After hearing my confession, a gentle, elderly priest granted absolution and, for my penance, imposed the chaplet of Divine Mercy. I cringed. Oh, please, not that! Like the bargaining murderer in Alfred Hitchock’s I Confess, I negotiated the penance. I blurted out something about revulsion for the self-regarding jumble of Faustina’s supernatural stenography. I wanted nothing to do with the cult of Faustina and her preposterous painting commission. Please, Father, give me a different penance.

A mild man, he obliged. He rescinded the chaplet and sent me to the rosary instead. Thinking about it afterwards, I realized that it had been a mistake for me to balk. Reciting the chaplet would, indeed, have been a true penance, as irritating as a hair shirt.

Back in the confessional with the same priest some time later, I was sentenced again to a chaplet. This time I kept quiet and suffered my penalty.

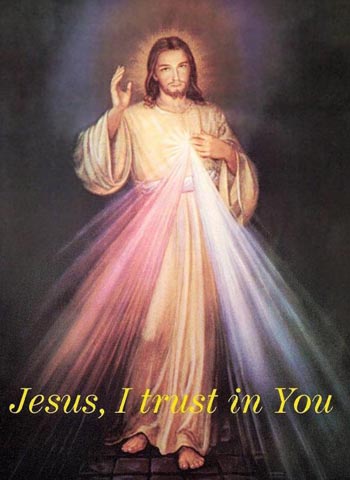

The Faustina phenomenon is a scandal to me. The language of the “mercy messages” and the content of her visions—not least that gauzy, epicene Christ figure—are alien to my sense of the sacred. I shrink from the devotion, and even more from the pious industry that built and sustains it. The entire edifice leads to the unwelcome thought that canonizations, like encyclicals, have become papal products manufactured for institutional reasons apart from—in tension with, if not in contradiction to—the deposit of faith.

• • • •

I believe in divine mercy, ache for it, with a whole heart. I rely on God’s pity for the fearsome reason that I believe in divine justice as well. Faustina’s visions conjure a feminized Jesus—a kitchen table Jesus drained of masculinity; one who feels, who talks about his feelings as a woman would. Worse, He Who spoke the universe into existence speaks to Faustina in the phrasings of a dime novel. Or an off-the-rack devotional tract.

Faith repels assent to Faustina’s Divine Mercy and the hackneyed astral fetish that expresses it.

• • • •

The Christ Who bled His humanity out on a jagged timber is distorted, made grotesque, by the imaginings of an overwrought aspirant to sainthood—a woman who envisioned herself Jesus’ secretary “in this world and in the next.” As Jesus’ personal secretary, Faustina gained a leg up on Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.

• • • •

Missing from Faustina’s Diary is all hint of that humility rightly associated with an experience of the sacred: “My sanctity and perfection is based on the close union of my will with the will of God.” (Diary 1107) What holiness is there in presumption?

The swagger continues in an unseemly ambition to best her competition in the sainthood stakes: “My Jesus, you know that from my earliest years, I have wanted to become a great saint. That is to say, I have wanted to love you with a love so great that there would be no soul who has hitherto loved you so.” (Diary 1372)

Not just a saint, but a great one—the kind that is remembered and fêted? And no other soul so loving? Not even the woman who gave birth to Him or those who walked the earth alongside Him? If this is sanctity, there is a helluva lot of chutzpah in it.

• • • •

Maria Faustina Kowalska [born Helena] of the Congregation of the Sisters of Divine Mercy experienced her visions between 1931 and her death seven years later. She was deemed delusional or unbalanced by those who knew her most intimately: her fellow nuns, her Mother Superior, and her early confessors. But once the gears of myth-making begin to turn, skepticism is ground to dust. Good sense and the gleanings of familiar observation are dismissed as ignorance or inattention. Jesus’ rebuke to the Galileans is forgotten. Persistent lust for signs and wonders overrides the Gospel warning against them.

• • • •

Jesus of Nazareth hid from those who would make him king. What are we to make of a vision in which He declares Himself “King of Mercy” and commissions a portrait of Himself like any profane crowned head?

• • • •

Ignatius of Loyola advised his followers to steer clear of women: “All familiarity with women was to be avoided, and not less with those who are spiritual, or wish to appear so.” The militant Ignatius, a “new soldier for Christ,” grasped something that we moderns in the West dislike admitting: A feminized Church is a weak institution. It puts soft devotions ahead of the Cross.