Winding its way through Latin Mass circles is a clip from Brian Holdsworth’s digital evangelism. A Catholic convert in Edmonton, Alberta, and founder of Holdsworth Design, this entrepreneurial web designer understands the importance of branding as a marketing tool. Without putting too fine a point on it, evangelizing and marketing have something crucial in common. Both aim to make a sale.

Presentation is a bit stagey, from the Jesus-Christ-Superstar hairstyle to set design—guitars on the wall, swords in the corner, that armet on a shelf. Still, the analogy between modern branding and the distinctiveness of traditional Catholicism, especially the protocols of the Tridentine Mass, makes a useful point. Attached to those solemn liturgical formalities are psychological and emotional effects that bind us to the faith they represent. In a denominational marketplace, salesmanship matters.

Holdsworth argues for the Catholic “brand” by spotlighting the decline in other Christian denominations. Non-Catholic congregations continue to shrink while they try to rally the troops by stroking the Zeitgeist. By contrast, the Catholic Church should double-down on what marks its difference from the culture at large. Why else bother with Catholicism if it is just another ingredient in the spiritual soup? To renew the Church, keep to its trademark sensibilities—its rituals, devotional practices, music, and arts of worship.

There is truth to this impish pitch for the traditional Mass on retailing grounds. But brand recognition is only a partial truth; and not the most significant one. Attrition from the Church derives from much more than shortcomings in the Novus Ordo, by now the benchmark for most Catholics who show up on Sunday. More than variations in liturgical piety are at work in dwindling numbers.

Augustine’s famous comment applies here: “When Peter does it, when Judas does it, it is always Christ Who does it.” Ultimately, the single thing that matters is what the “brand” delivers—not its proprietary markers, not its packaging, but the sum of its aims. What does the Catholic brand serve? Toward what or Whom does it lead?

Despite use of religious language, the institutional Church has been gradually identifying itself—rebranding—as a this-worldly project. Its centrifugal push away from “My kingdom is not of this world” and toward utopian socialism predates Francis. He is speeding the Church toward the Omega of global governance but is not the origin of it. However conspicuous his demonization of fossil fuels and free enterprise, or his scaremongering over “catastrophic climate crisis,” the leftward trajectory of Catholic moral teaching has been with us for decades. It is a profound unmooring, perhaps greater than liturgical changes. The Latin Mass cannot renew an institution intent on self-immolating to secular gods.

Pope Benedict, Too, Contributed to Leftward Prompts

Even Benedict granted his name to utopian initiatives. To illustrate, revisit his third encyclical, the overlong “Caritas in veritate” (2009). It is seeded with elevated tropes that lend religious authority to authoritarian measures on a global scale: “build the earthly city”, “integral human development”, ” a new vision for the future”, and that sentimental fallacy “the human family.” It calls for “a new order of economic activity” that will “defeat underdevelopment”. This pipe-dream of universal social justice will lead to the “global common good.” It will do so on a “socially responsible and human scale.” This, despite contradiction between the iron hand of global bureaucracy and the fluctuations natural to human scale.

The encyclical smiles on “redistribution of wealth”, “redistribution of energy resources”, “redistribution governed by politics”, and “justice through redistribution.” The refrain of redistribution runs throughout, divorced from any conception of the exigencies of wealth creation. How and why does prosperity come to exist in the first place? Lurking within the rhetoric’s pious liberalism are suggestions that prosperity, if not a zero-sum game, is largely achieved by “improper means.” A dark hint hangs over references to the environment (“unregulated exploitation of the earth’s resources”) and to migration.

Read it in full; then wonder who actually authored it. The prose bears little relation to Joseph Ratzinger’s lucid theological writings. Effort to convey moral seriousness collides with an absence of substantial engagement with philosophies of economics. Its 159 footnotes cite only previous encyclicals—including Benedict’s own—or pontifical council documents. For all its pretensions to economic gravity, not one citation refers to the work of an economist or historian of economic thought. Instead, the text is clotted with high-sounding pronunciamentos untranslatable into real world policy. For example:

“Intelligence and love are not in separate compartments: love is rich in intelligence and intelligence is full of love.” [Emphasis original.]

Only persons can love. Systems, political parties, institutions, bureaucracies, and governments cannot. Love, as an emotion, is wayward; not reliably astute or wisely directed. Love understood as an act of will is shaped by ideology and, in statecraft, effected through bureaucracy. Force of one kind or another is implicit. Such love wreaks cruelties in its own name. History is a bloody saga of the ways by which the world loves.

Adopting a tone of magisterial competence, the encyclical instructs:

Economic science tells us that structural insecurity generates anti-productive attitudes wasteful of human resources, inasmuch as workers tend to adapt passively to automatic mechanisms, rather than to release creativity. On this point too, there is a convergence between economic science and moral evaluation.

Follow What Science?

