Michael Quenot, an authority on the art and Orthodox theology of icons, insists on the primacy of two dimensional images in the visual expression of religious conviction. In The Icon: Window on the Kingdom, he wrote that the two-dimensional iconographic image is “more accessible to mystery.”

It is an irritating point to anyone who marvels at the possibility, attested to by modern physics, that we live in ten, possibly eleven, dimensions. We experience three of them—height, length, depth—directly through our senses. The fourth, time, is conceptual but its effects are visible. The possibility—no, the probability of more—is stunning. How can an image that shrinks the dimensions of reality to a mere two be more compatible with a sense of the sacred than Western art’s introduction of three-dimensional perspective, natural light and shadow? Are these pictorial devices not aspirations toward greater intimacy with reality? Contrary to Quenot’s claim that openness to transcendence fades with the introduction of the third dimension, is not the stylized, two-dimensional icon a reductive art?

Yes, it is. But perhaps that reduction is fuller, more expansive than we want to admit. After years of grappling with Quenot’s argument, I have stopped resisting it. Why? I do not have an intellectual explanation. I can only admit that this season of the liturgical year is responsible for some of the most godawful attempts to convey transcendence. This week’s feast of the Ascension of Christ, forty days after Easter, set me thinking of the preposterousness of so much Western religious painting.

By the best of hands, mind you. It is hard to keep the faith without shielding your eyes from images of Christ’s resurrection and ascension.

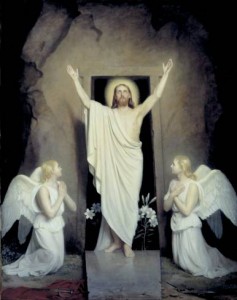

Typical of popular saccharine imaginings is a resurrection by Carl Heinrich Bloch (d.1890), a renowned Danish painter in his day. A prominent art critic of the time, Karl Madsen, chirped that Carl Bloch reached higher toward the great heaven of art than all other Danish art up to that date. It looks like a tableau vivant staged in a Fire Island bathhouse. This is camp before we had a word for it:

Titan’s great Polyptych of the Resurrection, is an infinitely superior image. A robust Christ, as solid as a hardworking tekton needed to be, floats upward like a leaf in the wind. A beautiful, earthy male figure trails a victorious flourish of drapery. Still, glorious as the painting is, it is a scene of levitation, not transcendence. Verisimilitude is a barrier to the expression of mystery.

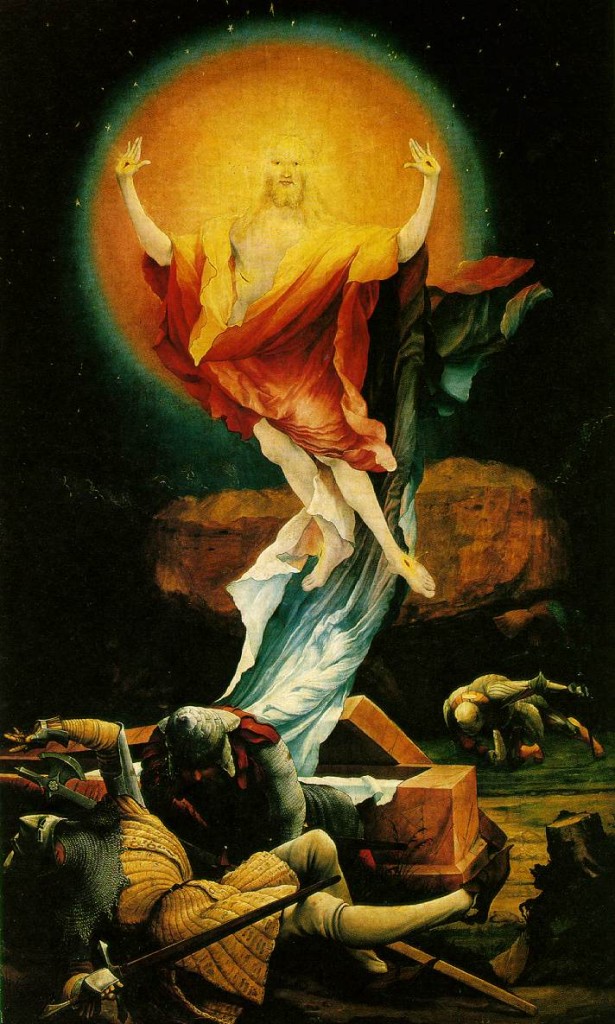

Matthias Grünewald created what is, arguably, the Western tradition’s most profound depiction of an event that, according to the Gospels, no one witnessed. His Resurrection panel for the Isenheim Altarpiece makes mystery palpable. Neil MacGregor, in Seeing Salvation, describes it this way:

And he not only shows us the miracle of the Resurrection, he compels us to see its significance. . . . We are made witnesses to the explosive triumph of light over darkness—and realize that neither death nor life will ever be the same again. The dead body we saw mutilated on the Cross, which still lies beside the tomb on the predella below, is raised and made glorious.

Grünewald aside, the Western canon tends to confirm Quenot’s judgment that the rejection of Byzantine traditions marked the beginning of a desacralization of religious themes. In Quenot’s words: “With newfound independence, sacred art ceded to a form of “religious art” void of genuine transcendence.

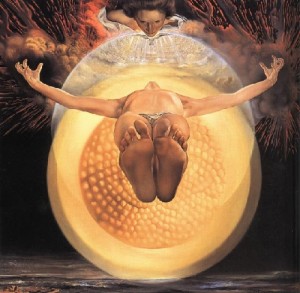

Dali makes a good witness for the prosecution. Herewith, his Ascension:

Christ is suspended in air as if headed into space on an invisible gurney. More of an entry into a CAT scanner than into time everlasting. In the end, it is hard to ignore Quenot’s belief that Western naturalism is no friend to man’s sense of the sacred.

Compare Dali with this icon of the Ascension. The panel is built on assent to hierarchy, to the ineffability of mystery and the imperatives of formal beauty. The ancient iconographers understood that, if eternity is to be witnessed in and through the icon, historic vicissitude in costume and taste could not apply. Some degree of hieratic stylization is necessary. Below, an image for the ages, its timelessness imbedded in geometry and the poetry of theological expression. Sacred function has little need of verisimilitude:

![]()

©2010 Maureen Mullarkey

NOTE: Another painter emailed a worthwhile comment on the subject of transcendence in painting vis-a-vis depictions of Christ:

In The Sexuality of Christ, Leo Steinberg maintained that a naturalistic depiction of Christ “posed no threat [to the mystery of the Incarnation] because these Renaissance artists regarded the godhead in the person of Jesus as too self-evident to be dimmed by his manhood.” (page 6) Though the depth of Christian devotion may be questioned in that era certainly, as secularity encroached, naturalism began to work against transcendent readings. Which is why, for modern believers, the Byzantine icon still has the force of conviction. I’m not sure it is simply a matter of 2D vs.

3D (2D can devolve into mere graphic design) but of the very strangeness of Byzantine image making; the way faces and drapery are rendered is so other worldly, alien even.