It is fitting that Thanksgiving should fall in the month of the Holy Souls. November, of course, marks the anniversary of the Pilgrim landing. But more than that, it memorializes the lives—and deaths—of those who were instruments in forging the religious and cultural lineaments of our nation.

A day to commemorate simply a life-sustaining harvest might readily have been set on or close to the autumn equinox. That would have followed ancient precedent honoring the divinities of harvest time, guardians of the threshing floor. Ceres and Demeter shared claim to the season with agrarian societies down the ages. (The Irish celebrated Lughasa, a festival dedicated to Lugh, the Celtic god of light who left his name on the city of Leiden, from which the Puritan Separatists began their trans-Atlantic saga.) Man has been a celebrant of the vital force of crops in their seasons since the infancy of agriculture.

By a stroke of serendipity, our own Thanksgiving inhabits the month that begins for Catholics with the Feast of All Saints and All Souls Day. A certain symmetry honors the date of our national feast of gratitude. The rightness of its timing moves me more each year.

A September date would have provided a felicitous affinity with Sukkot, the eight-day Feast of Tabernacles. By Torah times, Leviticus had set the already venerable festival in September to commemorate God’s provision for the Jews during their forty years of wandering in the desert. The Gospel According to John tells us that Jesus himself celebrated Sukkot:

On the last and greatest day of the festival, Jesus stood and said in a loud voice, “If anyone thirsts, let him come to Me and drink. He who believes in Me, as the Scripture has said, out of his heart will flow rivers of living water.” (John 7:37-39)

But the first Thanksgiving was celebrated by Protestants. Sukkot was not on their minds. Neither was the Feast of All Souls, a devotion with roots stretching past the Middle Ages back to the Second Book of Maccabees:

Turning to supplication, they prayed that the sinful deed might be fully blotted out… Thus made atonement for the dead that they might be free from sin. [2 Maccabees, 12:26 and 12:32.]

It is that association of November with the dead that touches me when I read of the Pilgrims. This intrepid vanguard had risked “a vast ocean and a sea of troubles”—William Bradford’s words—when they “committed themselves to the will of God and resolved to proscede.” So many died in the effort.

By the time they finally left England on September 6, 1620, they had been living onboard the May-Floure and her sister ship the Speedwell for nearly a month and half. The two were to have traveled together but, 300 miles out to sea, the Speedwell began to leak and proved unseaworthy. Both ships returned to Plymouth, England, where the Speedwell’s passengers and cargo were crowded onto the already full May-Floure. Alone this time, the 100-foot ship set sail again with 102 wearied passengers plus 30-40 crew.

The debilitating conditions of passage took their toll. In October, fierce westerly winds struck at the ship, assaulting timbers and forcing sea water through the caulking. Passengers lived in constant wet, damp even in their berths. Suffering inadequate rations and lack of sanitation, many were sick before Cape Cod was sighted on November 9th. The ship pressed southward to the Virginia Colony, which extended then into today’s New York State

Two days later, frustrated by gales and currents from reaching the Hudson River as planned, the ship turned north again. It set anchor where it could, in what is now Provincetown Harbor. Homeless in a cruel climate on an alien landscape, already weakened by scurvy and ship-board infections, the assembly suffered hunger and exposure as well. Within the first year fifty-one died, some within weeks of landing. Only four of the eighteen adult women who made the voyage survived to the first Thanksgiving. By then, many children had been orphaned. The wonder is not they died in great numbers after arrival but that half of them survived the winter of 1620-21 at all.

Bradford’s History describes the desolation that greeted the settlers:

They had now no friends to wellcome them, nor inns to entertaine or refresh their weatherbeaten bodys, no houses or much less towns to repaire too, to seeke for succoure. . . .

And for the season it was winter, and they that know the winters of that cuntrie know them to be sharp and violent, and subject to cruell and fierce stormes, deangerous to travill to known places, much more to search an unknown coast. Besides what could they see but a hideous and desolate wildernes, full of wild beasts and willd men? And what multituds ther might be of them they knew not.

In Bradford’s telling—contrary to our school book versions—the “willd men” were not initially pleased to see them. He wrote: “These savage barbarians, when they mette with them (as after will appeare) were readier to fill their sids full of arrows than otherwise.”

Death was the Pilgrims’ constant companion; mortality, an abiding tutor. More intimate with transience than we are, men of the seventeenth century drew courage from the transcendent truth inherent in recognition of—and a certain detachment from—the fragility of our place in time. Robert Cushman, an important organizer of the Mayflower expedition, used these words in his “Reasons and considerations touching the lawfulness of removing out of England into the parts of America:”

But now we are in all places strangers and pilgrims, travelers and sojourners, most properly, having no dwelling but in this earthen tabernacle; our dwelling is but a wandering, and our abiding but as a fleeting, and in a word our home is nowhere, but in the heavens.

God grant us the wit and grace to stand worthy of the faithful men and women who raised up a nation for us.

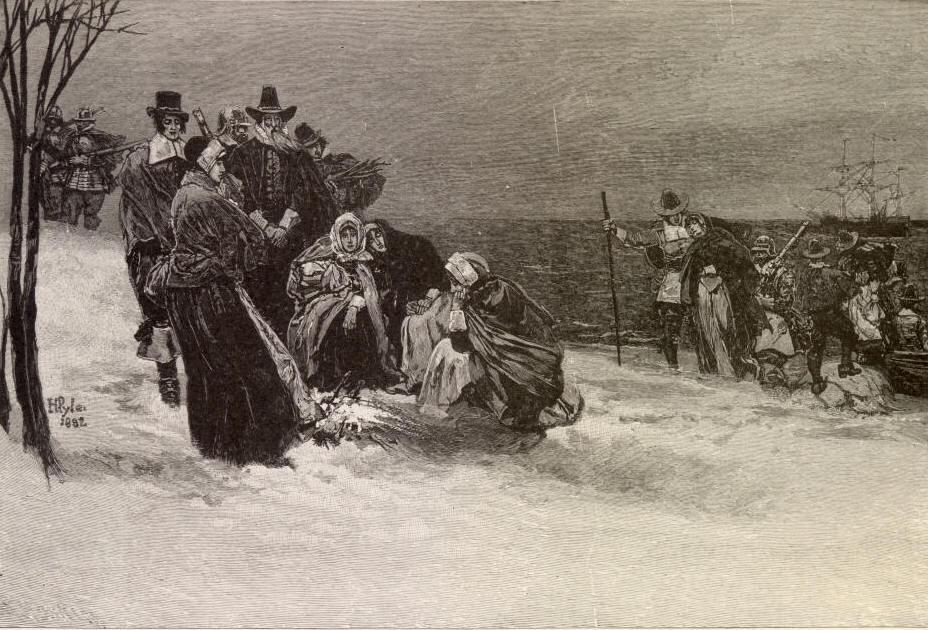

Note: The illustration above is Howard Pyle’s Landing of the Pilgrims (1882).