When the U.S. government starts paying reparations to the descendants of slaves, let them begin with the Irish. White Cargo, co-authored by Don Jordan and Michael Walsh, two journalists living in London, was published in 2007. Drawing on letters, diaries, and court and government archives, the book earns its subtitle: The Forgotten History of Britain’s White Slaves in America.

The brutalities associated with black slavery in this country were inflicted previously on whites. It does not detract at all from the enormity of black suffering to note that poor whites suffered agonies in common with blacks. The institution of black slavery as the norm emerged out of white servitude, and was based on it. In Before The Mayflower (1964), black historian Lerone Bennett, Jr. wrote:

When someone removes the cataracts of whiteness from our eyes, and when we look with unclouded vision on the bloody shadows of the American past, we will recognize for the first time that the Afro-American, who was so often second in freedom, was also second in slavery.

As Jordan and Walsh note, indentured servant is the “deceptively mild label” applied to hundreds of thousands of men, women, and children shipped from Britain to America and the Caribbean in the century and a half before the Boston Tea Party in 1773. The authors track the evolution of the system in which tens of thousands of whites were “held as chattels, marketed like cattle, punished brutally, and in some cases literally worked to death. . . . According to contemporaries, some whites were treated with less humanity than the blacks working alongside them.”

That observation holds true, though it was not humane feeling but economics that marked a difference between treatment of indentured Irish and black slave labor. As property, blacks were valuable. A slave with a broken back or a shattered limb was a wasted asset. An indentured white, by contrast, was expendable.

In crude economic terms, indentured servants sold their labour for a set period of time; in reality, they sold themselves. They . . . were placed under the power of masters who had more or less total control over their destiny.

It has been argued that white servants could not have been truly enslaved because there was generally a time limit to their enforced labour, whereas black slavery was for life. [This discounts isolated acts of freedom manumission or self-purchase.] However, slavery is not defined by time but by the experience of its subjects. To be the chattel of another, to be required by law to give absolute obedience in everything and to be subject to whippings, brandings and chaining for any show of defiance . . . as were many whites, was to be enslaved. Daniel Defoe, writing in the early 1700s, described indentured servants as “more properly called slaves.”

Who were the indentured? White Cargo cites three main categories. Among the first were children:

Some were dispatched by impoverished parents seeking a better life for them. But others were forcibly imported. In 1618, the authorities in London began to sweep up hundreds of troublesome urchins from the slums and, ignoring protests from the children and their families, shipped them to Virginia.

This was presented by the English administrators as an act of charity to give “starving children” a new start. But in fact:

They were sold to planters to work in the fields and half of them were dead within a year. Shipments of children continued from England and then from Ireland for decades. Many of these migrants were little more than toddlers. In 1661, the wife of a man who imported four “Irish boys” into Maryland as servants wondered why her husband had not brought “some cradles to have rocked them in” as they were “so little.”

The second group of forced migrants from England were those the authorities wanted to be rid of—vagrants, prostitutes, beggars, and petty criminals. Quakers, too. Legal grounds were laid to empty England’s jails. Before 1776, some 50,000 to 70,000 convicts were shipped to Virginia, Maryland, Barbados, and other British possessions.

The third group was the Irish.

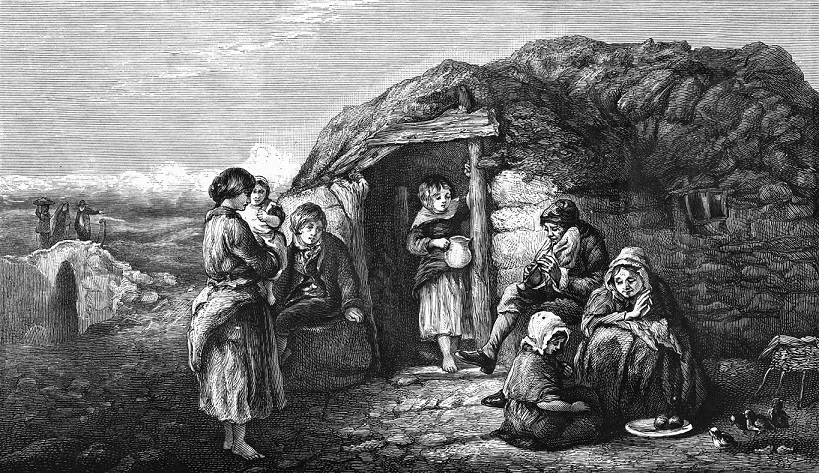

From the Anglo-Normans onward, the Irish were dehumanised, described as savages, so making their murder and displacement appear all the more justified. . . . Under Oliver Cromwell’s ethnic-cleansing policy in Ireland, unknown numbers of Catholic men, women, and children were forcibly transported to the colonies. And it did not end with Cromwell; for at least another hundred years, forced transportation continued as a fact of life in Ireland.

