My recent post on Saint Catherine of Siena prompted several quizzical—not to say unhappy— letters. There seems a common conviction that Catherine’s title “Doctor of the Church” is long-standing. In tandem with that misbelief comes confidence that the very title refutes any claim that the saint was illiterate. Surely the scholarship is faulty!

Let us look.

“Doctor” is an honorific that ranks Catherine alongside the founding luminaries in the Church’s intellectual history: Saints Ambrose, Augustine, Gregory I, and Jerome. Because it grants her theological and doctrine significance equal to these four giants (plus some thirty other Doctors, including ones from the East), there exists the impression that her “doctorate” is a venerable tradition that goes way back.

But no. It is of quite modern vintage. Pope Paul VI conferred the laurel in 1970, some six centuries after her death in 1380. What took so long?

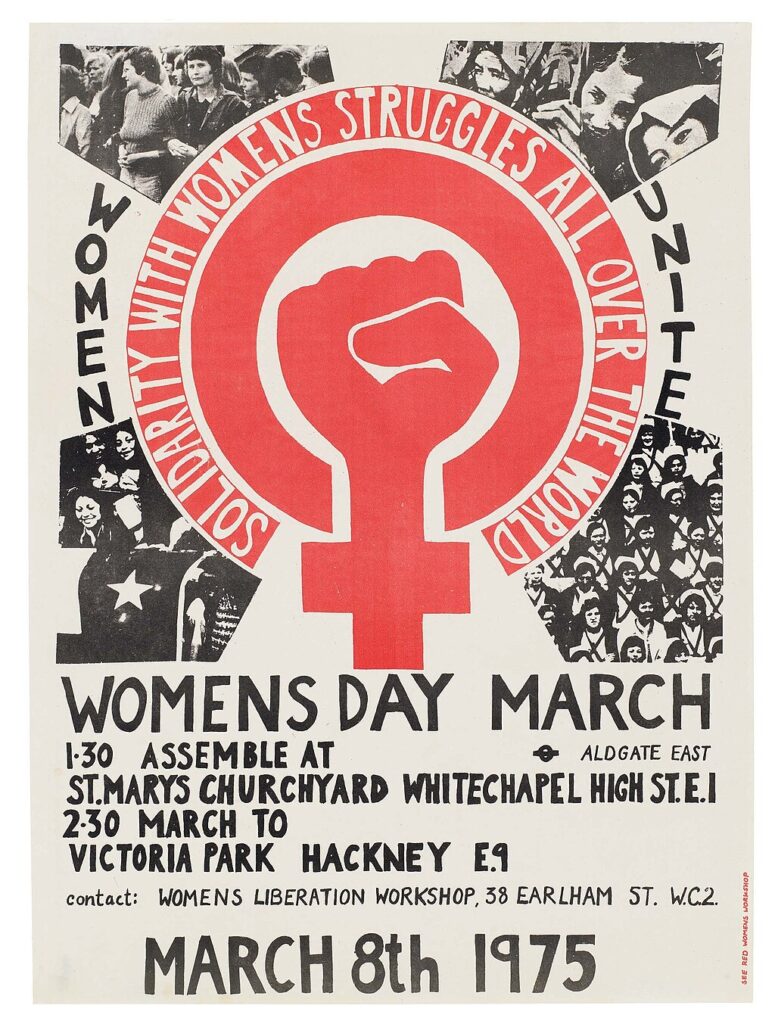

The seismic shock of the women’s movement sent tremors through Rome as it did everywhere else. Stress had been building since the nineteenth century. But not until second wave feminism burst on Western culture with a vengeance in the 1960s and ‘70s was there a tectonic shift in cultural mood. It was re-positioned away from male models to an ascendant female cult of its own. Here at home the venerables included Gloria Steinem, Shirley Chisholm, writer Susan Brownmiller, activist Bella Abzug, others. The United Nations decreed 1975 as International Women’s year. It has celebrated International Women’s Day ever since.

Simone de Beavoir’s The Second Sex had been sitting on Western women’s night-tables like Gideon’s Bible since 1949. Devotional reading expanded in 1963 with Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique. Translated into multiple languages—even Catalan—the book opened the eyes of well-off women in the West to their oppression under the tyranny of patriarchy.

What was Rome to do?

How could an institution ordered on an all-male hierarchy accommodate the moral temper of the times? How could the Church meet the moment without making changes in doctrine and disciple (e.g. women’s ordination)?

