What we call culture war is a holy war. Sadly, clerical bureaucracy would rather lose it than make a fuss. Or so it appears from too many instances of clerical capture by the zeitgeist. Recent commotion over anti-Christian sentiment posing as feminist art on show in Mendoza, Argentina, illustrates the state of things. Justice Potter Stewart knew pornography when he saw it. Ordained shepherds of the archdiocese of Mendoza prefer not to notice. Art is all.

Back to that later. But first, some useful history.

The feminist art movement, a spawn of Second Wave Feminism, rose in tandem with the New Left in the 1960s. Shared loyalties shrank the transcendental dimension of Goethe’s Romantic “eternal feminine” to gynocentric fundamentalism. A descent into self-aggrandizing narcissism, it preached glorification of the female body as a sacred text. Encoded in women’s anatomy is an ancient wisdom, something sublime and essential that eclipses the idols of bourgeois religion.

The feminist art/goddess movement mimicked the Third Reich’s penchant for occultism. That earlier arcana grew from a desire to tap into Germany’s pagan roots to discover lost Aryan civilizations whose blood had not been tainted by mixing with outsiders and whose philosophical beliefs had not been watered down by Christianity. In like manner, feminist epistemology advanced the myth of lost matriarchies and celebrated a species of gnosticism: women’s ways of knowing.

Fast forward to 2023 and the National University of Cuyo, Argentina. Mendoza province’s largest institution of higher educations, it has a predominately female student body (with a ratio of 74 females to 26 males). UNCuyo celebrated this year’s International Women’s Day—March 8—with an exhibition entitled “#8M Visual Manifestos.” Without having to look, you knew by the word manifesto that here was an exercise in militant feminism preached at the level of pussy hats.

True to form, aspiring artist Cristina Pérez displayed a crucifixion guaranteed to raise hackles among—as one publication phrased it—”un grupo de fanáticos religiosos.” By now, a female Christ crucified is a shopworn schtick nearly five decades gone. To individualize an unoriginal conception, Pérez added a donkey’s head to the corpus.

In London, 1975, Edwina Sandys, granddaughter of Winston Churchill, created a plaster sculpture of Christ as a nude woman in a crucified position. Later cast in bronze, “Christa” hung behind the main altar of New York’s Cathedral of St. John the Devine in 1984 . “The Christa Project: Manifesting Divine Bodies” was back at the Cathedral for a six month viewing five years ago. For a half century so far, a naked female on a cross has emblematized the Gospel of Womyn’s Suffering.

A companion piece by an unidentified student showcased a vulva that mimicked the contour of traditional images of the Virgin Mary. Another stale gambit. In those early days of goddess studies, the Magnificat put a bull’s eye on Mary. “Be it done unto me according to thy word” violated the tenets of Helen Reddy’s 1972 pop canticle: “I am woman. Hear me roar.”

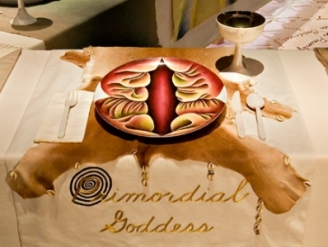

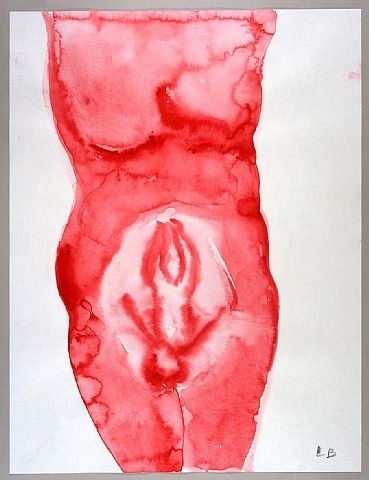

The art department at UNCuyo knows all this. Female genitalia has been a trade mark of the sacred feminine™ for some sixty years now. Louise Bourgeois’ many female torsos became sensations in the 1960s. Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party memorialized the box lunch in the late 1970s. Thirty nine schematized vulvas stylishly drawn on ceramic dinner plates edified susceptible women on the museum circuit on three continents. A high-art version of the beaver shot, the installation has been on permanent display in the Brooklyn Museum’s Sackler Center for Feminist Art since 2007.

