By Heddy Breuer Abramowitz

In a welcome move for a venue-starved city, the American Culture Center, an arm of the U.S. Embassy, inaugurated the first art exhibit at its library in Jerusalem. Entitled the “Memory Project I,” artist Robin Press presented an ensemble of prints dealing with childhood memories.

The opening included a talk by author Joan Leegant, visiting Writer-in-Residence of the Rudoff Graduate Program in Creative Writing at Bar Ilan University.

The American-born Press is no stranger to Jerusalem, having lived here for sixteen years. She recently exhibited “Memory Project” in her hometown, at Artspace Gallery in New Haven, CT. The project is a series of small prints that are longer on thought than on image

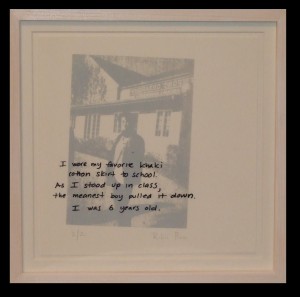

Press’ formula is simple. She invited various individuals to submit a brief reminiscence—two or three sentences—of an early childhood memory that had “marked” them. Each hand written recollection notes the contributor’s age at the time of the event. Each one is printed in black and super-imposed on a grayed ghost of the writer’s photograph in the here and now.

The library setting is an apt backdrop for this largely textual exhibit. These are go-with-any-décor, visually scant (or ‘pareve,’ meaning bland in local parlance) but attractively framed mementoes. Many relate to a past trauma, such as a first encounter with death, finding unfairness in teachers, leaving behind home for a journey to an unknown land, and the like. The prints are accompanied by audio loops of other memories. “My work,” says Press, “deals with the fracture in each of us.”

True, in our shared humanity, we all carry scars from the playground of life along the way. But is that enough? Is the mere statement of personal suffering sufficient as a work of art? Does it rise to the level of art by being placed on a wall? How does banality of language (“It was the first time I ever saw my big strong Dad cry.”) affect each component’s claim on art? While any memory can provide food for artmaking, does the bare exposure of a memory constitute art?

Leegant, a native New Yorker, bypassed direct entanglement with such questions, and talked, instead, about the tasks of memoir writing. Leegant gave a cogent description of the parameters—ethical and aesthetic—that any author, publisher, or reader of memoirs should bear in mind. Among these was a gracious caution against abusing the feelings of living persons, keeping a clear eye on issues of believability, avoiding unbearable violence or equally unbearable sweetness.

The reader is rarely engaged by a recitation of facts,” she said. “It is how the author uses the tools of language that turns events into something on a higher level, adding an understanding of a greater truth and achieving, in the turns of the prose, a work of literature.

Following Henry James’ dictum that an artist is one “on whom nothing is lost,” she emphasized “wasting nothing” and the close observation of life. “In the end, it is up to the author to locate meaning and turn it into something we didn’t already know, then it becomes art,” concludes Leegant.

Indeed.