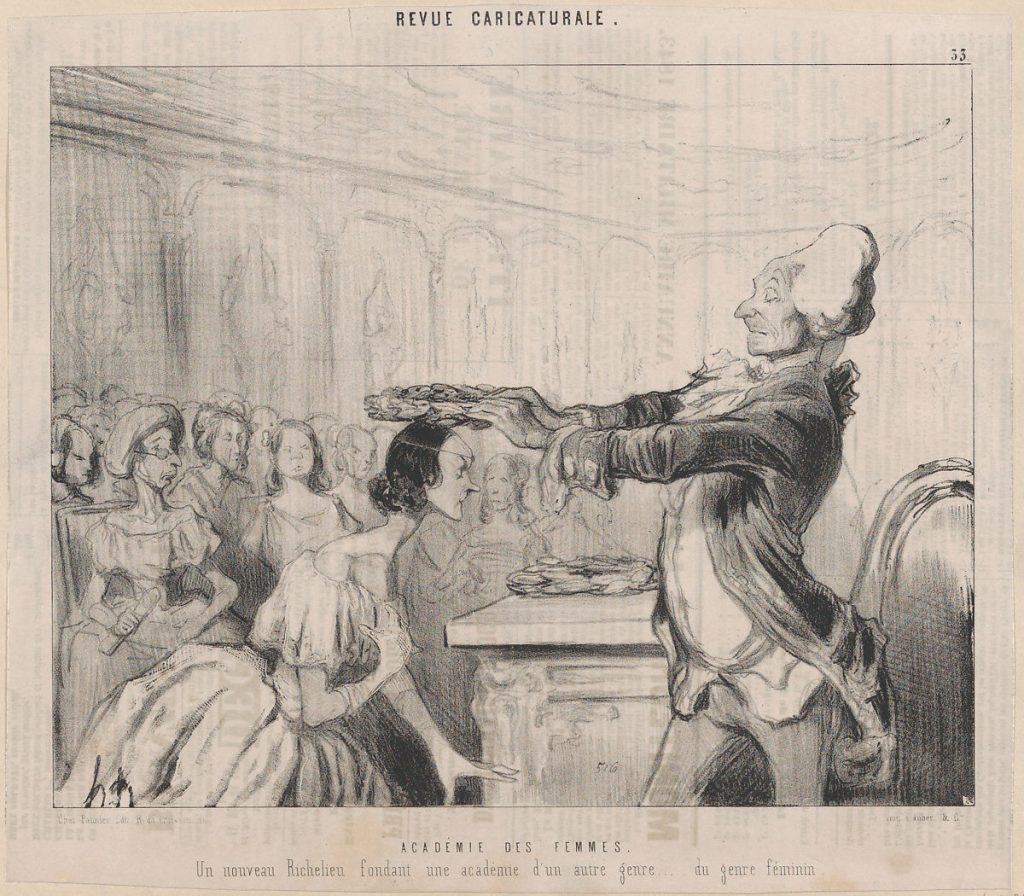

Reaching for steady ground, Rome adopted a strategy similar to that used by of art historians in the new dispensation. While art scholars scavenged the archives for women to add to the canon of memorable artists, Catholic scholars mined the Roman Canon for women with name recognition. It found four: Catherine of Siena, Hildegard of Bingen, Teresa of Ávila, and Thérèse of Lisieux.

The discovery was not presented as change. Instead, it was a smiling chance to correct a previous oversight—a supplementary, largely symbolic, retrofit of the record. In effect a defensive admission that recognition of the role of women in the Church was overdue, modern popes amended the record. In declaring Teresa of Ávila (d.1582) the first female Doctor of the Church, Pope Paul VI took care with his wording: “We have conferred . . . better yet, we have recognized the title Doctor of the Church for Saint Teresa of Jesus.” That was September, 1970. In October, he similarly recognized Catherine of Siena.

Recognition took a while longer for Hildegard of Bingen (d.1179). An educated, polymath and advisor to kings, she was canonized by Benedict XVI in May, 2012. Six months later, the pope declared her a Doctor of the Church. Thérèsa of Lisieux, the Little Flower of modern times, had been canonized already in 1925. Pope John Paul II, fine-tuned to the political utility of canonizations, seized the 1997 centenary of her death as opportunity to declare her a Doctor.

Each of these four women is rightly revered. We affirm their sainthood as anchors of mystery in the midst of secular drift. Their piety reminds us that, ultimately, faith demands that we to talk to God, not simply talk about Him. At the same time, I am uncomfortable with these retrospective “doctorates.” The timing of them stamps them clearly as genuflections to the women’s movement by men immersed in the Zeitgeist. And susceptible to feminist resentments.

