Christmastide is over. Still with us, however, is Vatican preoccupation with youth culture and contemporary art. The showcased 2020 Nativity scene generated sneers and Mayday alarms. Demon-spotters went on high alert. Call the exorcist? By now, temperatures have gone down but the infection remains misdiagnosed. It matters that we get it right. Dislocated indignation distracts from real afflictions.

While this arts-and-crafts manger scene would have been unremarkable at Florence’s annual Mostra Internazionale dell’Artigianato, it was a sore thumb in St. Peter’s Square. Nevertheless, the apocalyptic censure called down on it is disproportionate to the thing itself. And more worrisome.

Catholic commentators rushed to light a rhetorical bonfire of the vanities. Prominent Italian art historian Vittorio Sgarbi warned us to shield our eyes: ” Don’t look at them. . . . These things have nothing to do with the Christian world. They are a caricature, a falsehood.” Taylor Marshall wondered, darkly, if the Nativity set was “evil”. Even Archbishop Viganò could not resist wielding it against Pope Francis and all his works. In a rousing impersonation of Savonarola, the archbishop roared that this “provocation of sick minds” is a “perfect symbol of the Bergoglian Church.”

No, Your Excellency, forgive me for demurring. But really, it was not. Grandiloquent denunciations, however stirring, obscure the point. It was Vatican fear of looking out-of-date, sharpened by enthusiasm for the the cult of Art, that brought this whimsical ensemble to St. Peter’s Square. Efforts to curry favor with adolescent sensibilities antedate the Bergoglian pontificate by more than thirty years.

Still Groovie After All These Years?

Creation of the 2020 Nativity set had been an ongoing project by students and faculty in F.A. Grue Art Institute, a high school of design in the Abruzzo, between 1965-75. The open-ended ensemble of life-size clay figures is a pitch-perfect relic of the circumstances of its making in the craft-craze decade. Selected by the Pontifical Council for Promoting the New Evangelization, the display incarnated Vatican reliance on entertainment value for securing the Church a fan base among millennials and their juniors. Pride-of-place in St. Peter’s Square signaled an anxious effort—strained to the point of absurdity—by the Vatican’s art-and-culture crowd to evangelize the young with pop-culture references. Passé ones, at that.

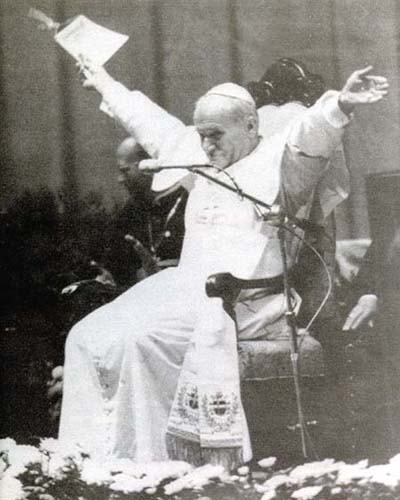

Strawberry Fields are not forever; tie-die wears out. No one lives in a yellow submarine except, perchance, certain Vatican prelates who want to score high on Snapchat. They need to let on that they know—or used to—what it is to be cool. Such is the hazard of youth ministries, a variety of niche marketing that has gripped Christian denominations for decades. John Paul II played the rock star at a youth rally-turned-rock-show in Madison Square Garden in 1979. Six years later, he initiated World Youth Day in Rome. In 2008 Benedict XVI expanded WYD into a massive five-day festival in Sydney, Australia.

Mass-cum-concert; tacky papal souvenirs (e.g. pope soap on a cord); root beer floats and nachos on the way to the Cross—in sum, a retrofitted Woodstock endorsed as the worship style for youth culture. (The chosen anthem for that event was Guy Sebastian’s gospel song “Receive the Power”, a title oddly suggestive of the iconic invocation familiar to attendees: “May the Force be with you”?)

One Last Quick Look

The idiosyncratic manger scene was never meant to serve as sacred art. It was a playful effort to depict the familiar tableau in contemporary Space Age terms. There is no sacrilege in that.

Who now remembers the exhilaration of the post-Sputnik years? Space exploration was in its infancy when this communal project began. The raw material for Star Wars, George Lucas’ space opera, was beginning to bubble. Modern airports were being built to accommodate the exciting new era of mass air travel. Enhanced air traffic control, overlapping radar networks, precision landing systems—these were novel communications wonders, the stuff of sci-fi. Families made outings to airports to watch planes land and take off. Human beings had landed on the moon!

Does the staging resemble a terminal of some kind? Nowadays, the Holy Family might well take a bus from Nazareth to Bethlehem. Or an indirect, unmarked flight into Egypt on Air Sinai. Either way, no more donkeys and camels. The astronaut? Twentieth century wise men with astral intuition traverse afar in spacesuits. And that ominous Darth Vader look-alike—what better signal of Herodian danger ahead for the newborn babe? The threatening figure is as legitimate an archetype of looming evil as any medieval depiction of a horned devil with a pitchfork tail.

Equally typical of its decade are the stuffs and style of the display. It emerged, like much else at the time, where Joni Mitchell would have serenaded it: in California. In 1962 the University of California, Davis, hired Robert Arneson to develop a ceramics program. In a nod to Picasso’s works in clay, he made humor and inventiveness the keynotes of a pedagogy created in conscious reaction to the pseudo-philosophical pretensions of Abstract Expressionism. Arneson’s ceramic strain of Pop Art traveled at the speed of a Simon & Garfunkel sound track from the Bay Area to the Adriatic. Its free-wheeling exuberance captivated a generation of young art students delighted to play with new materials and re-invent familiar forms. It found a particularly receptive audience in the Abruzzo town of Castelli, famous for its ceramics for centuries.

However off-beat the interpretation or craftsmanship, the Abruzzo portrayal is as innocent of blasphemy as a Lego Nativity. It is the departure from expectation—from the protocols of established iconography—that offends critics. Falsely accused of irreverence, its installation in St. Peter’s Square insinuates an intention that the project never held.

The figurines in St. Peter’s Square (a handful out of a total of 54) are bereft of irony, devoid of anything off-color, obscene, or derogatory toward the Nativity story. Viewed within the context of the Funk Art sensibility of its day, this ceramic outlier is blameless of the customary irreverence of its stylistic paternity. Virgin Mary is chastely robed. No Mary Quant mini dress or go-go boots bring her costume up to date. Her child is duly swaddled. An angelic pillar, hieratic and serene, stands guard over the assembly. A piping shepherd plays his traditional part.

Notice the goose in the right-hand corner of the first photo above. That, too, drew grumbles. Quite needlessly. Those student artigiani knew their own countryside. They knew the value of geese in an agrarian setting. Aggressive, territorial, and loud, the birds are familiar guards around Italian barnyards. Their honking warns off poachers; it alerts farmers, gardeners, and growers of every kind to the presence of a predator. That clay goose behind the Virgin is not a provocation—simply a watchful sentinel over a manger.

Agreed, Abruzzo’s Nativity was unsuited for solemn display in the Vatican. Both site and timing were malapropos. Nevertheless, all the artillery fired at it should have been aimed more accurately. A more consequential target is Vatican confusion between flattery and evangelization. When clerics of high standing submit to the compartmentalization of culture between generations—granting youth their own sovereign expression and applauding the contrast—they signal unease with adult consciousness.

That sad signal has consequences, none of them good.