The sexual saga of Fr. Marko Ivan Rupnik, S.J., a priapic theologian, artist, and abuser of women, has gotten enough press. Now Catholics ask: “What should we do with his art?”

It is the wrong question. The only reason it arises is the infuriating fact that what should be done cannot be done. Punishment ought to be carried out on the man himself. Rupnik should be castrated. Unhappily, we do not do that anymore. So we fantasize about wreaking vengeance on his mosaics. Like them or not, they are innocent.

The better question is: Why is this stinkard not laicized? Feckless invertebrates in the Vatican rose on their hind legs to laicize (Fr.) Frank Pavone. But they drew in their claws with Rupnik. Expulsion from the Society of Jesus for a “stubborn refusal to observe the vow of obedience” is as vague an excuse as state-of-the-art casuistry could devise. And it is not laicization. He is still a priest. Not in the slammer where he belongs, he is still on the streets. Still free to prey on soft-headed women who, like one accuser, are “passionate about art.”

So long as there are susceptible women—ones who “come and go /talking of Michelangelo”— the Love Song of M. Ivan Rupnik will keep adding stanzas.

• • • • •

This from The Pillar is a disquieting read. It mentions Rupnik’s excommunication in 2019 for the canonical crime of abusing the sacrament of penance by absolving a sexual partner four years earlier. Prudently, he repented; the excommunication was withdrawn. Unsurprisingly, the retraction was a license to keep going.

The article begs the question: What woman would seek absolution from the priest who shtupped her? Testimony from the pseudonymous “Anna” suggests a clue. It reads like an improbable bodice ripper. Threesomes and then some? Erotic games? Art of the Kama Sutra? Apparently the adult Anna—in religious life at the time— lacked the early warning system of even an average twelve year old. An interview with Anna appeared in the Italian newspaper Domani this past December. It began with this:

“The first time he kissed me on the mouth telling me that this was how he kissed the altar where he celebrated the Eucharist, because with me he could experience sex as an expression of God’s love.”

More such revelations followed. The joy of sex, the mystique of art, and Ignatian discernment jumble together. The interviewer asked: “You didn’t find anything abnormal in his manner?” Anna responded: “Sometimes it seemed strange to me, but I explained it by his being an artist.”

If your parish uses missalettes with Rupnik’s work on its cover, you might understand why Rupnik’s lechery is more notable than his artwork. No one will ever say of him what Vasari wrote of Fra Filippo Lippi, that sublime Quatttrocento painter, Carmelite priest, and serial skirt-chaser:

Fra Filippo was so highly esteemed for his good qualities that the many other blameworthy things he did were compensated for by his rare talent.

Vasari catalogues those blameworthy things in The Lives of the Artists, the keystone of art historical literature:

It is said Filippo was so lustful that whenever he saw women who pleased him, he would give them all his possessions just to have them. . . . He was so obsessed with this appetite that when he was in such a libidinous humour, he paid little or no attention to the projects he had undertaken.

Working on a commission in the home of Cosimo de’ Medici, Filippo was too distracted by the object of his ardor to pay attention to the project. Cosimo had to lock him inside the house to get the job done. But after two days of quarantine, the friar “was driven by his amorous—or rather, his bestial desires” and escaped:

[He] cut up some sheets from his bed into strips with a pair of scissors, and, once he had lowered himself out of a window, he pursued his pleasures for many days. . . . Cosimo conducted a search for him and finally brought him back to work.

From then on Cosimo granted Filippo greater leniency: “And Cosimo always used to declare that rare geniuses are celestial forms and not beasts of burden.”

Artistic genius, a form of madness, could not be harnessed.

• • • • •

Was Rupnik taking cues from the Quattrocento? Apart from Savonarola’s brief spasm of influence, the moral laxity of late medieval and Renaissance artists is well documented. Dissonance between sacred subject matter and unprincipled or licentious behavior by artists stamped the age. Among Meyer Schapiro‘s eminent contributions to art history, was Art and Thought (1947). It reminded us of something that courteous art historians tended to avoid : “In an age of piety, one does not have to be religious in order to create a truly religious work of art.”

