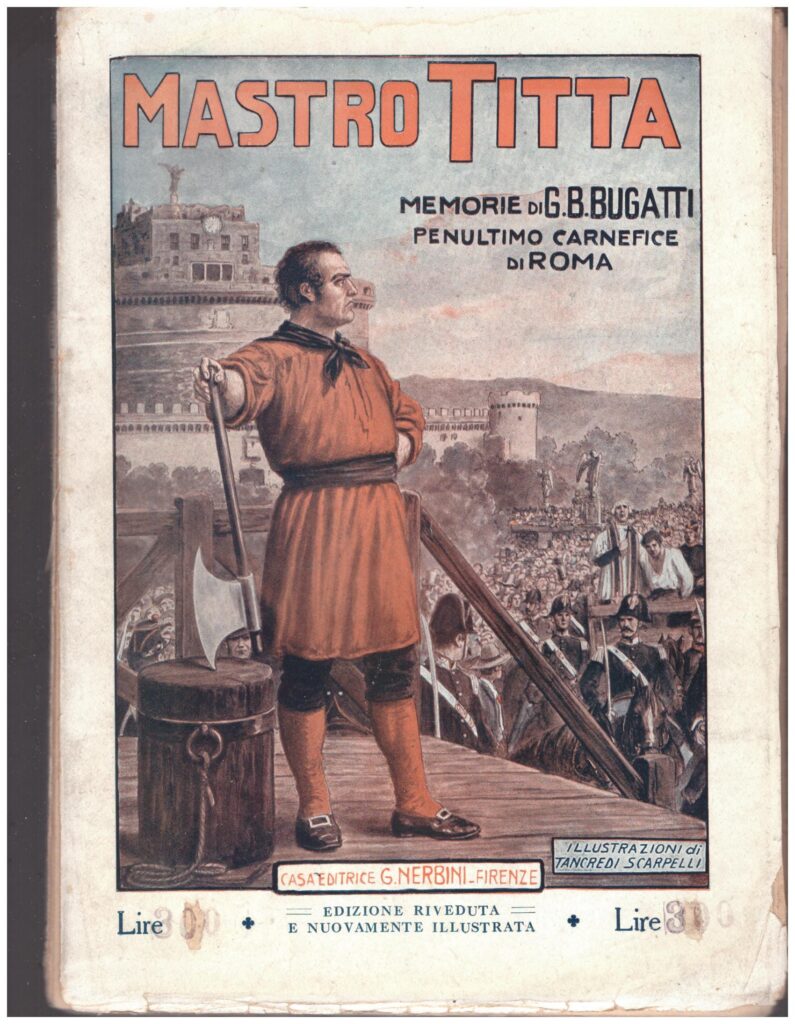

Meet Giovanni Battista Bugatti, official executioner for the Papal States from 1796 until he retired, with a papal pension, in 1864. Nicknamed Mastro Titta—a corruption of the Latin for “master of justice”—he was the longest serving and storied executioner under papal authority. He delivered justice 516 times over the years he held the job.

“With ax, noose, guillotine, Mastro Titta served the pope.” That enviable sentence is the opening line of “He Executed Justice,” an illuminating essay by John L. Allen, Jr., that ran in the National Catholic Reporter some quarter century ago. Allen wrote the piece as “a lesson in how fast things can change in the Catholic church, given that today’s pope [John Paul II in 2001] is a ferocious opponent of the act his predecessors little more than a century ago paid Mastro Titta to perform.”

In his time, Bugatti was a celebrity. Byron jotted a few lines about him in a letter to John Murray, his editor in England. Charles Dickens left a lengthy recollection in Pictures From Italy, after watching him work one afternoon in 1845. The Italian poet Giuseppe Gioacchino Belli penned several satirical sonnets in his honor. The most famous elegized Mastro Titta as a swift cure for a headache.

• • • •

Bugatti did not invent papal executions . . . . He never executed 18 people at once, as happened on Aug. 27, 1500, when thieves who had robbed and killed Holy Year pilgrims were put to death. (One was a hospital orderly, who had alerted his accomplice to weakened patients with deep pockets).

Nor did Bugatti work for Pope Sixtus V in 1585, when local legend says the pope’s “zero tolerance” crackdown on crime resulted in more severed heads on the Castel Sant’Angelo bridge than melons in the markets.

Before 1816, the method of execution was either the ax or the noose, and afterward the guillotine. In special cases, however, Mastro Titta would employ two other techniques.

The first was what the Romans called the mazzatello. In this case the executioner would carry a large mallet, swing it through the air to gather momentum, and then bring it crashing down on the prisoner’s head, in the same manner that cattle were put out of commission in the stockyards. The throat would then be cut to be sure the crushing blow killed, rather than merely stunned.