Economics is considered social science because it does not fulfill the requirements of a science. Behind the paraphernalia of quantitative and qualitative methods, economic hypotheses and conclusions are inherently subject to politics. This includes the politics of language—language like this:

The continuing hegemony of the binary model of market-plus-State has accustomed us to think only in terms of the private business leader of a capitalistic bent on the one hand, and the State director on the other. In reality, business has to be understood in an articulated way. There are a number of reasons, of a meta-economic kind, for saying this.

That reads like something cribbed from a Davos manifesto. Meta-economics is outside the papal purview. Equally foreign to the purpose of the papacy is assent to political economics as the arbiter of “integral human development.” Chapter five informs the world that the “integral development of peoples” requires the “construction of a social order that at last conforms to the moral order.” At last. In other words, that and the World Economic Forum will finally rid mankind of the effects of Original Sin.

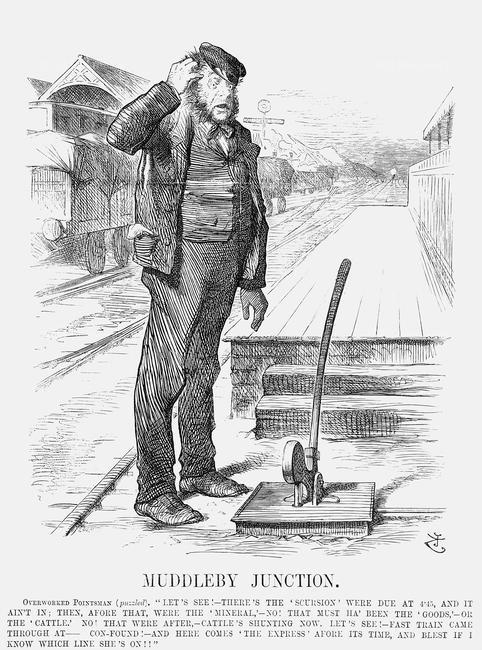

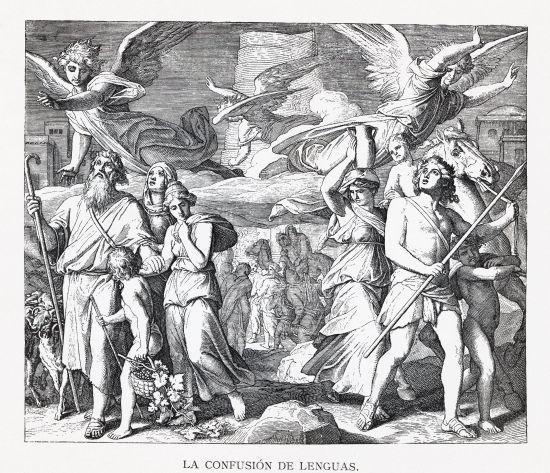

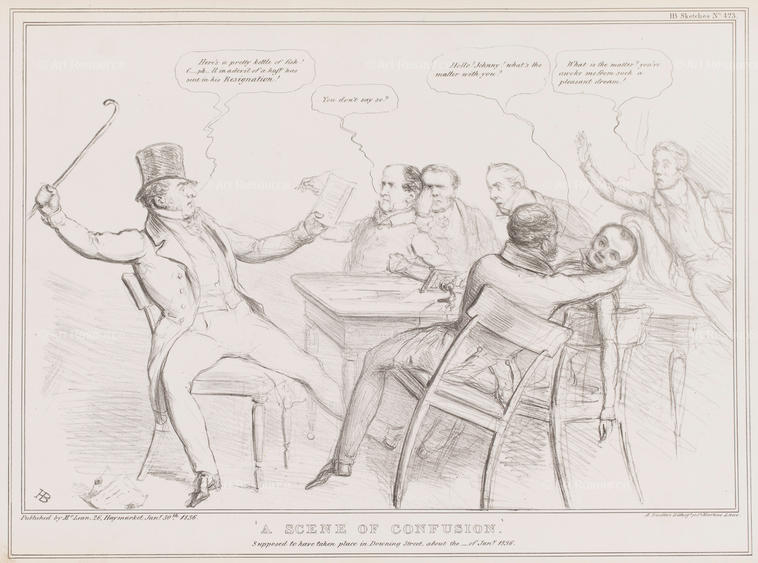

Where does this leave renewal of the Church? The Mass, whether traditional or “reformed,” remains at the center of the Church’s prayer life. But it cannot rescue the institution from a confusion of aims. Twenty-some ago James Schall, S. J., commented on that confusion:

Evil is come to be defined in primarily political terms, not in personal terms which relate to the natural limits of man . . . . The chosen people become the avant-garde party. The suffering Christ becomes suffering mankind. . . . The ongoing life of the species on earth replaces the doctrines of heaven and hell. . . . Redemption is the structural reordering of society, not personal conversion to the living God.

Once politics supplants grace as the institutional Church’s primary concern, renewal is a vacant concept.