Chief among the uses of enchantment is catechesis. The truth of that is made plain in Priscilla Smith McCaffrey’s Christmas Blossoms, a short story steeped in the mystery of the Incarnation. Suitable for all seasons, the protagonist’s deepening entrancement with the Nativity story resonates most sweetly at Christmastide.

Viewed from the vantage point of structure and intention, the narrative moves within the atmosphere of what might be called a Catholic fairy tale. Historically such tales were written for all ages, adults no less than children. And they do not necessarily include fairies. In fact, relatively few do. What they do create—in story form in lieu of an event—is fulfillment of Josef Pieper’s theory of festivity. The philosopher contended that “the artistic act is like festivity itself, something out of the ordinary, something unusual, which is not covered by the rules governing the workaday world.”

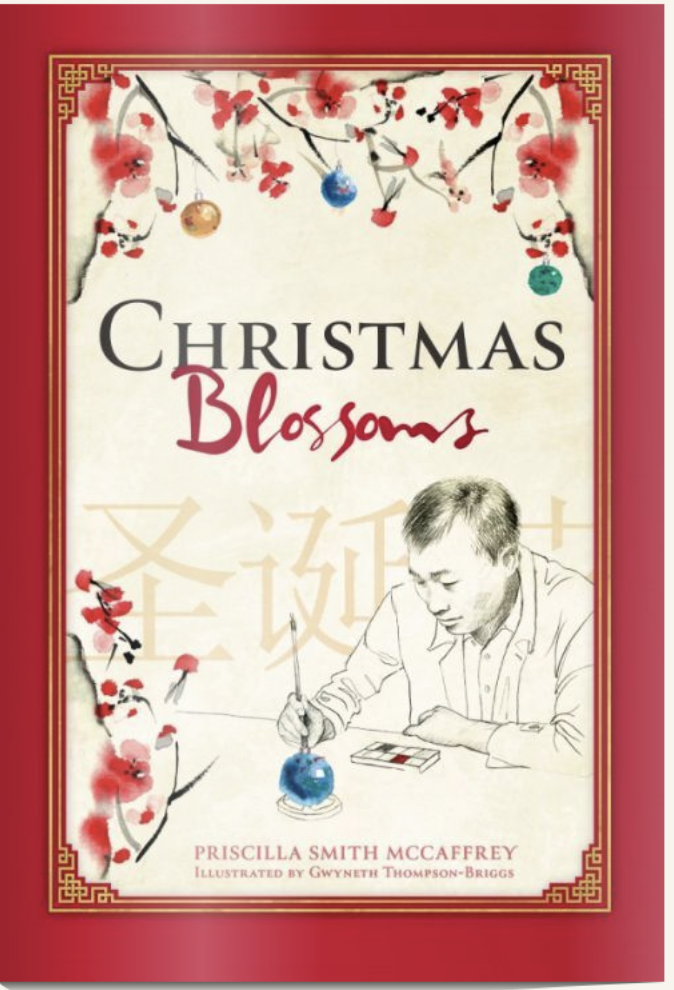

Just as celebration of the world lies at the core of festivals, celebration of the Incarnation is the innermost action—the heart—of this extended anecdote in the life of a fictitious Chinese artisan, Zhang Jian. A traditional mythic quest in contemporary dress, Jian’s story begins in advanced old age. His journey is an inward prompt to return to his ancestral home: the fullness of the Catholicism he knew as a boy.

Born into a Catholic family in China before the Revolution of 1949, Jian was familiar with Christian themes and symbols. While their significance had faded under the Communist regime, their imaginative appeal—the wonder of it—carried into adulthood. Gifted with a delicate hand, he earned his living painting glass ornaments, mainly Christmas decorations for export. By the time the story begins, the Party had turned a practical eye on Christmas. It was no longer condemned as a decadent season: “It had become business.”

That business, realized in the factory in which he worked, is the tale’s enchanted setting. In place of a charmed forest “where the sun shines and the birds sing,” is the Fluida Company in Tianjin, in the province of Hebei. The factory provides globes and baubles shipped to the West for consumption at Christmastime. Love of his own handiwork expands into love of its significance. Painted globes become metaphors for the magic of the Nativity theme he painted on them.

The loveliness of the ornaments stirs Jian’s memories of Christmases past. He remembers attending Midnight Mass hand-in-hand with his father. On the Christmas Eve central to this story, Jian finds himself “caught up in the mystery and enchantment of the night.” He enters the old cathedral—dedicated to St. Joseph, “protector of families”—as he did in his youth.

The loveliness of the ornaments stirs Jian’s memories of Christmases past. He remembers attending Midnight Mass hand-in-hand with his father. On the Christmas Eve central to this story, Jian finds himself “caught up in the mystery and enchantment of the night.” He enters the old cathedral—dedicated to St. Joseph, “protector of families”—as he did in his youth.

Each of his reflections carries a delicate lesson: “He came back from Communion with deep repose and calm. He had been truly fed; the open mouth in harmony was satisfied with the finest wheat. He was at peace.”

The Last Gospel echoes in the simple act of lighting a Christmas taper:

He reached for the candle he had saved for this night and set it on the window sill to proclaim to the icy world that a light had come to dispel the darkness.

But the darkness could not comprehend it. Neither would the darkness overcome it, though it was a lone flame.

An understated rationale for the venerable Latin Mass finds expression in Jian’s attraction to it:

He dared not go often, but when he attended the Mass of the Old Rites, he felt he was as close to his parents as he could be. He stood as they had stood, he knelt as they had knelt, he prayed as they prayed, and he bent his head with them in adoration. He was at Mass with them.

Lin Renshu, Jian’s non-Christian friend and coworker, serves as the necessary confidant to whom Jian can explain the Nativity: “Tonight he would explain more to Renshu; even if he failed in his explanations, it would bring him joy about the true meaning of Christmas.”

Renshu’s artless questions—e.g. “What are you thinking of my friend?”—elicit Jian’s responses which are the ballast of the tale. With no experience of Christmas, Renshu is inquisitive. “Why do you celebrate the birth of a little Jewish boy?” “ Why would the Chinese raise Him above their ancestors?”

Jian’s friends are bewildered. Is it reasonable for a good God to create a world in which bad things can happen? In his untutored simplicity, the old painter suggests: “He didn’t want the world to be better. He wanted people to be better.”

Children respond wholly and earnestly to stories. Precepts, propositions, and the dictates of academic argument come later. Christmas Blossoms, then, is a tender and intelligent introduction to the mystery of the Incarnation to young ears.

Christmas is more than a festive occasion. For Christians, it signifies the ground of festivity itself. Jian understood: “It’s an enchantment.”