Catholic televangelism is not what it was when Fulton Sheen pioneered it.

In the following clip from a 2023 segment of the Chris Stefanick Show, Ripperger appears authoritative, reasonable, and self-assured. It is the demeanor of a tenured prof holding forth in the faculty lounge. “Demons understand human psychology the same way St. Thomas does,” the prof intones.

That ought to have been a howler. But no. Chris Stefanick is dazzled at Ripperger’s facile equivalence between Thomistic theology and “cutting edge psychology”—neither of which he demonstrates any acquaintance with.

Watch:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IUnLoym0GOA

Rippberger’s smug confidence in his own judgment derives from his having been selected for this line of work by a demon itself. More precisely, God chose him but a demon confirmed the choice. Our exorcist confided this tidbit online in his Q&A with a star-struck Stefanick.

Resuscitating notions prevalent in the High Middle Ages, Ripperger lets on that demons are choosy about those they grapple with. They do not want to waste demonic power on also-rans: “The first priest before whom the demon preternaturally manifests . . . is the one Christ intends for the exorcism.”

The demons know that all the other priests—they’re not the ones that God has chosen. And very often it is communicated to them who the exorcist is who will boot them out. So they will ignore all the other priests and just hone in on the priest that they know. And they will react more to him than they do the other ones.

Wow! Stefanick is too awed to ask precisely how—by whom?—the demons get tipped off. In the tones of an ABC anchor leading Kamala Harris, Stefanick warbles: “You’ve very much been chosen by God for this work. And it was made clear to you through a demon!”

Yeah. Pretty much. . . . That’s true. That’s how you find out. . . . Part of it is also that . . . Our Lady kind of drugged [dragged?] me into it. . . . It’s a pretty clear indicator.

That overweening response is a pretty clear indicator of something unbefitting a priest entrusted with the care of fragile souls. Is Ripperger pitching for an entry in Butler’s Lives?

Ripperger’s self-created image as a technician of esoteric power and protocol is laced with vanity. To proclaim oneself chosen by God, by the Virgin Mary, and by some elitist hell-fiend with preferences—that’s a helluva curriculum vitae. It follows the pattern of hagiographic lore widespread in the Early and High Middle Ages. A demon’s preference was considered supernatural evidence of the sanctity of the exorcist.

One typical example from the twelfth century is Vita Sancti Erminoldi (The Life of St. Erminold). A Benedictine abbot in Prüfening, Bavaria, Erminold assumed the role of exorcist after a local priest failed to rout a demon. Mocking the luckless priest through the mouth of the demoniac, the demon declared: “I am not moved by your words or your chatter. I will save my exit for Erminold, for he has the powers to expel me.”

A demon’s ipsissima verba—its very words—is a hallmark of the trope. (Forgive me, but there seems something courtly, even unselfish, about a demon preserving its tenancy for a potent exorcist who will gain fame for success.)

Much is missing from Ripperger’s equation of demonic and Thomistic grasp of human psychology. The genius of St. Thomas, exceptional as it was, was also that of a thirteenth century man. He inherited from Aristotle and the physician Galen the humeral theory which held that four bodily fluids—blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm—determined a person’s temperament and behavior. Any imbalance in the humors led to certain sicknesses of body and mind.

The idea that these humors were connected to celestial bodies, seasons, body parts, and stages of life, were staples of the scientific thinking of Aquinas’s day. Thomas inherited the ancient belief that stars and planets played a role in the behavior of the physical world and in ourselves. He also accepted the conviction that full human life did not begin until ensoulment took place some 40-80 or so days after conception. Earlier for males; later for females. [All the same, he condemned abortion.]

Aquinas died before William Harvey’s 1628 discovery of systemic blood circulation, an anatomical revelation that presaged the waning of humeral theory. Aquinas had been dead six hundred years before an Augustinian abbot, Gregor Mendel, introduced the world to genetics and the hereditary effect of genes (which contribute to personality traits.) Neurology, still in its infancy in the seventeeth century, continued to expand in the twentieth. Knowledge of the nervous system and its intricate role in cognition, behavior, emotion, and memory, has bearing on the subject of possession that was inaccessible to Aquinas.