Viewed in the light of the grandeur of the four traditional Doctors of the faith, these newly conferred titles look like grade inflation.

What is old is new again.

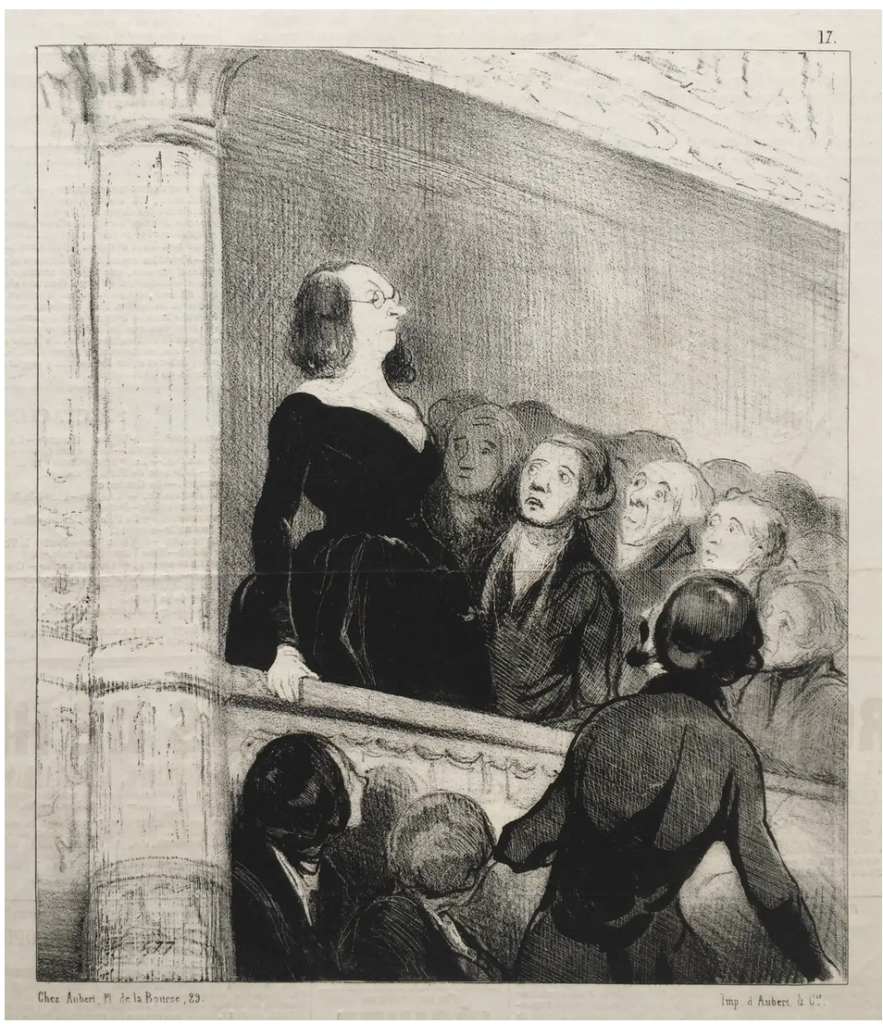

Men prominent in religious life (e.g., Raymond of Capua, among many others) set the terms for interpreting the burst of female mystics in the Middle Ages. The emotive character of female sanctity was embraced by reforming priests and monks as a divinely ordained countermeasure to male logic with its restrained, dispassionate emphasis on reason. Women’s visionary encounters embodied what Bernard of Clairvaux (d. 1153) later stressed as “the book of experience.” This meant a personal, ardent, other-worldly experience of Christ was considered close to being equal to the biblical exegesis and theoretical exposition that were the customary preserves of learned men.

Among medievalists, this phenomenon is sometimes called “the feminization of spirituality.” The celebrated temper of medieval holy women shed its Christological impetus over the centuries. Only the esoteric, cabalistic disposition remained. It became known in the twentieth century as “women’s way of knowing.”

That “way” carries with it an aggressive antinomianism that has done us little good, and much harm.

NOTE: Let me clarify what I meant by the phrase much harm. The phenomenon of “trans kids” is very much the creation of women. It is overwhelmingly mothers who discern the hidden truth of their youngster’s actual, physical sex. (I refuse to say gender.) The vaunted superiority of women’s intuition is touted as an evolutionary advance over tedious rationality. It trumps a birth certificate.

Through the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance, legend had it that only a virgin could tame the wild unicorn. Virginity lacks caché these days. And unicorns have been displaced by a more emotion-inducing species: the transgender child. Mythology has changed but “women’s way of knowing” carries on.