The Twelve Days of Christmas are over. But the Christmas season does not end officially until Candlemas, February 2nd. That leaves time to revel in images that have delighted me all of my life. The magic of their pictorial agility never flags.

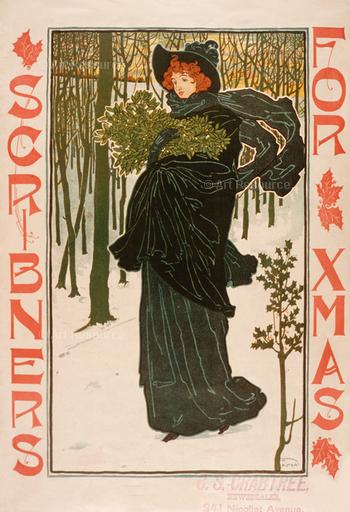

Their graphic intelligence—linear and compositional elegance, or what the old Italians called disegno—displays sensibilities that are rarely matched anymore in standard seasonal illustration. In part, that is because Christmas is no longer a spur, commercial or personal, to high imaginations. Talent drifts elsewhere. Also, grace of hand, long in developing, has given way to drawing software and to the photograph. An electronic mouse does not have the conscience of a trained hand. And a camera makes image production quicker and more facile than the mind’s eye—an organ which sees through the soul, unaided by a mechanical lens, unhurried by an impatient shutter.

But enough talk. Let us get on with images. All of these are secular, and for good reason. It is against the artistry and refinement of these non-religious images, made for a popular audience, that we can measure more vividly the diminuendo of Christmas in the larger culture.

What follows is an informal nosegay, florets in no particular order.

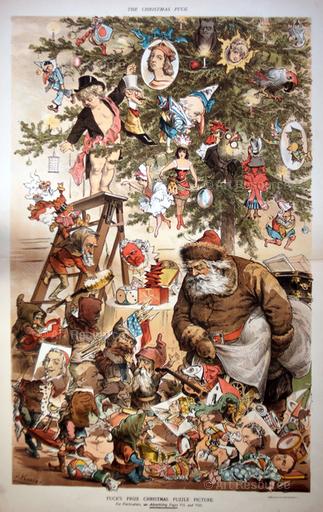

We tend to forget what Clement Moore told us in 1823: Santa Claus is an elf, “a right jolly old” one. He flies around in a miniature sleigh with eight tiny reindeer, an entourage far too small to transport the portly fellow we leave cookies and port for on Christmas Eve. The inimitable Arthur Rackham was one of the few artists who took seriously Moore’s lines. He had to. He was commissioned to illustrate the poem. Here is Rackham’s elfin St. Nick, looking mischievous, as an elf should.

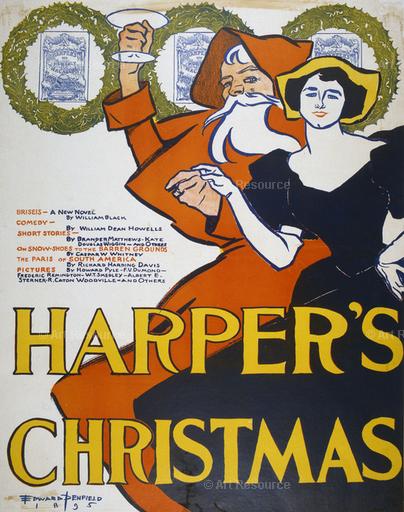

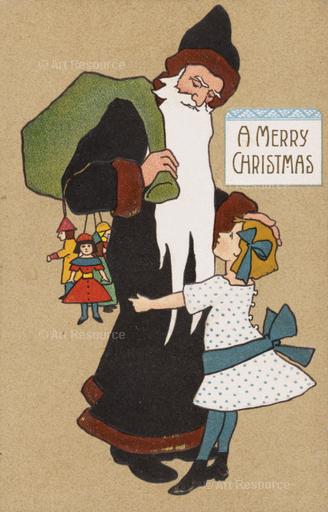

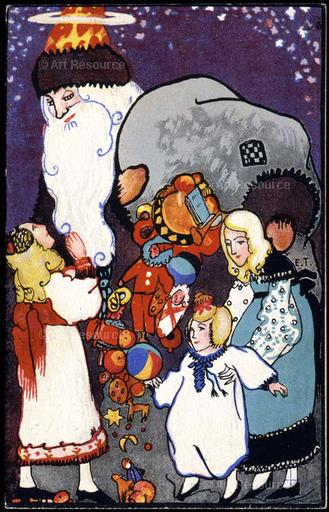

But people grew to prefer their Santa/Saint large and bulky, all the better to shoulder a generous cache of presents.

Father Christmas and Santa Claus have separate origins. One is a centuries-old personification of Christmas, the other claims St. Nicholas as an ancestor. But in the Anglophone world, they have become quite interchangeable. So I am happy to treat them as one and the same, certainly for the witchery each one elicited from some of the finest artists in the history of illustration.

One of my favorites is Walter Crane’s rendition of Father Christmas, trimmed in ermine, and riding a goat:

Wiener Werkstätte, the great Viennese design workshop, embraced holiday cards as a means of offering design excellence in an affordable medium. The unfailing inventiveness of its postcards were the vehicle for a solemn mission: evangelizing for aesthetic seriousness. Beauty counts as much in “minor” arts as in major.

Father Christmas did more than deliver gifts. He agitated for women’s sufferage in 1911. Later, during the First World War, he offered victory to the Allies and threatened a small, weeping (or sweating in fear?) Prussian with a birch rod. And, like any modern celebrity, he was once a popular product endorser—though he took no fee for his endorsement.

Images of women and children on cards or in prints—no Santa in sight—were common. And often uncommonly lovely.

• • • •

The last is for Grandma Mathilda, born in Mariesbad, southwest of Stockholm. She was a marvelous baker. Like the Swedish country girl that she was, she scoffed at gingerbread men. She baked gingerbread pigs instead, as her mother and grandmother had done back home.