My town hall boasts two flag poles. One flies the requisite Stars and Stripes. But it is the companion pole standing next to it that stirs the local blood. This one flaunts the colors dearest to a well-appointed community that congratulates itself on its civilized progressivism. Ukraine’s bicolor tops the second pole. It is paired with the rainbow colors of the LBGTQ Nation. The duet proclaims the town fathers’ common purpose: celebration of those chic causes that thrill The Better Sort.

Of the two flags, stay awhile with the Ukrainian one. It signals the enthusiasm of insular cosmopolitans who root for a war as if it were a soccer match. It is a great game, these playoffs. Zelensky is the boy wonder competing for the World Cup. Businesses in town display signs by the cash register: “We stand with Ukraine.” No matter that Ukraine ranks high on the roster of states that stink of rot. Never mind the distance between the myth of a plucky bastion of democracy and the reality of an authoritarian, oligarch-driven regime. It is the home team, by god. Our team colors are blue and yellow.

Putin is the designated maniac, an unstable tyrant on the phone to Stalin’s ghost. Or so we are coached to believe about a conflict fused at the hip to two decades of provocations by our own government and NATO. Christopher Caldwell has a useful essay in the Claremont Review on the going narrative:

Putin certainly had reasons to wish Ukraine kept in Russia’s sphere of influence. But in most Western accounts of what led to the invasion of Ukraine last February, these reasons are presented as psychopathological, not geostrategic.

Warhawking and bad thinking

It is not necessary to condone Putin in order to recognize a correspondence between the mainstream portrayal of him and the four-year-long demonization of Donald Trump. It is a dangerous inversion. One narrative reflects the other in a distorted glass. Caldwell cuts to the peril of our house of mirrors:

But the worst thing about this psycho-moral approach to Russian-Ukrainian affairs is that it produces bad foreign-policy thinking. It implies that, once you account for Putin’s personality, the war is actually about nothing—at least nothing political. And if the war is about nothing, then there is no need to consider what brought it about or where it might be going.

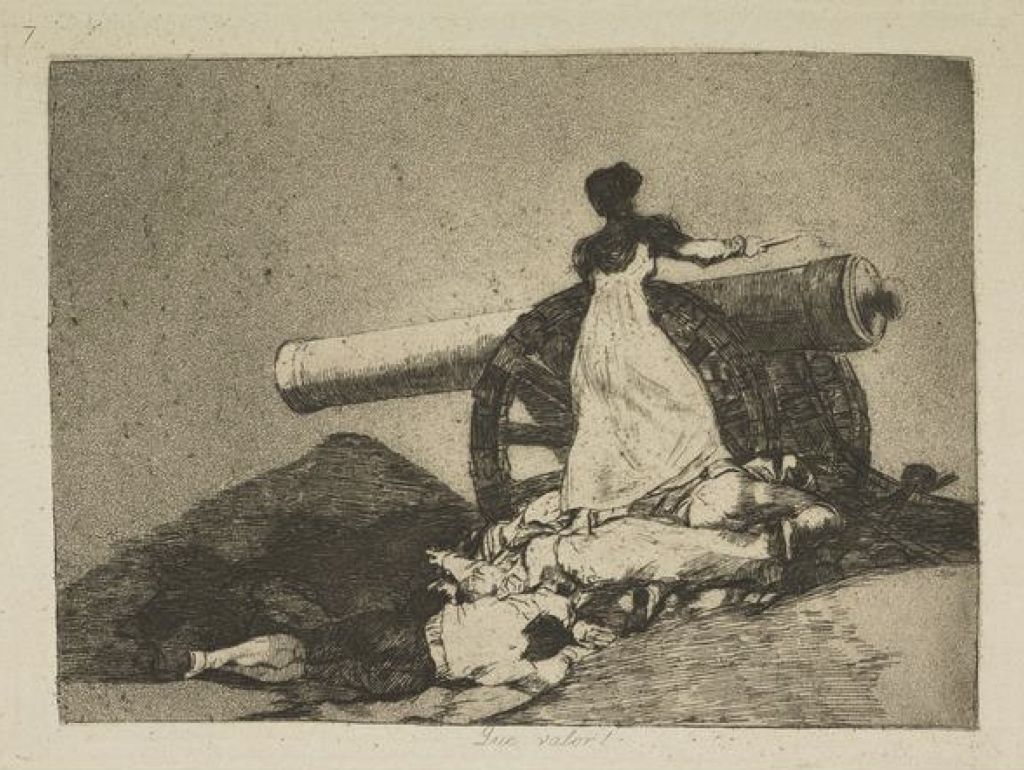

Concern for where it might be going points back to the war poetry of Wilfred Owen and Randall Jarrell. Men of two different generations in two different wars, each produced searing work that remains a cautionary bequest to heedless beneficiaries.

Owen, a native Shropshire lad, was machine gunned to death in France one week before the Armistice bells rang on November 11, 1918. He was twenty-five. Jarrell, born in Tennessee, was four years old when Owen died and the Great War ended. He enlisted in the Army Air Force in 1942 but failed to qualify as a pilot. Until the Second World War ended in 1945, 1st Lt. Jarrell served as a celestial navigation tower operator. (A job title he relished as the most poetic in the USAAF.)

No glory on the killing fields

Owen’s “Dulce Et Decorum Est” upends Horace’s line “It is sweet and proper to die for one’s country.” The Roman poet’s mythicizing of war is “the old Lie.” There was no glory in being corroded from within by clouds of chlorine gas. That “thick green light as under a green sea” dissolved the lungs that breathed it. And blinded eyes that watched it coming.

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs,

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots,

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of gas-shells dropping softly behind.Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime.—

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.In all my dreams before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

In an earlier version of the poem, these two lines “Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud/Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues” had been softer. The initial phrasing was less jarring, almost pretty: “And think how once his head was like a bud,/Fresh as a country rose, and keen, and young.” Owen rewrote those lines in witness to the appalling ugliness of death in battle. He turned his eye on the unbearable. And kept it there.

A body poised for dispersion

Published in 1945, “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner” is Jarrell’s most frequently anthologized work. A critical essay in the New York Times Book Review, called it “the ultimate war poem.”

From my mother’s sleep I fell into the State,

And I hunched in its belly till my wet fur froze.

Six miles from earth, loosed from its dream of life,

I woke to black flak and the nightmare fighters.

When I died they washed me out of the turret with a hose.

The brevity of it is as startling as the stark brutality of the image. The speaker describes his end in terms of an abortion. His is a life cut short. His flesh, shattered debris dispersed and hosed away. I was in high school when I first read it. That nightmare equation between abortion and the cruelty of combat has stayed with me ever since. After reading Jarrell it became impossible to imagine the killing of a fetus as anything but an act of war against a living body curled—”hunched”—in self-protection. No arguments, no moral philosophy, no rights discourse or appeals to choice have ever erased from the eye of my mind that single line: “When I died they washed me out of the turret with a hose.”

What else is there to know or say? Anything that might be left lies in the grip of tragedy. And beyond the reach of words.