Last month’s UNCuyo exhibition prompted the Social Ministry of the Archdiocese of Mendoza to whine that the art “seriously offends” religious convictions. That merely acknowledged the obvious. To offend was precisely what it had been designed to do. The display was created as a finger in the eye of Christians, Catholics in particular. Clearly, it required a response. But what kind?

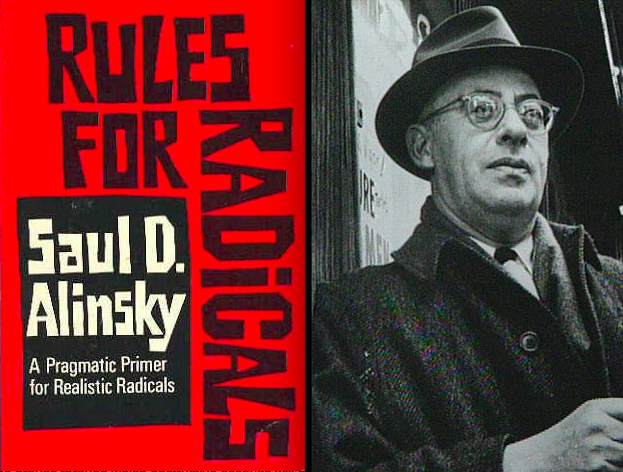

What counts is the character of the response. It is worth remembering that tone itself is a tactic. Enough, please, with politesse in the face of an implacable foe. Know when to abandon the Marquess of Queensbury’s objection to aiming below the belt. A skilled tactician, Saul Alinsky insisted that “Ridicule is man’s most potent weapon.” And: “A good tactic is one your people enjoy.” Both rules are useful in addressing hostile ideologues resistant to reason. They are still susceptible to sneers.

In preparation for an article on the UNCuyo affair, a writer for LifeSiteNews emailed me a list of questions. Would I please offer a few comments? Evidently my remarks did not suit because they were not used. The writer’s questions, though, are telling. They illustrate the reflexive temper of Catholic reaction to art intended to elicit outrage. Among them:

- As an artist, would you call this art? Why or why not? How would you define art?

- Would you say this is an attack on religion? [Obviously. Why ask?]

- Should art be allowed to mock religion in such an extreme way?

- Where is the line between art, which can often be shocking in order to evoke emotion or to grab the attention of the viewer, and something that is so offensive that it should not be done at all?

An irate censor lurks in those questions. But unless the state resurrects old blasphemy laws—a dangerous proposal—it gains us nothing to make an idol of our own disapproval. Hate speech, too, is a slippery notion. It works quite well in defense of Leftist barbarians conniving to silence our own side.

Howls of indignation are the anticipated, much desired response to transgressive art. It bolsters the significance of the offending work and, with it, its retail value. Nothing inaugurates a career better than publicity generated by moral outrage from the targeted audience.

So you ask: Well then, didn’t the archdiocese make the right call by standing with the transgressing artists? No. Not all. The “stand” was conciliatory—little more than a genuflection to incoherent thought-clichés about the status and production of art.

• • • • •

“But is it art?”

That is the default question of beholders faced with visual art that offends them. It is a reflexive commonplace driven by the inherited assumption that art is a timeless form—Art—that holds hands with Truth, Beauty, and Goodness. Exaggerated deference toward Art is a hallmark of social climbers of the intellectual sort.

Belief in Art—with a capital A—is a bequest from the Enlightenment. The work of artists’ hands is believed to hold a revelatory, even sacramental status. Jacques Barzun, in his 1973 Mellon Lectures, located the beginning of the Romantic ascent of art into Art in the eighteenth century. He described the budding philosophy of aesthetics this way: “The relation of art to beauty and to the ideal was evident. Art revealed the divine in man as nature revealed God.”

As popular reasoning goes, handiwork that is degrading, vile, trite, or risible cannot qualify as art in any accepted sense. Walter Scott reflected that faith when he wrote in his journal that veneration of the Old Masters is “a religion or it is nothing.” Given such conviction, can anything that trivializes the imagination or debases man’s creative spirit be called an artwork?

Short answer: Yes.

For economy’s sake, sidestep the metaphysical quicksand. Stay with the helpful reminder that art carries no warrant to improve or uplift the world. It can be put to any purpose, serve any master. Art can slay monsters or make saints of them. Conversely, it can slay saints as well. The art of a thing—is it good or bad art?—does not reside in subject matter but, like beauty, in the handling. And, to risk a much reviled assertion, in the eye of the beholder.

[The word “eye” is short-hand for that intricate medley of cultural preferences, acquired expectations, and individual sensitivities that color judgments. It is not to be disdained.]

• • • • •

If the archdiocesan press office had heeded Saul Alinsky, it might have sounded a different note:

Civility inhibits us from applauding mayhem in the rector’s office. At the same time, we cannot pretend to regret that the exhibition was cut short. It reflected poorly on the curricula and faculty of Mendoza’s premier institution. The display was banal, hackneyed, crude in conception and execution. It illustrated a deficit in those creative energies that the university is charged with fostering.

The university’s mission statement commits to “producing knowledge and forming people.” Yet the walls of the Rector’s office revealed the bankruptcy of the university’s stated mission. Visible to all beholders was the distance between administrative pretension and student achievement. Evidence of a pursuit of excellence was nowhere in sight. Bold action by a few beholders—however unsettling—rescued the fine arts department and social science faculties from visual testimony to their inadequacy as teachers and scholars.

The National University of Cuyo was founded to convey and augment Argentina’s cultural heritage, not to undo it by shallow means: travesty, parody, and clumsy pastiche. Yet that undoing is what the staging of #8M Visual Manifestos represented. After careful consideration, we believe that the demolition of the exhibit was an act of mercy toward the student body and the university’s public image.

Con oraciones a la Virgen del Carmen,

Archidiócesis de Mendoza

NOTE: Next, part 3— A Modest Proposal on the theme.