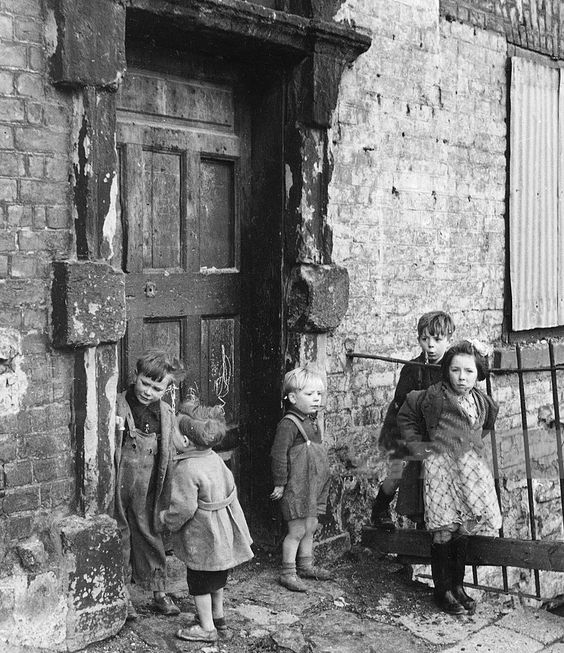

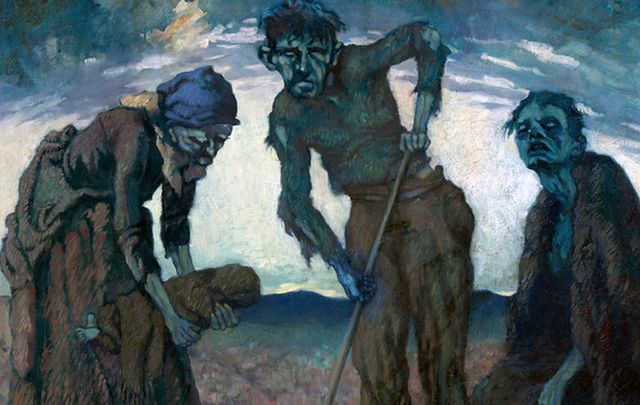

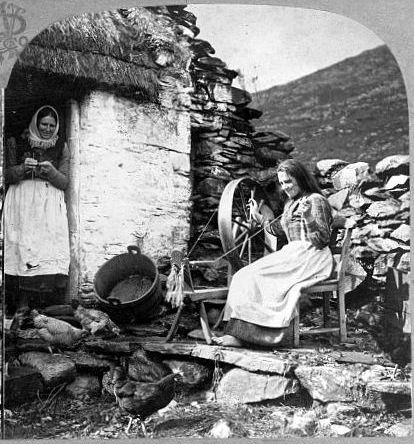

Note: The photographs above were obviously taken well after the colonial period. What makes them relevant here, however removed in historic time, is the little difference between conditions of Irish life in the 18th century on into the early 20th. Some years ago I met an epidemiologist with wide experience in hunger throughout the Third World. He had spent time in Ireland prior to the so-called Celtic Tiger, the rapid growth of Ireland’s economy in the mid-1990s. He told me that Ireland was the only country outside Africa where he saw children with the distended stomachs of the chronically malnourished.

Canal Diggers

A cursory paragraph on Irish labor in Connecticut has this:

The first discernible wave of immigration came in the early 1800s. Throughout the United States, the Irish dug. They dug canals in New York (the Erie Canal in particular) and in New Orleans. Connecticut had its own version: the Farmington Canal and the smaller Windsor Locks Canal, which was largely dug by Irish laborers in the 1820s. The Farmington Canal, which opened in 1828, would for a brief period become a vital part of the growing Connecticut economy.

Try to imagine great earthworks like the Erie Canal built by impoverished men with nothing but shovels and pick axes. No Bobcat excavator, no modern trench or rock cutting machine, no hydraulic-driven earth-moving equipment, no backhoe or bulldozer. Just an Irish immigrant’s body, one worth less than a slave’s in the decades before the Civil War.

Goodhousekeeping, explaining why Lady Bellum changed her name, defined the word antebellum this way: “While the original term wasn’t offensive, “antebellum” as we use it today glorifies a painful period in our history when Black people were enslaved by white people.” The exploitation of Irish labor is lost in this stock curtsy to half-history and identity politics. [Notice the difference in capitalization: upper case for one race, lower case for another.]

Germans and British also dug, but the Irish were the backbone of the migratory labor force that build our canals. They worked long days—at 37¢ to 50¢ a day. Added to the danger of the work itself was chronic risk of cholera and malaria.