By Heddy Breuer Abramowitz

THE AXIOM “THOSE WHO CAN, DO; THOSE WHO CAN’T TEACH” reveals an attitude of disdain towards teaching that reduces those who shape future generations to ones that haven’t made the grade. In art, it is more true to say that if one can’t do, it is unlikely that one can teach. Even then, not many artists are gifted at teaching. More than in most fields, in the art world one’s teacher is, in some ways, one’s pedigree.

Jerusalem’s quirky Barbur Gallery in the eclectic Nachlaot neighborhood is showing In the Finest of Company, an exhibit arising from the friendship between Francis Cunningham of New York and Pesach Slabosky. Originally teacher and student at the former Brooklyn Museum of Art School, the two evolved into close friends. Later, they were joined by Nomi Bruckmann, Slabosky’s Israeli-born wife, another former Brooklyn Museum of Art student and veteran art teacher at the Israel Museum’s Youth Wing.

Barbur, Hebrew for swan, evokes the story of the ugly duckling—an apt name for a gallery that started in a neglected urban spot. Now, five years along, it is a thriving, if off-beat gallery. Its founding partners combine community service—art classes for aging local residents, a community garden, and art history lectures—with a functioning gallery.

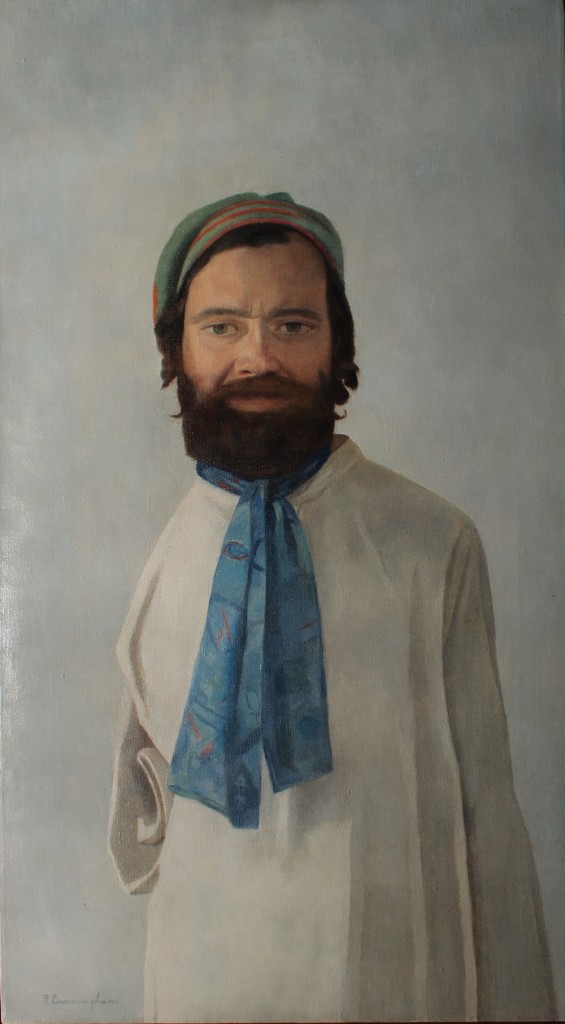

The exhibit spans a four-generation, teacher-student chain that starts with a work by George Grosz (1893-1959), on loan from a private collector. Cunningham studied with him at the Art Students League, where Grosz taught after emigrating from Germany in 1933. Cunningham is generously represented with five works, including a powerful 1981 portrait of Slabosky, made when the younger man was Cunningham’s student. The asymmetrical physique, a result of illness, is unsettling; yet a certain reserve, an emotional distance from the disfigurement, maintains the painting’s composure.

”

”

Unfortunately, not a single piece by Israel Hershberg is included here. Founder of the Jerusalem Studio School and a leading authority among representational Israeli painters, Hershberg had also been a Cunningham student. His absence is regrettable.

Slabosky, born in Detroit and living in Israel since the 70’s, is a well regarded artist in the Israeli milieu. He is a professor at the Bezalel Art Academy and, like Hershberg, he also a past winner of the Sandberg Prize. His Woman with a Drill, painted on a shaped canvas composed of canvas stretched across several profiles on which he uses thickly built-up oil paint, its density going beyond impasto. These are textured nodules in rough masses with found objects cobbled into it. Another painting is filled with crude symbols spaced across the canvas. Slabosky’s five works show his proclivity to an anti-aesthetic where beauty is not the goal, but the act of applying paint is.

In later years, Nomi Bruckman also joined Cunningham in painting expeditions. In this exhibit, she is the artist closest to him in artistic sensibility. Her self-portrait—a three-quarter profile documenting every nuance of her aging face—together with several interiors show her to have absorbed Cunningham’s approach to carefully observed studies.

The partners in Barbur Gallery, all former students of Slabosky at Bezalel, have disparate interests and approaches. Yanai Segal’s bold Red Flowers in a Decorated Vase leans heavily towards childlike representations in simple colors. Masha Zusman’s imaginative Demon is painted on a found piece of peeling veneer; and Flower, suggestive a la Georgia O’Keefe, is worked on a piece of exposed photographic paper. Avi Sabah is impatient with the limits of two-dimensional painting. In Bermuda, seemingly accidental swirls of black and red paint form a sea that holds copper metal boats on a round support. In another Bermuda variation, he cuts black cloth into a shape resembling a pair of shorts and applies triangular ochre brushstrokes to it. The piece is hung unstretched.

Cunningham’s down to earth nature, his great concern for the value of painting and his encouragement of his students have left an diverse progeny in his wake. The pebble thrown by a teacher into the proverbial pond ripples widely and sometimes lap at unforeseen shores.

This pluralist exhibit illustrates the hodge-podge of currents among adherents to opposing art theories. While the elders engage in work grounded in accumulated and hard won practice, the younger artists apparently have chosen to jettison their training. They embrace more non-traditional materials, lighter avenues of pursuit and convey discomfort with the boundaries of two dimensional painting.

One wonders what Grosz or Cunningham (who could not travel for the exhibit) would make of their artistic descendants.

”

© 2010 Heddy Breuer Abramowitz