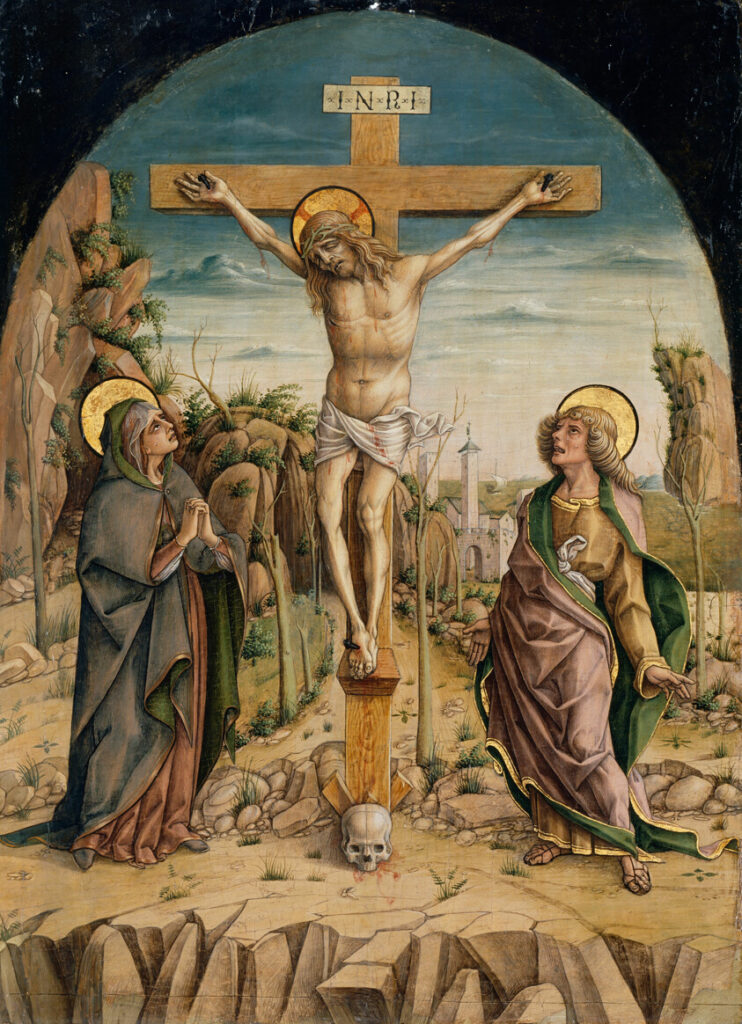

Of abundant cases in point, see Carlo Crivelli, creator of magnificent altarpieces and religious works. A young hothead in 1457, he was convicted, fined, and jailed for carrying off the wife of a sailor away at sea. He kept her concealed in his house “knowing her in the flesh in contempt of God and the sanctity of matrimony.” [Filippo Lippi’s taking of Lucrezia Buti from her convent comes to mind.] Still, his behavior had no bearing on his reputation as a painter. The numinous splendor of his work earned him a knighthood in 1490 by Ferdinand of Capua, later King of Naples.

Taddeo Landini (d. 1596), sculptor and architect, was much “loved and respected by Pope Clement VIII.” This, according to Giovanni Baglione writing about artists in 1692. Papal regard took no account of the sexual excesses that brought Landini such a “terrible pox” that “his nose dropped off.” Syphilis, rampant in Renaissance society, was “a certain disease” which accompanied the pastimes of artists.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio) died of plague in 1576. His son and pupil, Orazio Vecellio, died in the same year, also of plague. They are said to have frequented the same bordellos.

In sum, distaste for Rupnik is not a reason to de-install his art. Oscar Wilde said it best: “A man’s being a poisoner is nothing against his prose.”

In Rupnik’s case the poison—aesthetically speaking—is in the work itself. His bright, decorative graphic designs rarely compliment their architectural settings. The façade of the Basilica of Our Lady of the Rosary at Lourdes is all glitter and ice cream. Crowd-pleasing dazzle plays to sensibilities that confuse glitz with beauty. Here a quick thrill of misplaced gold leaf draws the eye away from the quiet beauty of the stonework. Grand in its austerity, the original building fulfills Rodin’s tribute to the great cathedrals of France as examples of “the great science of sculpture in the open air.”

With Rupnik’s mosaics in place, the current façade is a tribute to his connections in Vatican circles. He has won impressive commissions from prelates who see art through the lens of press releases and artists’ statements. The bureaucratic eye cannot see past an artful dossier.

What it can see are the practical benefits of commissioning a friend of Pope Francis to shine up the walls of prestigious tourist attractions.