• • • • •

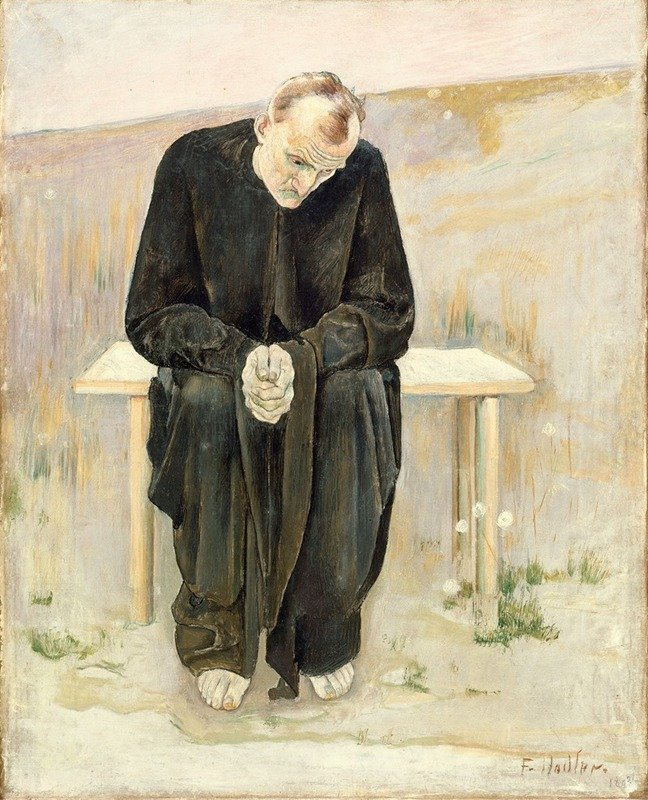

It is not my intention to foreclose belief that demons exist and can inhabit bodies. Not at all. It is simply that everything in me shrinks from Ripperger’s self-congratulatory mien, his lack of reticence, and easy footing at the edge of that abyss in which roil the inner conflicts of anguished souls.

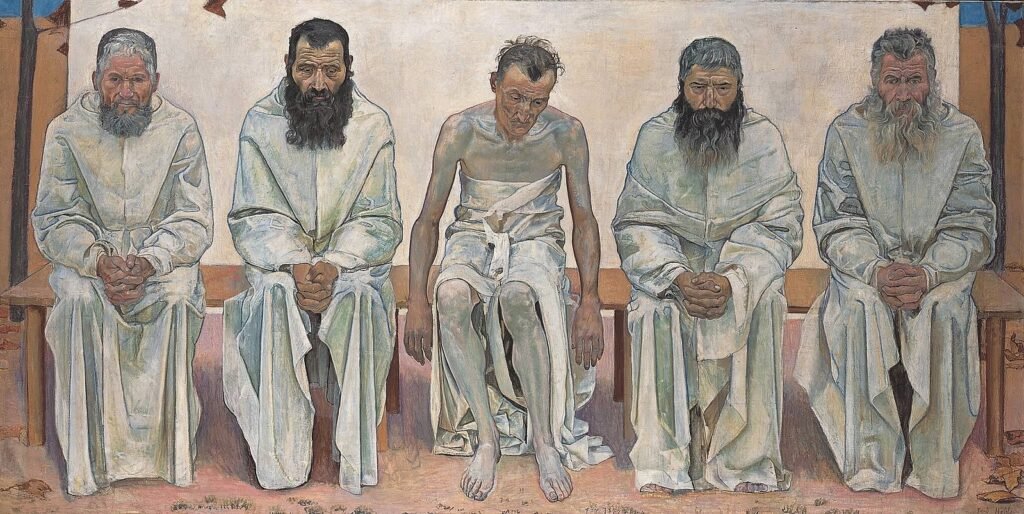

The poverty of language to explain the mystery of God and the human psyche requires deep humility in all who profess the faith. Equally so in those who do not. Ripperger exhibits none of the modesty—the grace of diffidence—appropriate to a man engaged in the complexities of human suffering. Or the enigma of evil.

Fr Louis Marteau, then director of London’s Dympna Centre (which counsels clergy and religious for emotional and vocational problems) submitted the concluding comment on a 1976 essay “Exorcism: A Psychiatric Viewpoint” in the Journal of Medical Ethics. Speaking as both a therapist and a priest, he wrote:

My own appeal is for humility. Those who work with patients with the troubled mind walk into areas of human darkness with little but their own faith to guide them. We know so little, we comprehend in so shallow a fashion that there is no reason for confidence in our own assumptions. For the sake of the people who put their trust in us, we must be open to our own limitation, to take care that where we do not help we do not hinder, and continue to grope toward the truth together rather than engage in wars of doubtful symbolism.

• • • • •

Gerard Manley Hopkins: “O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall /Frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed.”