What is beauty ? The question is better left to philosophers. It is a bootless one for artists to brood over. It does nothing to enhance the work of an artist’s hand.

It is the experience of beauty—sensory, emotional, psychological—not any definition that makes an artist’s work intelligible to himself. Herself. Creators of the greatest beauty possess it by instinct. Yet, the question has become a species of branding device among Christian, particularly Catholic, artists. It is the asking that matters more than the answer.

The ultimate, if cloaked, purpose of the question is to indicate a well-stocked mind. It leads inescapably to references—carried casually like a vintage purse—to what the Scholastics understood as an attribute of God. Curtsying to beauty’s acquired status as a transcendental has become a credential, a certificate, in its way, of one’s Thomist pedigree. No small degree of intellectual vanity inhabits the inquiry. It offers itself as evidence that artists, too, can get past the goalie in the gray cell department.

But once there, what then? Sensuous beauty as a herald of moral beauty, followed by the equivalence of moral beauty with goodness, takes us past Augustine, past Cicero and the Stoics, back to Aristotle’s Rhetoric. (“The beautiful is that which is desirable for its own sake, and pleasant, or that which, being good, is pleasurable because it is good.”)

The Good—so pure, simple in upper case; messy and misleading in lower. Whose good? (Catch the golden showers scene in Stephen Frears’s My Beautiful Laundrette, a benchmark in the pantheon of queer cinema, before you answer.) The Ethical Fallacy—good men build good buildings, et cetera—lurks below the surface of much Christian discussion of beauty in the arts.

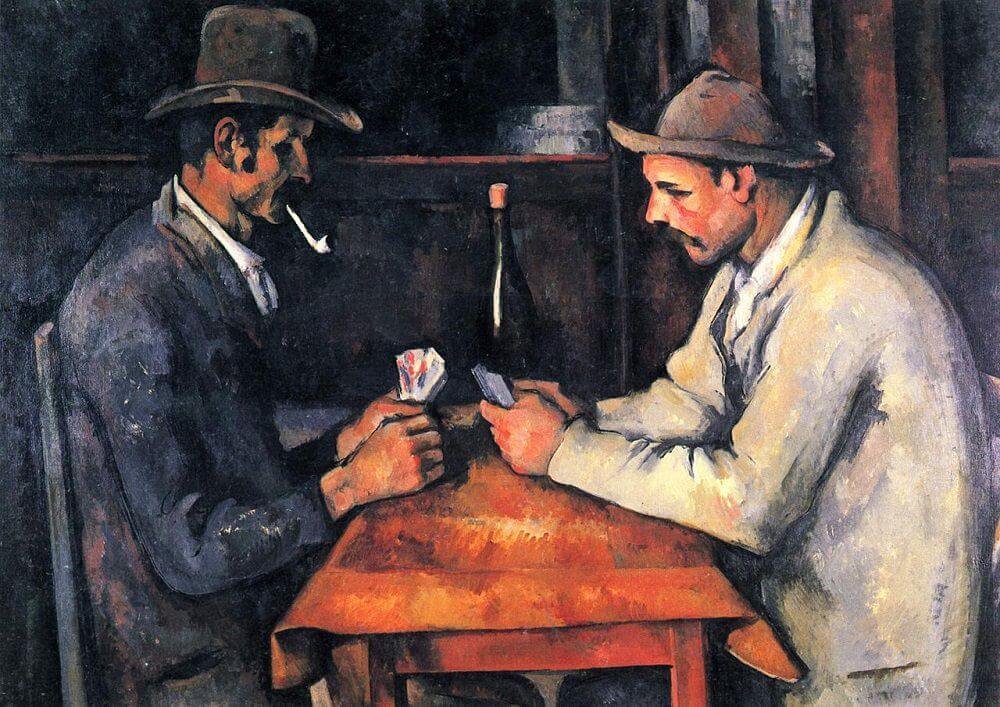

What is beauty? When I hear the question, my mind goes straight to Cézanne for two reasons. The first might sound silly but I do not mind: Imagine a card game where one of the players cannot make a move until he rises to reflect—out loud, eyes off his cards—on the meaning of chance.

Sit down, Jack. Keep quiet and play your hand.

My second reason is more sober. Though Cézanne was a believing Catholic, his greatness as a painter had nothing to do with his faith. Deduction can coax no hint of his Catholicism out of his painting. (John Rewald cites 1891 as the year Cézanne, in his early fifties, embraced his natal tradition and turned devout.) In his work, Cézanne built upon his precedents, not metaphysical musings.

And despite his brilliance as a painter, his Catholicism put him on the wrong—reactionary—side of the Dreyfus affair. (His allegiance to the largely Catholic anti-Dreyfusards cost him his life-long friendship with Émile Zola.)

And despite his brilliance as a painter, his Catholicism put him on the wrong—reactionary—side of the Dreyfus affair. (His allegiance to the largely Catholic anti-Dreyfusards cost him his life-long friendship with Émile Zola.)Gregory Wolfe, founder and publisher of Image Journal , recently gave the inaugural lecture to the newly formed Catholic Artists Society. He spoke eloquently on behalf of the freedom of the arts despite his own felt constraints in speaking under the auspices of the Thomistic Institute. The talk he gave was very good. The talk he really wanted to give would have been even better. The one he strained at the bit to deliver was epitomized in the anecdote he related about Flannery O’Connor. As Wolfe tells it, O’Connor, on the stump as a writer, suffered the usual question from a member of the audience: “Why do you write?” Without a second’s hesitation, O’Connor shot back: “Because I am good at it.”

Wonderful! O’Connor’s reply assents, in spirit, to Dorothy Sayers’ insistence that the only Christian art is good art. Both observations should be tacked to artists’ studio walls. Certainly, the particular awareness and challenges of novelists are different from those of visual artists. So, too, is the nature of their materials—words. Nevertheless, both O’Connor and Sayers grasped that at the heart of any artistic endeavor is talent and commitment to craft. For the Christian, that implies the humility to view clearly the character and dimensions of one’s own gift.

Acknowledgment is ensnared in a thousand seductions. Humility is hard to acquire and rocky to sustain in any life. It becomes all the harder for artists when voices within the Church, the very guardian of that virtue, insist on flattering them as keepers of a special kind of metaphysics.

Note: I had identified My Beautiful Laundrette as a Wim Wenders film. Not so. It was directed by Stephen Frears. All fixed above.