Cristina Pérez dismissed critics of her work as “people who have not seen a TV program, or a show, people who have not gone out into the street, since today showing a nude does not imply that we all have to go out naked on the street, that is a very superficial reading.” Her entry hardly constitutes what is classically understood as a nude. Its raison d’etre is a cynical move to promote herself in the timeline of Bad Girls. Nudity here is quite beside the point. The irrelevancy of Pérez’s logic inhibits argument.

What to do?

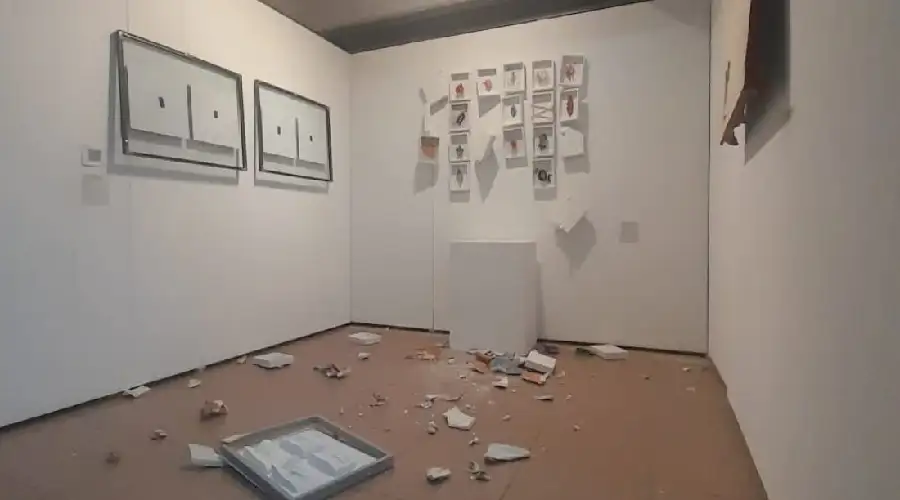

Students and faculty in various departments circulated petitions to withdraw the installation. Twenty people gathered in prayer at the installation. But it was hard to pray looking at the stuff. Direct action—mainly by men—was quicker and more efficient. They demolished what they recognized as symbolic violence against their own faith.

But not the Archdiocese of Mendoza. It wrung its hands and intoned:

We repudiate this act of physical violence towards the works exhibited there. We stand in solidarity with the artists who suffered damage to the fruit of their work and effort.

Solidarity with artsy zealots mocking history and Catholic theology! The toxic fruits of their labor! How accommodating. Sentimentalists will remember Art Garfunkel crooning “Bridge Over Troubled Waters.” More clear-eyed Catholics will hear an echo of the Stockholm Syndrome in this (the second) missive from the archdiocese. These are timid men who chose to identify with their abusers. Activist students and administrative organizers of a crude anti-Christian installation must be soothed, not confronted. It is a one-way non-aggression pact.

The exhibition was installed in the Rector’s office at UNCuyo. Rector Esther Sanchez, vice rector Gabriel Fidel, and other officers condemned “all kinds of violence” and urged dialogue. But the sine qua non of dialogue is mutual good will among parties. Yet none existed here. Archdiocesan castrati turned a blind eye to the fact that relevant authorities at UNCuyo had approved the display. ACI Prensa reported:

According to its organizers, the exhibition offers “a reflective look from art on patriarchal society.”

In addition, they assure that it seeks to contribute to the “deconstruction of stereotypes associated with women and the LGTBIQ+ community” (Lesbians, gays, transsexuals, bisexuals, intersex, queer and more).

In other words, the two feminoid entries were stalking horses for a broader campaign against traditional sexual norms. The archdiocese withdrew from the battle field with an incongruent appeal to “the protection of God, source of all reason and justice,” quoting the Argentine Constitution.

With hands folded on their chests, academic officialdom simulated piety: “The National University of Cuyo, with its plurality of ideas, visions, and thoughts offers its space for reflection. It calls for listening and accepting differences in peace.” Translated, that means overt expressions of malice by leftist ideologues are mere foibles in a reciprocal effort at comity.

When Church bureaucrats permit themselves to be so effortlessly mollified—their attention deflected—by duplicitous appeals to dialogue, they invite derision.