Last month, in honor of the Vatican’s World Day for Migrants and Refugees, Pope Francis unveiled a three-ton shrine to migrants in St. Peter’s Square. Lumpen and inert, the addition is no surprise. Less and less is art conceived or promoted in terms of aesthetic value. It has become a form of advocacy journalism. Even in the Vatican, a repository of centuries of cultured achievement, political significance is the primary measure of artistic significance.

St. Peter’s spanking-new monument squats in proximity to the luminous twin fountains by Carlo Maderno and Gian Lorenzo Bernini. It has taken 400 years for the architecture of the square to accommodate popular taste for the mawkish. But now we have it: “Angels Unawares,” designed by Canadian artist Timothy Schmalz.

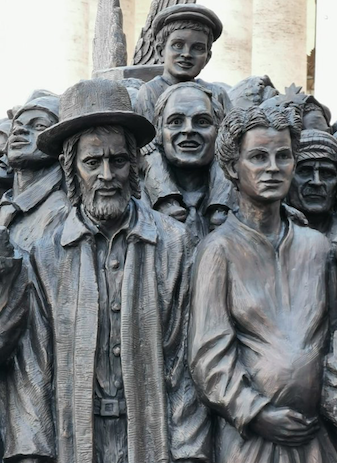

Have a look:

If ever any of the Vatican holdings should be transferred to UNESCO, this is the one. The thing lies on the square as out-of-place as a beached whale. Generic figures in symbolic ethnic costumes are packed together, herrings in a tin. In place of a pedestal, figures stand erect in a boat too small for their numbers, too shallow for an improbable clutch of upright passengers. But neither plausibility nor formal beauty matters here. What counts is the facile maudlin gesture, a mammoth 3-D emogi for audiences desensitized to vulgarity veneered with sentiment.

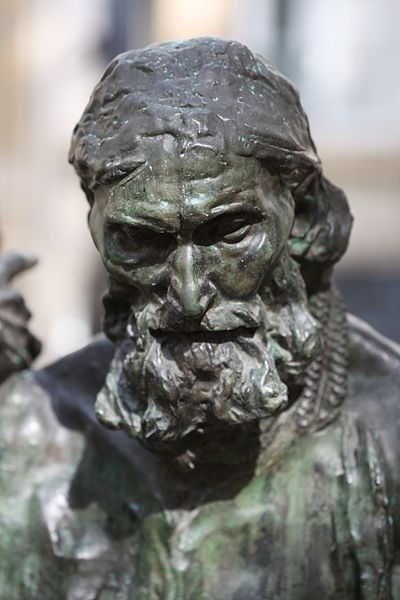

In looking at it, the first thing that comes to mind is its dependence on—and aesthetic distance from—August Rodin’s “Les Bourgeois de Calais” (The Burghers of Calais). The first monument to depart from the age-old practice of commemorating an heroic event with a single figure, Rodin’s sculpted composition was audacious in its time. His emphasis on an arranged grouping over an individual portrait has been used since to great effect. (Felix de Weldon’s “Iwo Jima Memorial,” based on Joe Rosenthal’s iconic photo of Marines raising the flag on Mount Suribachi, is one of the most familiar and compelling.)

The banality of Schmalz’s lumpen figuration, compared with the rigor and power of Rodin’s, suits the ideological incoherence of the Vatican sculpture:

Figures on the sculpture represent all historical eras and all cultures, and include a Hasidic Jew escaping Nazi Germany, a modern-day Syrian Muslim, a Cherokee man on the Trail of Tears, a pregnant Polish woman escaping Communism, and an Irish boy finding relief from the potato famine. There are ancient refugees from the biblical era, and others who migrated through Ellis Island to find a new home in America. An Italian immigrant carries with him a bag of food, suggesting that he and others brought life to the New World as they immigrated to America.

In the grab bag of history, everything jumbles together. The formal limitations of the Vatican sculpture are paralleled by the hodgepodge of incommensurate historical causes, conditions, and peoples divorced from circumstances. This Babel of selective ethnicities omits inconvenient ones. Where is representation of one million-plus Chinese peasants dispossessed to make way for the Three Gorges Dam? Where is a symbol for six million Venezuelans who have fled a socialist hellhole? Why a Syrian Muslim but no Christians?

Nothing in Schmalz’s make-believe boatload of formulaic stereotypes suggests any distinction between lawful immigrants, legitimate asylum seekers, and aggressive, often unscreened, illegal aliens. Nothings hints at a preponderance of young males of military—or jihadi—age. Why might that be?

Commissioned in 1884 by the city of Calais, Rodin’s glorious grouping commemorates the heroism of Calais’ town leaders in an incident at the beginning of the Hundred Year’s War. Jean Froissart, a contemporary of the 1346 event, chronicled the story. England’s Edward III laid siege to Calais. Victorious, he offered to spare the city’s people if their leaders would surrender. Edward demanded the men walk out of Calais with nooses around their necks and, in their hands, keys to the city and its castle. The mayor, Eustache de Saint Pierre, was the first to offer himself in surrender. Five other wealthy and influential men joined him in expectation of execution.

[In Froissart’s telling, Queen Philippa persuaded her husband to absolve the condemned men. Pregnant at the time, she feared their deaths would auger poorly for the child she was carrying. Whether that aspect of the chronicle is accurate or not—it is contested by some historians—the self-sacrificial valor of the six men is indisputable.]

Rodin commemorated the moral courage of men whose fortitude grew out of lives practiced in the habit of virtue. He worked in admiration of what Hemingway called “grace under pressure,” an aspect of character—an attribute of the soul—unbeholden to wealth or privilege.

Schmalz’ work, by contrast, derives from a downward cultural shift: the displacement of heroism by victimhood. Status as an underdog, a casualty of the past and the accidents of living, is what earns placement on a pedestal in St. Peter’s Square. Grievance (e.g. those Cherokees), mistaken for an endowment, passes as grounds for esteem.

Degraded motivation carries with it coarsened craftsmanship. Pay attention to the tender modeling of Rodin’s faces and the anatomical sensitivity throughout. Here are the virtues proper to the art of sculpture: its intuitive feeling for volume and mass, a tactile reciprocity between hollows and swellings—an energy—in the surface of the forms, the rhythm of planes and silhouettes.

Such concerns are what the old Soviets dismissed as “formalist hocus-pocus.” Schmalz was commissioned to create a propaganda piece, irrespective of its capacities as a work of art. Migrants and Refugees—a comprehensive, undifferentiated, impersonal category— are a maudlin abstraction useful in promoting globalist dreams.

Revivifying the canons of agitprop, art exists once again—as Krushchev asserted half a century ago—for the Party’s sake. The Party, this time, is what Jeffrey Sachs termed “Enlightened Globalization.” Francis, a globalist to the bone, is its high priest.

Redistributing wealth and peoples around the globe has been an aim of the U.N. for decades. Its paper on the 1976 Conference on Human Settlements stated: “Human settlement policies can be powerful tools for the more equitable distribution of income and opportunities.” The U.N.’s refugee-and-asylum intentions are aimed at the West, and at America in particular.

Jeffrey Sachs said as much in The End of Poverty (2005):

What then would be the focus of a mass public movement aimed at an Enlightened Globalization? It would be, first and foremost, a focus on the behavior of the rich governments, especially the most powerful and wayward of the rich governments, the United States.

This is the fundamental reason Sachs is embraced by the Vatican. Its long game extends way beyond the issues, however significant, that preoccupy the Catholic press.