrench a new form of illiteracy, discriminating not between those who can and cannot read, but between those who have access or not to its tentacular web of communication.

The Internet encourages a kind of fragmented reading in which the reader rushes distractedly from one short item to another.

One sentence above should have stopped after the phrase “a new form of illiteracy.” Literacy is regressing here at home and among kids who carry smart phones that spell for them when they text. This October, Education Week described the historic lows in national math and reading scores:

Results for students who took the test in spring 2022—the first main National Assessment of Educational Progress administration for these grades since the pandemic began—show the biggest drop in math performance in 4th and 8th grades since the testing program began in 1990. In reading, 4th and 8th graders likewise are performing on par with students in the 1990s, and about a third of students in both grades can’t read at even the “basic” achievement level—the lowest level on the test.

Academic declines on NAEP were sweeping, spanning low-income and wealthier students, boys and girls, and most racial or ethnic groups in both subjects and grades.

Lyons referenced “fragmented reading” thirteen years ago. That was before entire populations carried an iPhone everywhere but into the shower. The fragmenting is worse now. Note the recent addition to online headlines: those added riders that tell how much eyeball time we will have to spend on reading whatever article we clicked on. Here, a five-minute read. There, a seven minute read. Oh hell, a 13-minute read! It is a great subject, but who has the time for it? Keep scrolling.

Who is served by these estimated time alerts? It is not the reader. Cautionary clocking works against the kind of engagement required for close and sustained reading, especially about things that matter.

• • • • •

Close in time to Lyons’ History, Mark Bauerlein’s The Dumbest Generation (2009) appeared. It is a discomforting insight into technology’s baneful effect on young people. A chapter on online learning—and unlearning—includes disturbing quotes by Jakob Nielsen:

• A site that demands close attention to words sends them packing, for the simple fact is “Teenagers don’t like to read a lot on the Web. They get enough of that at school.”

• Using the eyetracker in successive studies . . . Nielsen has reached a set of conclusions regarding how users take in a text as they go online and browse, and they demonstrated that screen reading differs greatly from book reading. In 1997, he issued an alert entitled “How Users Read on the Web.” The first sentence ran, “They don’t.” Only 16 percent of the subjects read . . . linearly, word by word and sentence by sentence.

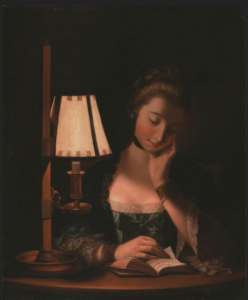

A Dangerous Recreation

Such is the subtitle of Jacqueline Pearson’s Women’s Reading in Britain, 1750-1835. Late eighteenth century epistolary novels—e.g. Rousseau’s Julie, ou la Nouvelle Héloïse (1761); Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa, or the History of a Young Lady (1748); Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774)—made readers feverish with empathy for characters in the stories. Emotional identification with fictional characters is a dangerous recreation. And it is still with us. Certain modes of invented encounter have simply transferred from the page to the screen.

In a loose but useful analogy, filmed soaps and their high-end cousins provide ongoing sagas of emotional entanglements. Drama series, police procedurals, sit-coms, even what we call “the news” script in the weepies where possible. Vicarious identification extends to crafted TV personas and sentimental abstractions (e.g. “the marginalized”). Add sobfests like “The Saddest and Most Emotional Interviews in Sports History” on YouTube. Not to forget popular emotional investment in celebrity relationships. (Poor Johnny Depp! Amber Heard was so cruel you want to cry!)

Yesterday’s read and weep is today’s watch and weep.

Richardson published Clarissa in the early years of the Age of Sensibility (c. 1740-1800). The heroine’s touching search for virtue persisted through nine volumes. A huge success, it was a printed-and-bound predecessor to our long-running TV series. (cf. 94 episodes of Sex and the City or nineteen seasons of Grey’s Anatomy.) The susceptibilities of readers in a culture that valued displays of sentiment were not so different from our own. Richardson’s friend and fan, Lady Dorothy Bradshaigh, wrote to him about Clarissa:

Would you have me weep incessantly? . . . I long to read it—and yet I dare not . . . in Agonies would I lay down the Book, take it up again, walk about the Room, let fall a Flood of Tears, wipe my Eyes, read again . . .throw away the Book crying out . . . I cannot go on.

Nowadays we have . . . what to call it?. . . the Oprah Winfrey effect. It is an audience-savvy pose that creates the impression of rising from the heart. And it moves audiences—particularly women—to tears. A premium on feelings and public emotional display attaches to every contemporary phenomenon from social media and teary politicians to conventional media wringing pixels over the psychological wounds of a murderer.

Human nature has not changed. Only technology differs. The ease and ubiquity of video and self-authored Internet content has democratized susceptibility to sentimental detours away from reasoned argument and analysis of issues. [Think of Zelensky pitching himself to the Cannes Film Festival and the Golden Globe Awards by video.] Streaming is simpler, quicker, than reading. We inhabit a colorized rewind of the Age of Sensibility that increases exponentially the reach and clout of dubious shapers of cultural consensus.

• • • • •

Contemporary virtue signaling—from media-driven grandstanding down to social justice lawn signs—is a latter-day means for displaying superior sensibilities. Richardson’s and Rousseau’s readers would marvel at the continuum.

Addendum

The day after “Readings” was posted Douglas Murray commented on a politician given to exhibiting how deeply she cares:

Farewell then Jacinda Ardern, the New Zealand Prime Minister who has announced that she is stepping down from office. In an emotional statement she cited burnout and said that there just wasn’t anything left in her fuel tank. . . . Ardern is an interesting type of left-wing politician. She is all about emoting, showing how caring she is and much more. Yet when it came to COVID lockdowns no government in the world was more authoritarian than New Zealand’s.