The other alternative was drawing and quartering. Sometimes this method would be employed in combination with the guillotine or ax. . . . In both cases, the point was to signal that the crime in question was especially loathsome.

In a home-spun version of deterrence, Roman fathers would bring their sons to watch Mastro Titta operate the guillotine: “By tradition, they would slap their son’s head when the blade came down, as a way of warning: ‘This could be you.'”

Paradoxically, in the era of Mastro Titta, Italy was in the vanguard of the abolitionist movement on capital punishment. Yet, as Allen writes, the Catholic church never participated in the effort: “The guillotine was busy up to the very last minute of the pope-king’s regime. Its final use came on July 9, 1870, just two months before Italian revolutionaries captured Rome.”

The Church exempted itself because Christian writers since the fourth century had defended capital punishment:

St. Augustine did so in The City of God. “Since the agent of authority is but a sword in the hand [of God], it is in no way contrary to the commandment `Thou shalt not kill’ for the representative of the state’s authority to put criminals to death,” he wrote.

Augustine saw the death penalty as a form of charity. “Inflicting capital punishment … protects those who are undergoing it from the harm they may suffer … through increased sinning, which might continue if their life went on.”

Aquinas followed Augustine in the 13th century in Summa Contra Gentiles. “The civil rulers execute, justly and sinlessly, pestiferous men in order to protect the state,” he wrote. The Cathechism of the Council of Trent, issued in 1566, solidly endorsed capital punishment as an act of “paramount obedience” to the fifth commandment against murder.

• • • •

This segment of Allen’s essay is key:

The leading abolitionists of the 18th and 19th centuries were Enlightenment-inspired critics of revealed religion. Popes defended their right to send people to death because to do otherwise seemed tantamount to abandoning belief in eternal life.

Catholic scholar James Megivern summed up the tradition this way: “If tempted to waver, one needed only to consult the bedrock authorities from Aquinas to Suarez. Questioning it could seem an act of arrogant temerity. If one did not believe in the death penalty, what other parts of the Christian faith might one also be daring or arrogant enough to doubt or deny?”

All of which makes the shift in thinking under John Paul II astonishing.

Allen continues:

Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, Pope John Paul II’s top theologian, says that Catholicism has witnessed a “development in doctrine” on the death penalty.

For a church that thinks in centuries, however, the word “development” hardly does justice to such a breathtakingly rapid change. It is more akin to a doctrinal revolution, one that would have dumbfounded no one more than the pope’s executioner. [emphasis mine]

Part of the reason Mastro Titta would have been flabbergasted is that a papal execution, as he experienced it, was a sacred act, rich with ritual and theological meaning hallowed by centuries of tradition. It was, in fact, a liturgy.

This gallows liturgy began with posting notice of an impending execution on Roman churches requesting prayers for the soul of the condemned:

The morning of each execution, the pope said a special prayer for the condemned in his private chapel. A priest would visit Mastro Titta to hear his confession and to administer Communion, symbolizing in the sacramental argot of the time that the executioner was fully christened by the church.

The execution was solemnized by a special order of monks, the Arciconfraternita della Misericordia, or Brotherhood of Mercy. The order was born in Florence in the 13th century, where it aided the needy and injured, and at one point numbered Michelangelo among its members. (Florence Nightingale, an Englishwoman born in Florence, was later inspired by the brotherhood to go into health care).

In the Papal States, the monks . . . delivered pastoral care to condemned prisoners and celebrated the rituals surrounding their deaths.

Underlying this liturgy was belief in execution as a form of expiation, a way for the condemned person to atone for evil done. The gallows stood as a daunting occasion of grace, “almost a sacramental.” St. Robert Bellarmine typified that piety in The Art of Dying Well, where he said of the condemned: “When they have begun to depart from mortal life, they begin to live in immortal bliss.”

• • • • •

The Lateran Treaty established Vatican City as an independent state in 1929. Signed by Benito Mussolini on behalf of the Kingdom of Italy under Victor Emmanuel III and Cardinal Pietro Gaspari for the Holy See, the treaty provided authority for the Holy See—the pope himself—to enact the death penalty against anyone attempting to assassinate the pope. The provision was never carried out, but remained in effect until 1969 when Paul VI quietly removed it.

In keeping with the times, recent Vicars of Peter have “discerned” a need to abolish the death penalty. A wonderfully plastic word, discernment. Its gnostic cast is disguised by being presented in terms of Newman’s theory of development of doctrine. The spirit of every age comes in like fog, an atmospheric vapor that beclouds distinctions between continuity and discontinuity in theological method and mind.

Allen’s term “doctrinal revolution” deserves more faithful attention than it has received.